On Tour With The War On Drugs: Macon, Georgia

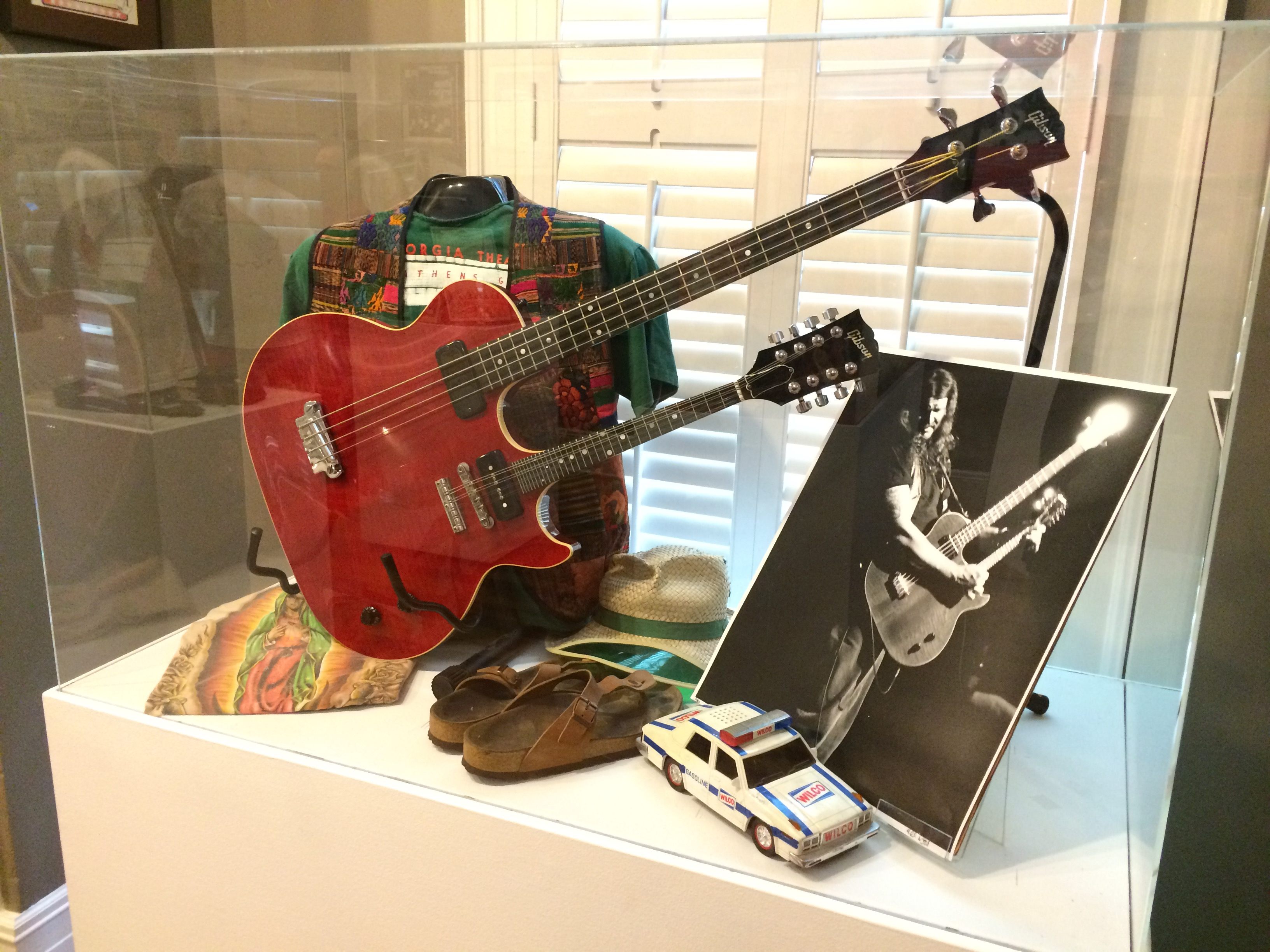

A custom bass/mandolin owned by Allen Woody. (All photos: Jon Natchez)

A custom bass/mandolin owned by Allen Woody. (All photos: Jon Natchez)

For the next few weeks, The War on Drugs’ Jon Natchez is going to be sharing his adventures on a current tour. Like any touring musician, Natchez experiences a very specific form of travel, the kind where you usually have 24 hours, tops, to explore a new city. This is the fourth installment in his Atlas Obscura tour diary; read the first one here, second here, third here.

We wake up in a hot, humid parking lot, groggy and frazzled from an exhausting day at Bonnaroo, but we’re all excited about the planned excursion for the day: a visit to the Allman Brothers Museum, aka the Big House, the one notable attraction for miles. And unlike, say, a museum full of ventriloquist dummies, this is a spot that the entire band and crew is interested in checking out.

Everyone in this group is a junkie for music history, and this kind of deep dive into a band’s past has piqued everyone’s curiosity. Our drummer Charlie, perhaps the most erudite historian in the group, had even sent everyone a little essential reading to whet our appetite for the trip. But, due to general chaos at the hotel, we don’t get settled and checked in until 3pm. Because of the lateness and general annoyance, there’s a communication breakdown, and some folks—most notably Adam, the band’s singer and lead guitarist, who had been hugely excited for the trip—have been told an erroneous lobby-call time and they miss the outing. It’s an all-too-familiar tour experience: tour managers always talk about how organizing a band is like trying to keep puppies in a basket, and sometimes, in all the chaos, a puppy or two (or five) get left behind in a crappy hotel.

I normally have a rule against taking photos from stage, but I had to document this moment from the Bonnaroo Superjam the previous night, when I got to fulfill some massive childhood fantasies and play some music with, among other awesome folks, D.M.C. Also serendipitously pictured: longtime Allman Brothers bassist Oteil Burbridge.

But those of us who make the journey get treated to a really fun afternoon. Our bus driver Bob—whose nickname (self-given! proudly!) is “George Costanza”—is on his way into town for food, so even though he’s off the clock, he gives us a ride over to the museum. We’re welcomed by Rob, the museum’s director and enthusiastic evangelist, who hands us off to Richard, the museum’s “Director of Collections and Merchandise”, who guides us through the building. Another potential title for Richard: “Man Who Knows More About The Allman Brothers Than Anyone Else Ever”. Close your eyes, and picture an Allman Brothers expert. That’s Richard: a big. barrel-chested man with a scraggly, bushy dark beard and a syrupy, slow Georgia drawl.

He takes us around the museum, and he has the complete history of the group at his fingertips. He can tell a long, detailed story about every item there, and the museum is crammed full of band-related memorabilia, everything from the epic—Duane Allman’s legendary 1957 goldtop Les Paul (and normally I hyperlink to external websites but it’s just awesome that www.duaneallmansgoldtop.com exists), the instrument featured on one of the most famous guitar moments in music history.—to the ephemeral—displays full of hotel room keys, parking slips, and shoes.

Outside the Big House.

Granted, there is something perverse about this whole exercise—namely, that we’re a bunch of musicians taking a break from tour by looking at mementos of another band’s touring. There’s even a little replica of a guitar tech station, with a guitar, guitar rest, and tuner.Dominic, our guitar tech, runs over and excitedly starts fiddling with it. Even on a day off, it’s immensely satisfying to enter another band’s world. All people, I think, feel a comfort and ease when surrounded by members of our own cultural tribes, but that sense of community is heightened when your shared experiences are, like touring is, both more intense and more unusual than the average workaday experience. I’m not trying to say that touring is some exalted existence that common peons could never understand; in many ways, the reality of earning a living as musician is more similar to other trades than most people imagine. Still, touring musicians generally love getting together, hanging out and swapping stories, just because it’s so nice and comfortable to be around people who share this unusual peripatetic existence and the strange compulsion to get up on stage and play music.

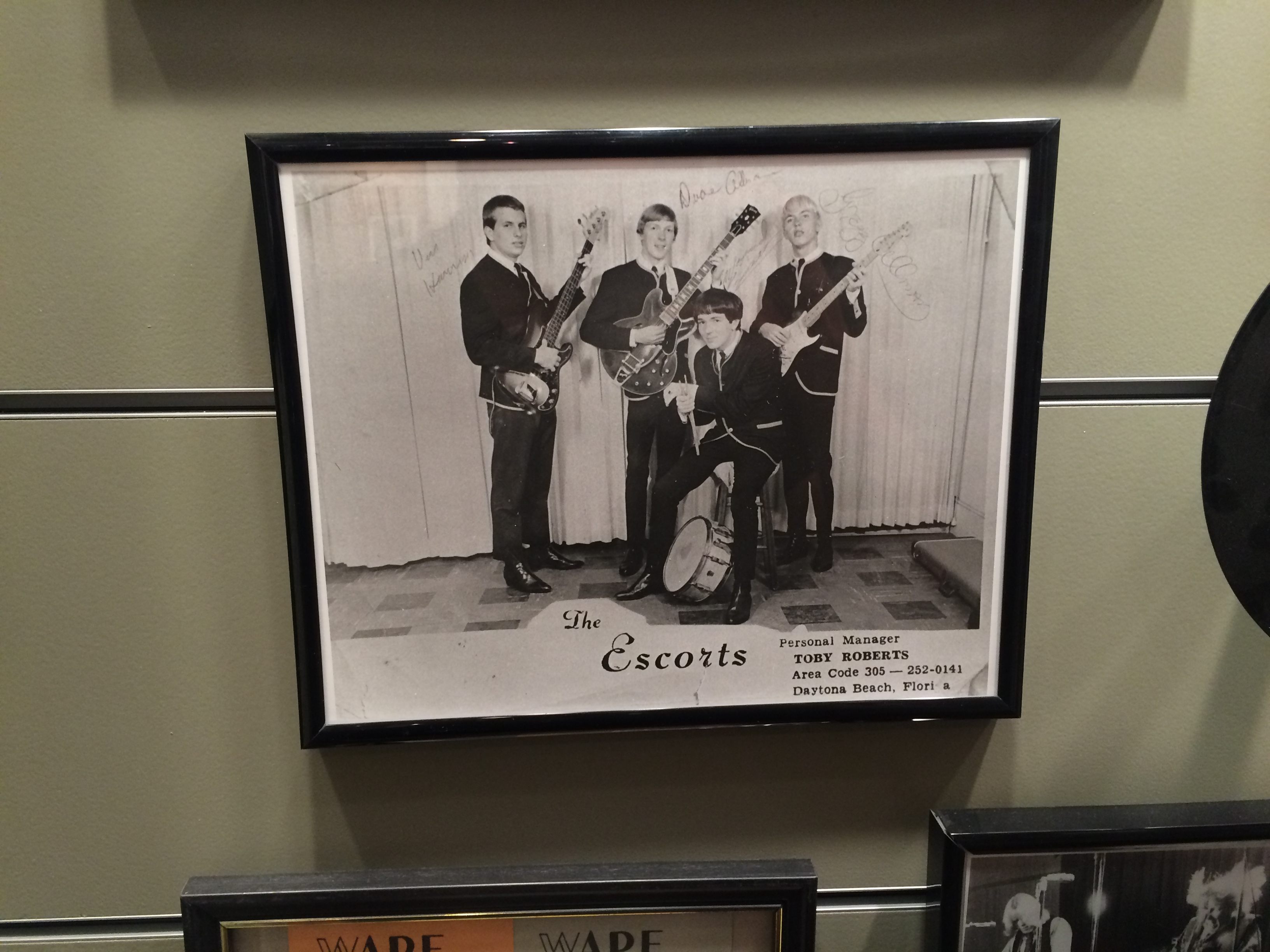

A promo photo of one of Duane (second from left) and Gregg (far right) Allman’s early bands. They later (true story) changed their name to The Allman Joys.

A promo photo of one of Duane (second from left) and Gregg (far right) Allman’s early bands. They later (true story) changed their name to The Allman Joys.

The Allmans and this house in particular exemplify the way a band can feel like a family. The band had moved from Jacksonville, Florida to Macon to record for Macon-based Capricorn Records (our tour manager, Craig McQuiston aka Q, used to be in another Capricorn band, The Glands). Berry Oakley, Duane Allman, their families, and Gregg Allman all moved into this big ramshackle house right on Highway 41. It became the hub of band activity, where they’d all hang, jam, write, and party. The family circle also encompassed the band’s long-serving crew, which you’d expect given the band’s legendarily prodigious touring. (On the jacket design for their famous record At Fillmore East, the band is on the jacket cover and the crew is on the back).

A belt we wished we could steal for our keyboard player Robbie.

We take our time going through the place, which is basically just full of fun stuff. There’s a lot of darkness and death in the Allman Brothers story, but the museum focuses on the more blithe side of the band’s legacy. There are great photos of early, pre-Allman Brothers musical projects, colorful 60s and 70s concert- and casualwear, lots of gorgeous vintage show posters. As devoted gear nerds, we have a blast looking at Allen Woody’s crazy bass creations, Jaimoe’s preposterously thick drumsticks, and various amps and other pieces of musical miscellanea. But the undoubted highlight of the day occurs as we’re winding down the tour, wandering through the upstairs bedrooms. Richard, who had quietly drifted away from the group, suddenly appears holding Duane’s ’57 goldtop, and asks us if we want to take it for a spin.

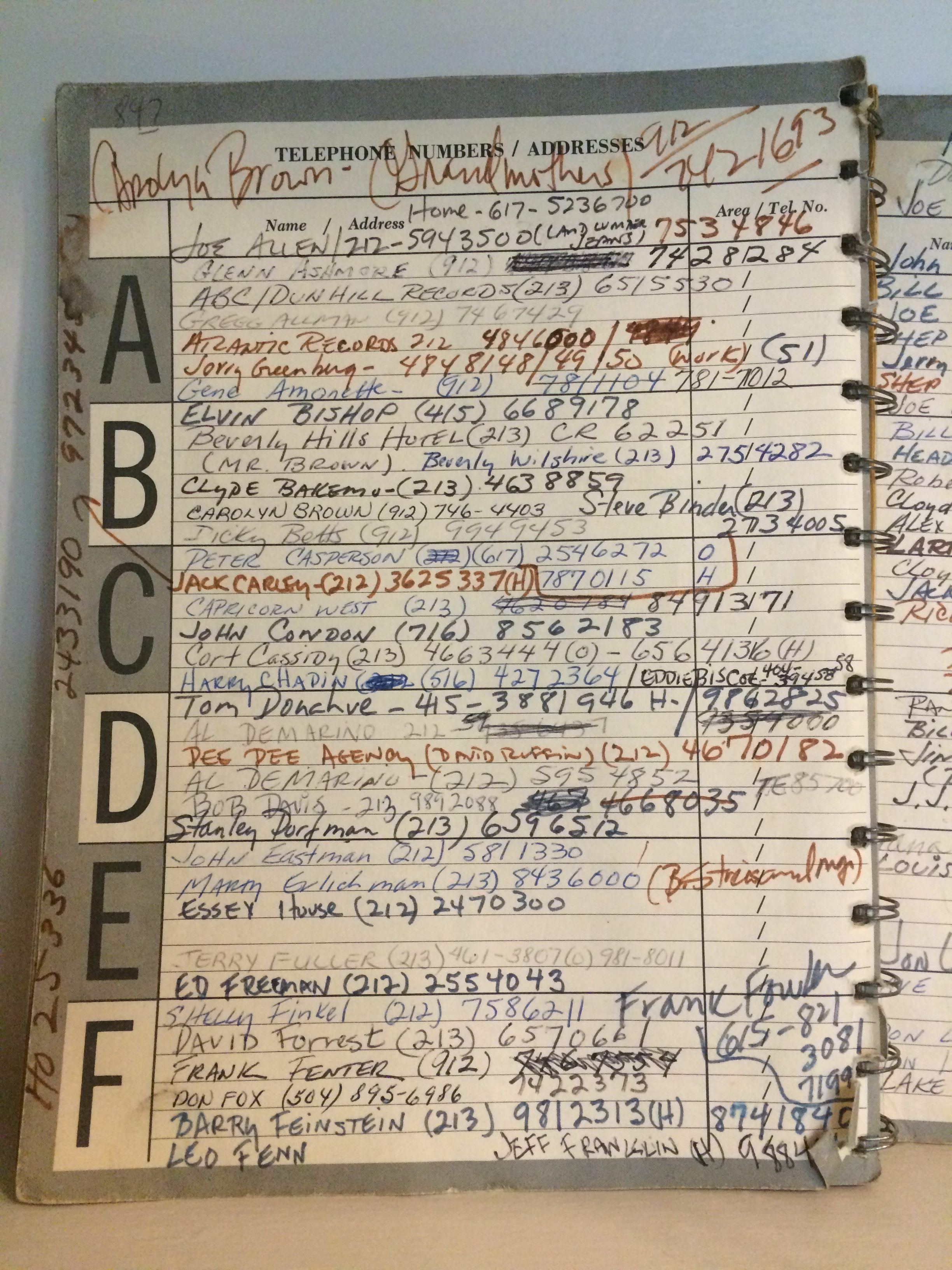

A page from the Allmans’ tour manager’s phone book. Lots of these names are industry icons of the 1970s, like Atlantic exec Frank Fenter, Top of the Pops director Stanley Dorfman, guitarist Elvin Bishop, plus, of course, the numbers of Gregg Allman and Almann Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts.

A Gibson Custom Shop copy of one of Duane’s guitar, presented as a gift to his daughter, featuring his name spelled out in frets.

Dominic and Q ponder some amps.

Dominic and Q ponder some amps.

It’s important that you understand how insane and unexpected an opportunity this is. Imagine going to Cooperstown and the curator suddenly asking if you’d like to play catch with Willie Mays’s glove. We are speechless. But we each, in turn, sit down on a couch, plug the guitar into an amp and play a little. It is thrilling and beyond terrifying. I’m far from a great guitar player to begin with, and when my turn comes, my fingers and arms are tight with stress and fear. It’s not so much that I’m imagining dropping this priceless guitar—although that’s part of it—as much as I’m feeling completely unworthy to be piddling about in my amateur way on this instrument that has produced such iconic music. I mash through some chords and lines, grateful that I’ve done it, but quickly pass the guitar back to Richard.

Q prepares to rock the Layla Guitar.

Q prepares to rock the Layla Guitar.

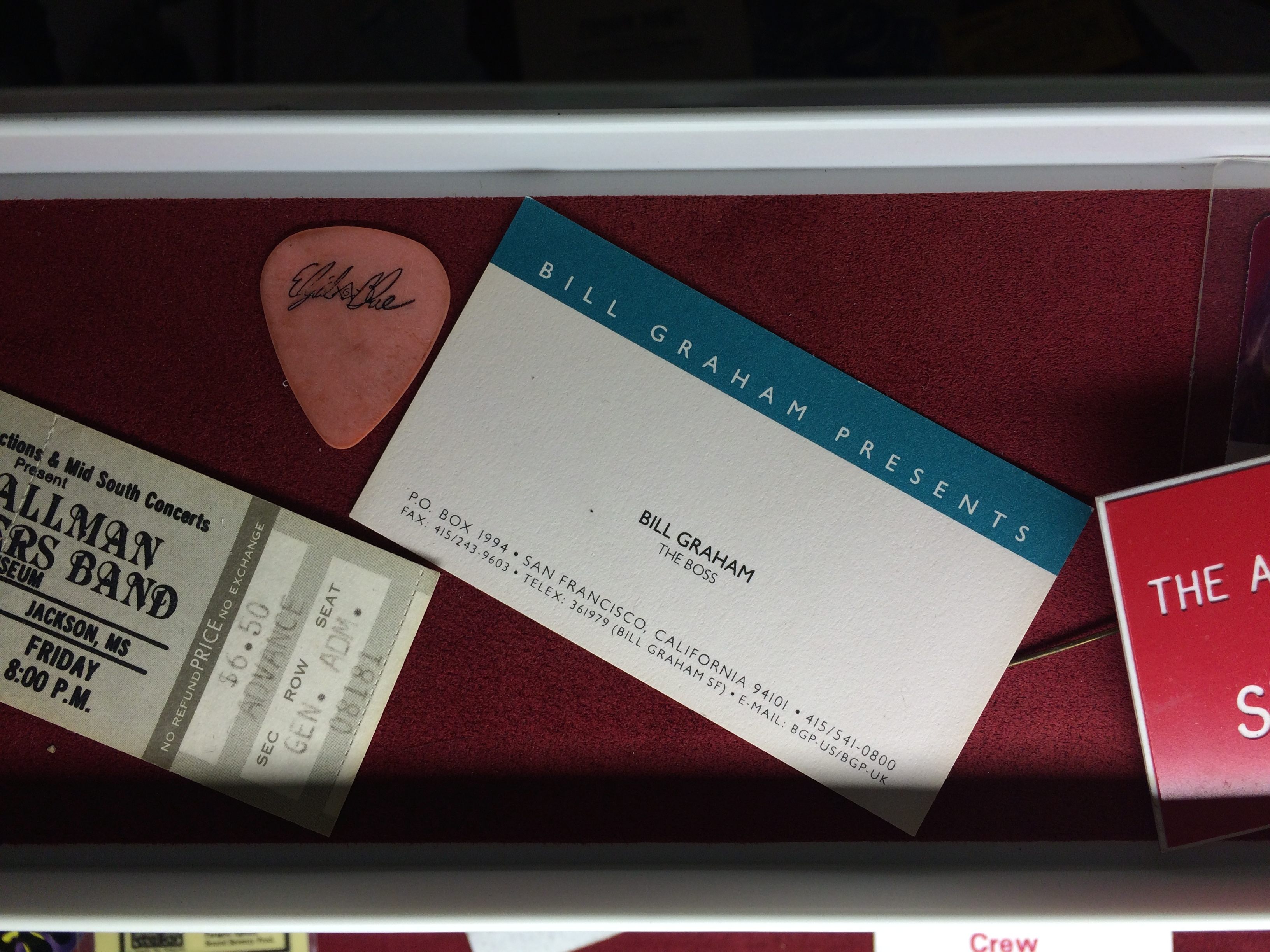

Remember when everyone had to have a business card? I was especially excited to see that Bill Graham’s card says “The Boss”

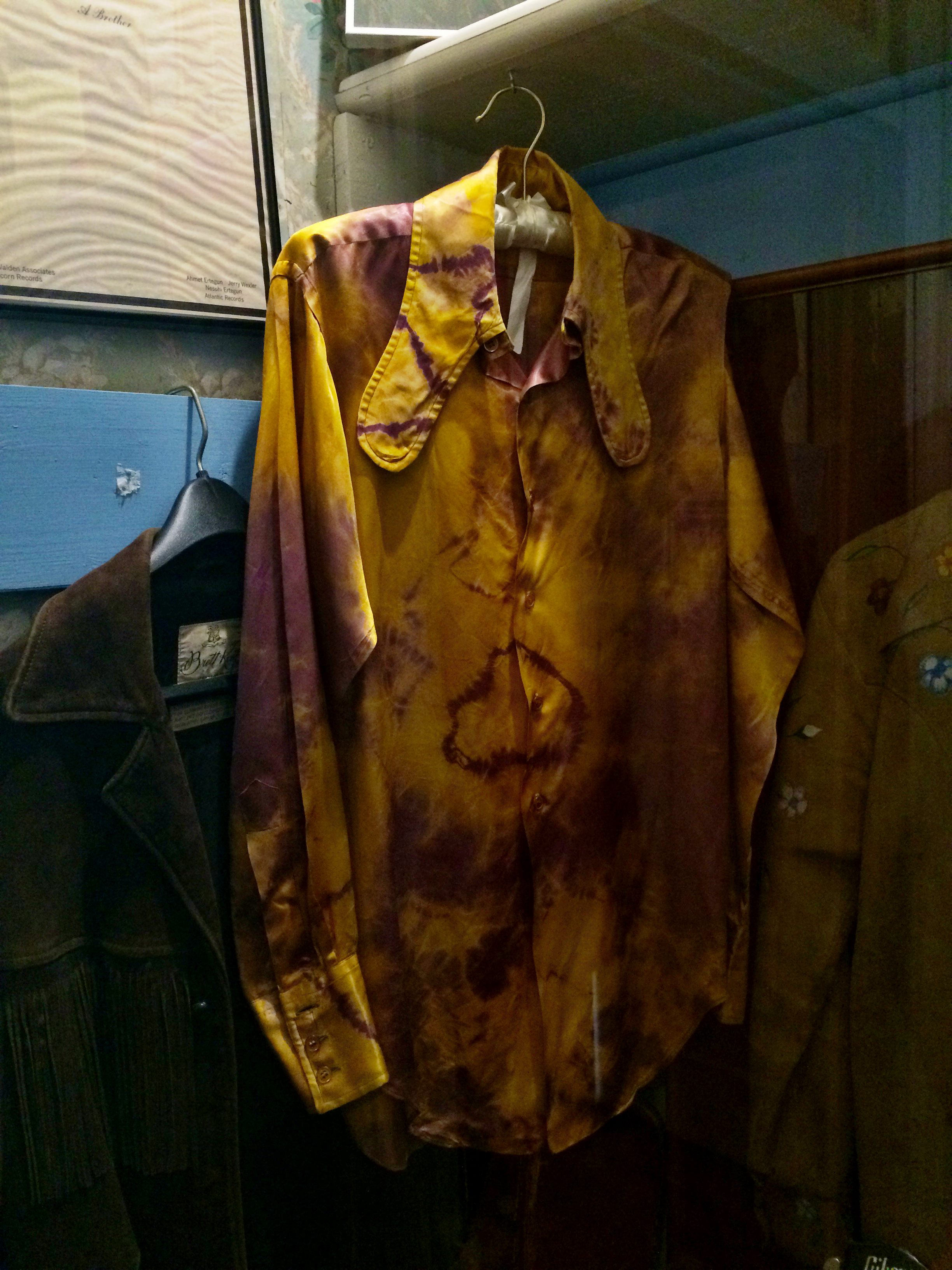

Shirt that Eric Clapton gifted to Duane Allman. The late 60s/early 70s were an interesting time for collar technology.

Shirt that Eric Clapton gifted to Duane Allman. The late 60s/early 70s were an interesting time for collar technology.

One more thing to do: go out behind the museum, where they’ve recreated the At Fillmore East backdrop, and take some photos. Extremely touristy, yes, but too good to pass up. That accomplished, we’re about to call a couple cabs to go downtown to grab some food; Rob insists, however, that we let him drive us to his favorite place to eat in town, so we pile into his van and he joins us for a ridiculously delicious and filling meal at a place called the Rookery, though none of us is bold enough to order the “Jimmy Carter” burger featuring peanut butter and bacon.

Band- and crewmembers posing together for our Fillmore East shot. We don’t draw the same distinctions that the Allmans did. From L-R: Front—Craig “Q” McQuiston, tour manager; Robbie Bennett, keyboards; Dominic East, guitar and stage tech; Back—me; Charlie Hall, drums; Anthony LaMarca, guitar and keyboards; Dave Hartley, bass.

Over dinner, Rob tells us how he got involved in the Big House: a longtime fan of the band and former New Yorker, he used to run a transportation business specializing in musician and performer transportation. He drove for the Grateful Dead and other groups, but always had a special place in his heart for the Allmans. Through his connections, he started working for them manning a door when they would do their legendary Beacon Theatre runs. He got more and more integrated into the band’s extended family, and when the opportunity came to run the museum, he pounced, moving his family from New York down to Macon. He does seem like a man completely excited about the work he gets to do, living in this cordoned-off world he first idolized from afar. It’s a feeling everyone in our band—anyone in any band—can relate to.

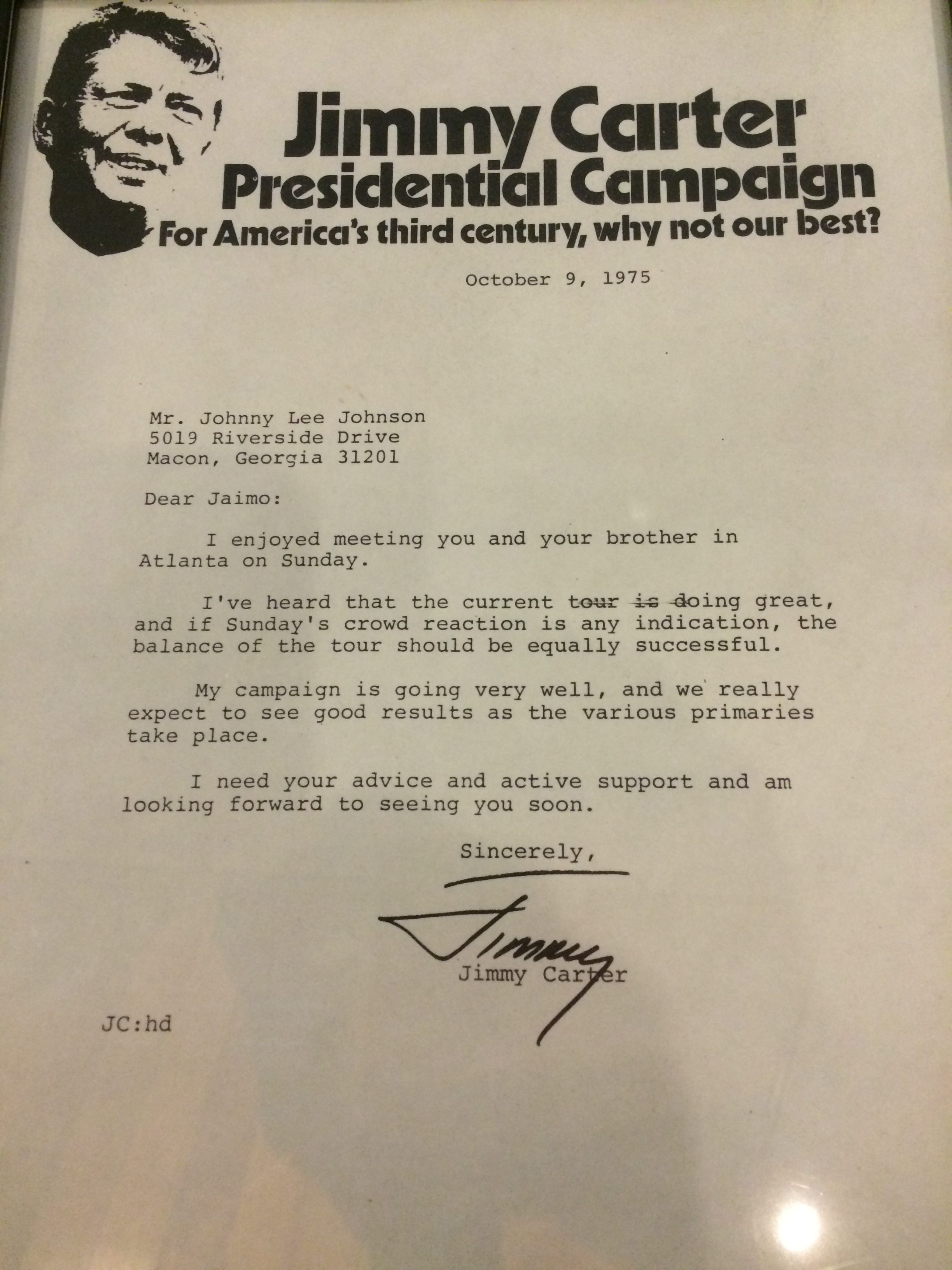

A memento from another of Georgia’s favorite sons: Jimmy Carter’s letter to Jaimoe (note: Jaimoe misspelled, as is his full name, which is John Johan Johanson or Jai Johanny Johanson).

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook