The Fixers Who Buried Old Hollywood’s Biggest Scandals

When stars needed something to be swept under the rug, they summoned these guys.

Howard Strickling’s phone was always ringing. First it might be Jean Harlow, panicking that William Powell had gotten her pregnant. Then it might be a security guard, informing him that he’d removed a belligerent Spencer Tracy from yet another bar. Once it was Marlene Dietrich, distraught after discovering John Gilbert’s dead body.

As the head of publicity for MGM, Strickling “handled” all these potentially scandalous affairs for the studio’s stars. From the 1930s through the 1960s, he worked with MGM general manager Eddie Mannix to maintain the carefully curated images MGM had built for each of its movie stars. That meant keeping damaging stories out of the press—or, if it was too late, making those stories disappear.

Mannix and Strickling were an unlikely team. Mannix, a thug who hung out with mobsters, first caught the eye of film-executive brothers Nick and Joseph Schenck while working construction at their amusement park in Fort Lee, New Jersey. (Josh Brolin plays a loose version of him in Hail, Caesar!) Strickling was a “dapper former journalist” who transitioned over to MGM publicity in 1919. But together, they quashed almost every type of tabloid item imaginable, as detailed in The Fixers by E.J. Fleming.

When Harlow, Judy Garland, Lana Turner, and countless other MGM actresses found themselves pregnant out of wedlock, the two men procured hasty abortions. (They covered up the visits with false names and even false ailments. Jeanette MacDonald had an “ear infection.”) Well aware of Tracy’s alcoholism, Strickling assigned an entire “Tracy Squad” ambulance team consisting of a driver, a doctor, and four “attendants” who were really security guards.

When “difficult” stars refused the help of Strickling and/or Mannix, the fixers had no qualms about throwing them under the bus. After closeted actor Nils Asther refused to keep up his sham marriage to vaudeville actress Vivian Duncan any longer, Strickling greenlit a 1933 article in Screenland Magazine that questioned why Asther did not live with his wife and child—and heavily implied the problem was not dalliances with other women. Asther was fired soon afterwards.

But perhaps the wildest example of the studio fixers’ intricate work was Loretta Young’s curious “adoption” of her biological daughter Judy Lewis.

Young became pregnant by her costar Clark Gable in 1935, while they were shooting The Call of the Wild. At the time he was married to his second of five wives, Maria Langham, and according to Young’s daughter-in-law, the sexual encounter was not consensual.

Young was Catholic and refused to have an abortion, so Strickling sent her into hiding. He first told the press she was on vacation, then simply ill, but when she missed her sister’s wedding, reporters went into a frenzy of speculation. So he arranged for an interview between his friend, a journalist at Photoplay, and Young, who was nearly nine months pregnant. Young remained in a bed piled high with strategically placed pillows and blankets for the entire conversation. A studio nurse was sent in several times to replace a prop intravenous bottle.

After Young gave birth to her daughter, the system went into high-gear. The baby girl stayed at a bungalow in Venice Beach for several months, and was then placed in an orphanage. Over a year later, Young announced that she planned to adopt two orphan children. But in a surprise turn of events, she explained, the biological mother came to claim the totally nonexistent second baby. So she simply wound up with Judy, her actual biological child. The MGM fixers helped her plan every step of this elaborate story, which Young stuck by publicly throughout her lifetime. She only confirmed the truth to her daughter in 1966, and to the world in her 2000 posthumously published autobiography.

Throughout this complicated case, Strickling and Mannix were following Young’s express wishes. Technically, they were working in her best interest. But the two fixers also committed horrific transgressions against women to protect the studio, and nowhere is that more apparent than with Patricia Douglas.

Patricia Douglas was not a name like Loretta Young, and that’s the way she wanted it. The young dancer ended up in Hollywood only because her mother harbored dreams of designing movie costumes. As David Stenn wrote in Vanity Fair, “she did not drink, date, or dream of film fame.” But she had appeared in musicals for Warner Brothers and Columbia Pictures, which is how she came across an MGM casting call in 1937. While she believed it was for another dancing role in a movie, it was actually for a party.

The party was part of a five-day sales convention to celebrate MGM’s big year. This particular bash, according to the convention schedule obtained by Vanity Fair, was a “stag affair, out in the wild and woolly West where ‘men are men.’” The men had, at this point, been drinking for three days straight. After Douglas arrived at the studio-owned “ranch” with 120 other dancers in short cowgirl outfits, she slowly realized she’d been bused over as a plaything for drunk, lecherous businessmen. One of them was especially interested in her.

Douglas found David Ross creepy from the start, and tried to dodge him by escaping to the ladies’ room. But when she reentered the party, he and another man, by her recollection, held her down and poured liquor down her throat. She broke free to throw up in the bathroom and stumble outside for fresh air. It was there that Ross found her, dragged her to his car, and raped her.

Douglas was taken to the hospital and examined by a doctor practically owned by MGM. None of the cops at the party bothered to file a criminal report. Undeterred, she filed a complaint against Ross with the Los Angeles district attorney’s office and took her story to the press. Mannix, who had been at the party, leapt to defend MGM. He systematically strong-armed potential witnesses into slandering Douglas. She was painted as a lying lush, despite the fact that she never drank. Some who had previously given statements supporting her claims would not repeat them in court. Her criminal case failed, and MGM also succeeded in stalling her civil suit (which named Mannix). She tried one more time, only for her own lawyer to betray her. There was no other recourse, and her story was effectively erased for decades.

When later asked about Douglas, Mannix supposedly joked, “We had her killed.”

Strickling and Mannix’s fixer days ended in the 1960s. Strickling retired in 1969 and Mannix died in 1963, as the studio system was already heading towards collapse. No true successor rose to take their place, since traditional fixers made little sense outside a traditional studio system, where actors are owned and beholden to morality clauses. But Fred Otash might be considered the imperfect heir to Strickling and Mannix’s shady empire.

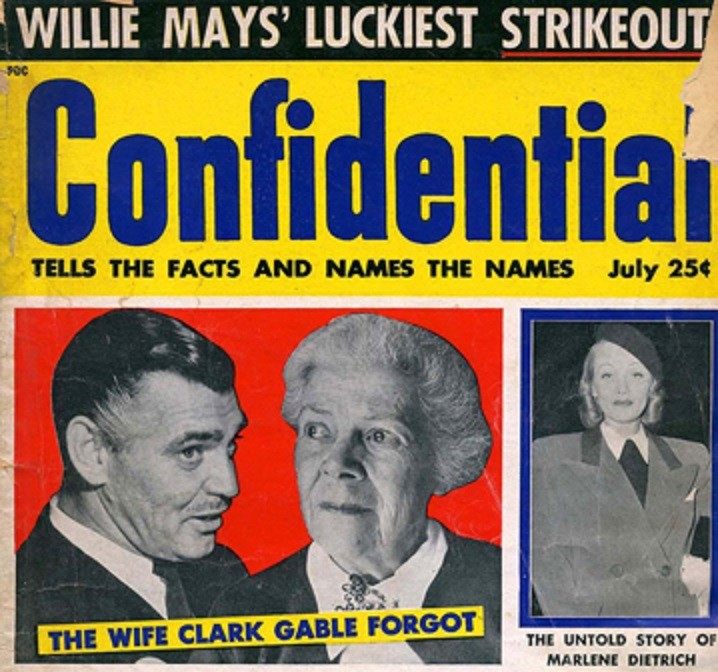

Otash was a former LAPD cop turned private investigator who took on celebrity clients including Peter Lawford, Errol Flynn, Bette Davis, and Judy Garland. Sometimes he spied on people to help his clients with messy personal affairs. Other times he provided security. (Garland’s ex-husband recalls Otash guarding her home.) But Otash played both sides. As a freelancer for the sleazy tabloid Confidential, he helped to out several closeted stars and spread other damaging dirt.

Due to Otash’s reputation, his sensational stories were often questioned—sometimes by the man himself. Although Otash told associates he rushed to Lana Turner’s home the night her boyfriend Johnny Stompanato was stabbed by her daughter Cheryl Crane, and even removed the knife from the body, Otash dismissed the story in a 1991 interview. “Beverly Hills police chief Clinton Anderson once accused me of removing the knife from Stompanato’s body, wiping off Lana Turner’s fingerprints, putting on Cheryl Crane’s fingerprints and then shoving the knife back into the body,” he said. “Crazy.”

So much of Strickling, Mannix, and Otash’s work is bound up in contradictory reports and rumor. But if their confirmed deeds are any indication, it was the fixers—not the filmmakers—who concocted the most twisted tales in old Hollywood.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook