Object of Intrigue: Two-Wheeled Transport for Regency Dandies

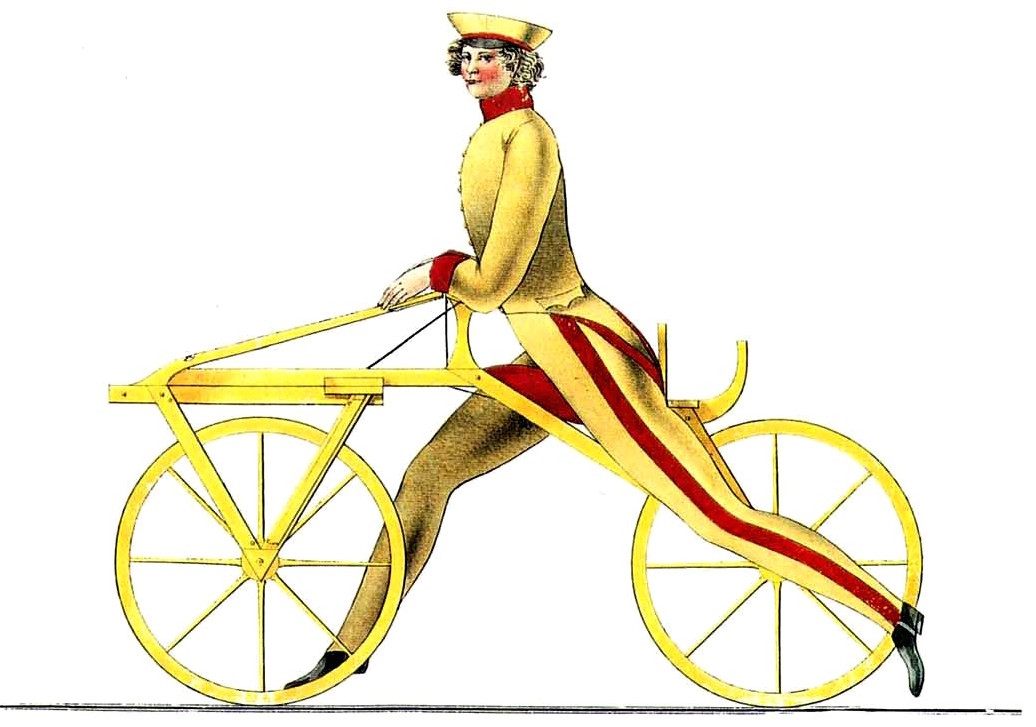

Regency dandies drag-racing their draisines at the Jardin du Luxembourg in 1818. (Image: Wikipedia/Public domain)

This holiday season, millennials will be unwrapping futuristic-looking hoverboards, taking to the sidewalks, and incurring a mix of confusion, awe, and ire from people over the age of 30.

These sentiments echo those expressed almost 200 years ago, when another contentious youth-focused form of two-wheeled transport was introduced: the Laufmaschine. It was the first human-powered, two-wheeled transport device; it pre-dated the penny-farthing, a type of early bicycle, by more than 50 years.

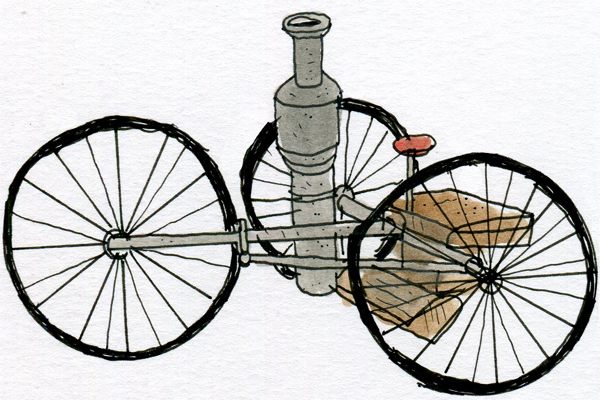

Also known as the swift walker, the pedestrian hobby horse, the draisine, and the first velocipede, the Laufmaschine (“running machine”) was invented by German forester Karl Drais in 1817. It consisted of a pair of equally sized wheels topped with a wooden beam, which held the whole thing together. A leather saddle on the beam gave the rider a place to sit and a tiller-style steering post gave control over the direction of the front wheel.

There were no pedals—the rider would sit astride the Laufmaschine, let their feet touch the ground, and take long strides to get moving. To stop, riders dragged their legs along the ground.

A drawing from Drais’ three-page pamphlet on his 1817 invention. (Image: Wikipedia/Public domain)

Patented in France in 1818, Laufmaschines “soon became status symbols among young noblemen,” wrote Tony Hadland and Hans-Erhard Lessing in Bicycle Design: An Illustrated History. The contraptions were priced above the means of the working class, leading them to become a toy for pleasure-seeking dandies—hence another one of the velocipede’s nicknames: the “Dandy Horse.”

London caricaturists had a fine time lampooning these cravat-wearing sidewalk menaces who trotted along on their running machines. The riders faced a “storm of ridicule,” according to an 1883 edition of cycling magazine The Wheelman. “Nothing could well have looked more absurd than a gentleman, exquisitely dressed in the fashion of the times, going along the muddy streets in this guise,” it noted.

A draisine at the Kurpfälzisches Museum in Heidelberg, Germany. (Photo: Gun Powder Ma/Wikipedia)

In the dying days of 1818, London carriage maker Denis Johnson released an improved version of the draisine, which he termed the “pedestrian curricle.” It had larger wheels, a simpler steering mechanism, a lighter overall weight of 40 to 50 pounds, and an adjustable seat.

Convinced of the mass appeal of this modified Laufmaschine, Johnson opened a riding school in Covent Garden. There he taught fashionable young men how to cruise along on his curricles, and custom made the contraptions for each buyer, taking their weight and inseam into account to create the most comfortable ride possible.

It wasn’t just men who got to go on velocipede joy rides—in 1819, Johnson debuted a version of the pedestrian curricle with a step-through frame, specially designed for ladies’ comfort and modesty. By this time, however, the draisine fad had already peaked.

The lady version of the pedestrian curricle had a step-through frame. (Photo: Ian.wilkes/Wikipedia)

Velocipedes made it to the United States by 1819, but their popularity was modest. About 100 of the machines circulated in the country, which was enough to warrant the establishment of riding rinks in the east. Those who couldn’t afford to purchase a two-wheeler outright could rent them.

“Riding downhill at high speed was a particularly enjoyable activity,” notes the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, which holds a draisine from around 1818 in its collection.

By 1820, the Laufmaschine fad was over in both Europe and the U.S., having incurred the ire of pedestrians protective of their sidewalk space. Another issue leading to its demise was the fact that the draisine caused occasional rearrangement of riders’ internal organs. “The defects of the velocipede, its rigidity, and the strain on the rider in propelling it by muscular thrust, besides rendering it impracticable for general road travel and subjecting the rider to a severe jolting, were a frequent cause of abdominal hernia,” noted The American Cyclopaedia.

On the bright side, draisines did not have a tendency to burst into flames.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook