Miss La La Soared Through Europe as the Victorian Era’s Best-Known Aerialist

As a Black woman, the daring circus performer also confronted the racial politics of the times.

For Women’s History Month, Atlas Obscura is living on the edge with Women of Extremes, our series dedicated to those who dared to defy expectations and explore the unknown.

The domed roof is high above, its dark windows looking out onto the Parisian night. The audience, presumably, is seated far, far below, their necks craned upwards, their faces frozen in masks of awe. Suspended in between, the center of all attention, is a Black woman hanging from a rope by her teeth. Outfitted in white and gold, this iron-jawed woman, Miss La La, is the star of the Cirque Fernando. And this trick–which few others can perform–is her pièce de résistance.

So impressive was the feat that French impressionist Edgar Degas sought to capture the scene in his 1879 painting “Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando.” Art critic Roy McMullen reportedly hailed the oil painting, on display at the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in Paris, as “Among the artist’s most striking and complex achievements.” But what of the woman herself? Who was the aerial artist at the center of the art?

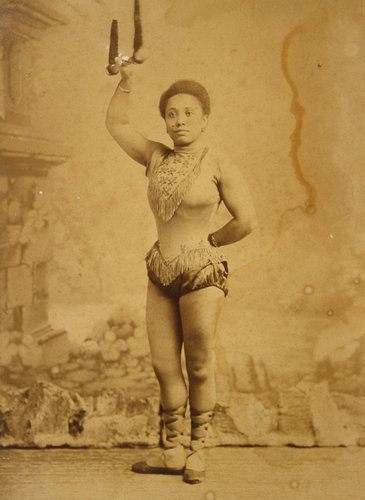

As befits a renowned performer, Miss La La went by many names in her career. “La La was billed as La Venus Noire (Black Venus) in Paris and an African Queen in London,” writes Peta Tait, professor of theater and drama at La Trobe University, Australia, in her 2005 book Circus Bodies: Cultural Identity in Aerial Performance. Her real name was Olga Brown, and she was likely born in Szczecin, Poland, in 1858. Records are sketchy about her heritage, but it is believed her father was Black and her mother white, beyond this little is known of Brown’s early days.

Brown’s introduction to the circus is thought to have occurred shortly after her ninth birthday. From then on, she literally learned the ropes, becoming adept at wire walking and the trapeze, as well as balancing acts and strong woman performances. She performed across Europe, including at the Folies Bergère in Paris, the Royal Aquarium in London, and the Gaiety Theatre in Manchester, at a time when circuses were considered, to borrow a phrase, the greatest show on earth. She was not the lone Black performer in these circuses—the circus had long been an inclusive place—but she was perhaps the best known. Among the feats she is remembered for performing: lifting a bronze cannon into the air with her teeth while hanging from a trapeze.

Brown had striking talent and undeniable stage presence, but the politics of the time—especially when it came to race—also shaped her career. Her African and European ancestry was regularly exploited to create mystique around her performance. Tait writes of a popular rumor in Victorian London that Miss La La was an African princess who lost her throne and sold into slavery when her chiefs decided to pledge their allegiance to Queen Victoria. “Admiration for La La suggests a complicated response to her identity… Perhaps La La was caught up in a European fascination of performances of an imaginary Africa,” writes Tait.

One 19th-century critic attempted to praise Brown for what she was—a woman performing extraordinary feats—but the reprehensible racial politics of the day are still very much evident in the words: “She does all that her muscular rivals have done and a great deal more. La La as we have hinted is a representative of a dark-skinned race but in the matter of strength she is prepared to assert her superiority of the boastful people who will have it that all virtues are associated with a light complexion.’”

For Marilyn R. Brown, professor of art and art history at the University of Colorado, Degas’ painting is all about race and the white male gaze. “In the representation of ‘race’ in Edgar Degas’s Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando, the precarious positioning of the acrobat’s teeth gives extraordinary embodiment to a historical moment of white masculine anxiety,” the professor writes in the essay “‘Miss La La’s’ Teeth: Reflections on Degas and ‘Race’” published in The Art Bulletin.

Politics aside, a woman cannot hang by her teeth forever. Some sources suggest she married an American contortionist and went on to have three daughters, who later formed their own circus act, the Three Keziahs. Other sources, however, lose track of her after she traveled to America. What we do know is that Olga Brown left an indelible mark on the world of performance art and in “Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando,” despite its racial undercurrents, she remains in popular consciousness 150 years later, held by iron will, still ready to dazzle.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook