Indigenous Cuisine Is Being Served in the Back of a Berkeley Bookstore

Café Ohlone features traditional recipes and foraged ingredients.

When Europeans first arrived in California, they met Native Americans who enjoyed one of the most varied diets in the Americas. The staples of corn, beans, and squash had never crossed the deserts from Mexico and the inland Southwest, but other edible plants flourished in the mild coastal climate. A dense network of tribes lived on acorns, piñon nuts, wild vegetables, seafood, and game.

The Spanish almost immediately set out to destroy this way of life. They forced the Native Americans of California to labor on missions, farms, and ranches, and made them dependent on European crops. Thanks to superior weaponry and the diseases that ravaged the indigenous population, they were successful in eroding the connection of native peoples to their lands and foods. This created a bitter legacy, one where even recently, native Californians who practiced their old traditions and religions were labeled as backward.

Today, there is only one place in California serving the cuisine of these peoples, and it’s not in a national park café or a tribal casino restaurant. Behind a bookstore in Berkeley, surrounded by the city that covered their forest and grasslands, members of the Ohlone people offer a taste of an enduring culture.

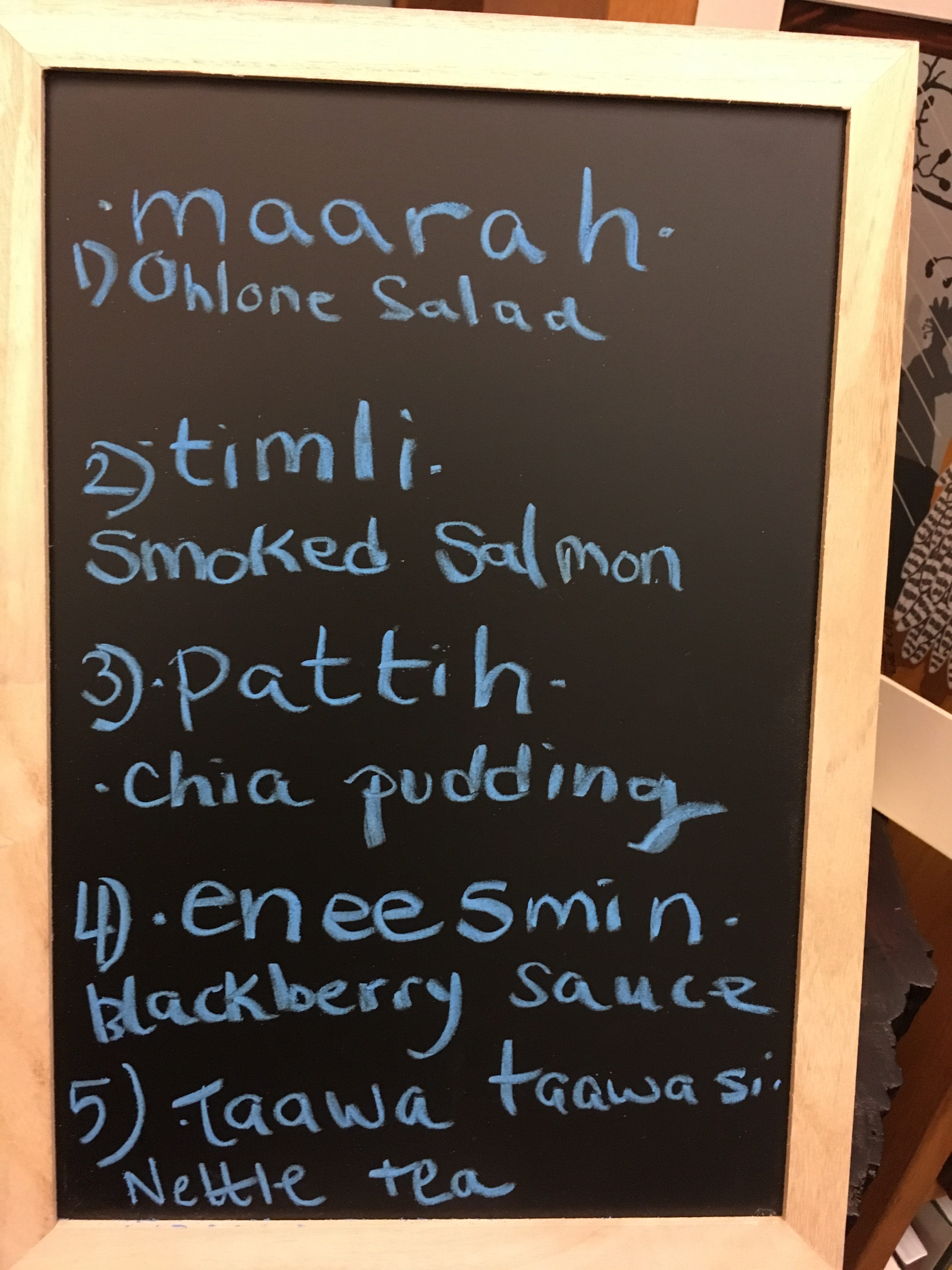

This culinary project has two names: Café Ohlone in English, and mak-’amham, which means “our food” in Chochenyo Ohlone. It’s the brainchild of partners Vincent Medina, a member of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, whose traditional lands span the East and South Bay, and Louis Trevino of the Rumsen Ohlone from the Carmel Valley. The two met in 2014 at a conference on native languages and bonded while listening to old oral histories of their people recorded by anthropologists. Many of the narratives were reminiscences of traditional gathering and cooking practices.

As they listened, the two men became curious about Ohlone food. “In the 1920s and 1930s, our ancestors talked about where to gather these foods, the recipes for them, how much they loved them and missed eating them,” says Medina. They started going to wild spaces to gather the ingredients described on the century-old recordings in order to recreate the old recipes. The results were successful: enough so that they decided to make Ohlone food the centerpiece of a project combining education with dining. In September 2018, Medina and Trevino held Café Ohlone’s first lunch in a space behind Berkeley’s University Press Books, an academic bookstore. Now, it’s a weekly event.

Medina starts every lunch with a welcome and a prayer in his people’s Chochenyo language. Trevino adds commentary and anecdotes over the course of the meal. Before anything is served, the two introduce the day’s ingredients and their origins. The introduction combines grim history, gentle humor, and solemn ritual, including setting aside a plate for the ancestors. “We want our ancestors to be at the table with us, because we believe that they are guiding our work,” Medina says.

One recent meal included a salad of watercress mixed with sorrel leaves, blackberries, gooseberries, and popped amaranth seeds, all gathered from nature around the Bay Area. The cress has a mildly peppery herbal flavor that mixes well with the citrusy sorrel and tart berries, and the amaranth adds a satisfying crunch and slight nuttiness. The salad was topped with roasted hazelnuts finished with salt gathered from tidal pools, along with a subtle walnut oil and bay laurel dressing.

Ohlone cuisine uses berries and sumac for tart and sour flavors, along with a variety of savory vegetables, seeds, and herbs. Their seasonings don’t include anything like the fiery chili sauces of the desert Southwest. Instead, their traditional culinary aesthetic accents natural flavors. This was evident in the salmon, flavored only with salt and an agave rub before being smoked and baked. Maidu tribe members caught the meal’s fish north of the Bay Area. While the same species once teemed in Bay Area waters, now most are too polluted by shipping, industrial activity, and street runoff. Traditionally, Ohlone cooks staked the fish next to smoky fires or slow-cooked them in underground ovens, but Café Ohlone uses modern techniques to create the same rich flavor.

The chia chocolate pudding was a blend of flavors from Central and North America. Chia seeds are high in protein and were a traditional snack for Ohlone message runners who needed a lot of energy. Their crunch added texture to the chocolate pudding lightly sweetened with agave. All of the dishes are offered on one plate, as dividing meals into courses is not a native concept. A blackberry and bay laurel sauce that was served as a complement to the dessert had tart herbal notes that were also a fine counterpoint to the oily, smoky fish.

To drink, diners were offered stinging nettle tea, with lemon added to balance the earthy, grassy flavor of the herb. Raw nettles cause blisters on skin contact, but heat neutralizes the irritants, leaving behind a mild tea with anti-inflammatory and diuretic properties. Like many other items served at the meal, it put an unfamiliar ingredient into an approachable context. Meals at Café Ohlone don’t involve flashy innovations or novelties. Instead, Medina and Trevino want to honor the ingredients and techniques of their ancestors, while introducing them to a wider audience. “Twenty years ago, only a handful of these foods were eaten by our tribal members, but today they are on our dinner tables on a regular basis,” says Medina.

While the food is the focal point, after the meal guests are invited to hear songs in Ohlone languages and learn a traditional game of chance played with shells, using sticks as counters. The two-hour window allotted for the event passes quickly. A visit to Café Ohlone is a cultural introduction to the original denizens of the Bay Area, and one that’s been a long time coming. As Medina noted in closing remarks, “We hope that through eating our food, hearing our language, playing our games, you will be motivated to stand up for our community away from this table.”

Café Ohlone is also experimenting with their outreach. They host lunches every Thursday and dinners most Saturdays, along with a Sunday brunch featuring acorn flour pancakes and duck-egg frittatas. The duo recently hired a tribal member to assist with events, but they don’t plan to make the café a daily operation because both are deeply involved in other projects. These include teaching both language skills and cooking to other tribal members, as well as campaigning for state recognition of Ohlone historical sites. Instead, the cafe’s schedule is on their website, and they prefer that guests make reservations in advance.

The few dozen people a week who go to Café Ohlone both sample local flavors while learning about the people who quietly kept their traditions alive for centuries. As they leave, they might momentarily imagine what this landscape was like when the bay could be seen through the trees, and when more deer roamed than students and commuters.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook