Objects of Intrigue: Einstein’s Brain

OBJECTS OF INTRIGUE is our feature highlighting extraordinary objects from the world’s great museums, private collections, historic libraries, and overlooked archives.

EINSTEIN’S BRAIN

The iconoclast genius’ grey matter, harvested against his wishes, a bit worse for wear

Donated in 1955

Mutter Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

There are many collections of brains in pathological and medical research collections around the world, from the tumor-infested samples at Yale’s Cushing Collection to the Brain Museum in Lima, Peru. But while most brains on display function as educational examples of some kind of medical curiosity or horrifying disease, the Mutter Museum has a rare example of a brain curated not because of its defects, but because of its extraordinary brilliance.

Bess Lovejoy, enthusiastic stalker of oddities and the author of the upcoming book Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses told us more about the famous brain:

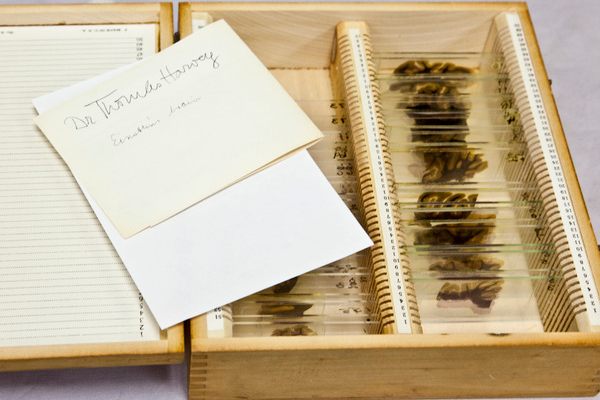

They look like strands of kelp, shards of bark, or the shadows of small animals in distress. In fact, these slides contain slivers from the brain of the twentieth century’s most famous scientist: Albert Einstein.

Einstein probably wouldn’t have been pleased. He wanted to be cremated, and for the most, he part got his wish. (His ashes were scattered in a secret spot on the Delaware River). However, the pathologist on duty the night Einstein died in Princeton, New Jersey, wanted to keep the great physicist’s brain away from the flames, so that others might one day study it for clues to his genius.

The pathologist, Thomas Harvey, ended up embroiled in drama with Einstein’s family and executor, not to mention the hospital, but was eventually allowed to keep the brain as long as he used it only for scientific study (no tourist attractions allowed). At first, scientists who analyzed small sections of the gray matter saw nothing unusual, but by the 1980s, some began to find intriguing features in areas involved in visual, mathematical, and spatial processing. It turns out that Einstein’s Sylvian fissure (a prominent groove) was shorter than average, while his parietal lobes were slightly wider, and his left inferior parietal lobe richer in glial cells (which nourish neurons). Neuroscientists have theorized that this architecture may have allowed Einstein to think with the kind of “associative play” of images that he claimed was key to his discoveries.

However, the typology of Einstein’s brain can never completely account for his brilliance, in part because we don’t know what came first: was Einstein a genius because his brain looked this way, or did it look this way because he was a genius? It’s hard to know, especially without a lot of other Einstein-quality brains available. Meanwhile, this brain—a victim of 1950s-era preservation techniques and Harvey’s many journeys around the country—is no longer in great shape for study.

The Mutter’s forty-six microscope slides of the brain come from a Philadelphia neuropathologist named Lucy Rorke-Adams, who donated them to the museum in 2011. She received them from a colleague in the 70s, who got them from Harvey himself. An octogenarian herself, Rorke-Adams said she wanted to find a safe place for the slides before she passed on. She chose well, and the slides are now one of the museum’s most prized possessions.

Bess Lovejoy is a writer, researcher, and editor based in Seattle. She writes about dead people, forgotten history, and art, literature, and science. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Believer, The Boston Globe, The Stranger, and other publications. She also worked on the Schott’s Almanac series of books for five years. Her own book, Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses, comes out March 2013 from Simon & Schuster.

Image of Einstein’s Brain courtesy of the Mutter Museum, used with permission.

SEE IT FOR YOURSELF: MUTTER MUSEUM, Atlas Obscura

Einstein’s brain is on exhibit at the Mutter Museum, located on the museum’s main level, near the portrait of Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter.

19 South 22nd Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103

Open: Open daily, 10am to 5pm

OBJECTS OF INTRIGUE is our fortnightly feature highlighting extraordinary objects from the world’s great museums, private collections, historic libraries, and overlooked archives. See more incredible objects here>

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook