Oxyrhynchus, Ancient Egypt’s Most Literate Trash Heap

An ancient Egyptian landfill of plays, gospels, and mash notes gives new meaning to trashy writing.

Bernard Grenfell (left) and Arthur Hunt (right) outside their tent in the Delta. (Photo: © The Egypt Exploration Society)

Although Pompeii and King Tut get the biggest headlines, the most informative archaeological site ever discovered isn’t a town, temple, or tomb: it’s a massive garbage heap near (and partly underneath) El-Bahnasa, Egypt—a place called Oxyrhynchus.

If you don’t produce garbage, to a large extent you don’t exist to historians. Trash heaps—or “middens,” in archaeological parlance—are records of everyday life, the stuff so obvious (or embarrassing) you’d never bother to write it down. The same problems that bedevil landfills today, like the anaerobic environments that stop compressed trash from breaking down, are exactly what preserved the archaeological record of Britain’s transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age (East Chisenbury), Japan’s Jomon-era development of trade and rice farming (sites throughout the Japanese archipelago), South African settlements during the Pleistocene (Elands Bay Cave), and more. And since trash piles up in strata as it’s created, it forms its own easy-to-read timeline.

Even among the MVPs of well-preserved trash, Oxyrhynchus is something special. It’s in a desert where it never rains, and it’s well outside any river’s flood plain. It was a multi-cultural crossroads which was alternately part of the Nubian, Persian, Greek, Ptolemaic, Roman, Byzantine, and Fatimid empires. It held some of the earliest Christian monasteries and one of the oldest Egyptian mosques. Most importantly, it was a dumping ground for hundreds of thousands of pieces of papyrus—a wide-ranging library of classical texts, official records, personal correspondence, and grocery lists.

It’s basically the closest thing we have to discovering the Library of Alexandria in a landfill. Academics familiar with it throw around terms like “unparalleled importance” and “holy grail” and aren’t trying to be hyperbolic. It contained a lot of other ancient literature that would otherwise be totally lost–most famously a Sophocles comedy and the poetry of Sappho–not to mention extensive details about everyday life in Egypt, Greece, and Rome. It also held the biggest cache of early Christian manuscripts ever discovered.

The location of Oxyrhynchus, Egypt. (Photo: Yomangani/Public Domain)

Papyrus is much more durable than the wood-pulp paper we use today—durable enough to survive for 2,000 years. That alone wouldn’t matter if it weren’t for papyrus’s other advantage: unlike vellum or parchment, it was cheap. As a result, although literacy in Ancient Egypt wasn’t widespread by modern standards, the people who were able to write were able to write a lot, to such an extent that bureaucratic note-taking became its own cultural imperative—and that writing stuck around, at least partly because it wasn’t expensive enough to be worth stealing or repurposing. (It did sometimes make good packing material, notably to wrap mummies.)

When the Greeks moved in around 300 B.C., in numbers large enough to swell Oxyrhynchus until it was Egypt’s second or third largest city, they assimilated to the existing Egyptian scribal culture. For the next 900 years, Oxyrhynchians wrote jokey notes to each other, and threw them away. They made copies of popular plays, and threw them away. They kept records of the transition to Roman rule, the formation of a large Coptic Christian community, and the annoyances of running a host of businesses.

Their trash includes otherwise unknown Sappho poems, previously lost biblical texts like the Gospel of Thomas, snippets of sheet music. It’s an overwhelming and still mostly-untranslated tapestry of documents that gives us our clearest picture of everyday life in a transformative historical period. Critically, they wrote a lot of it in Greek. And then off to the landfill it went.

So life might have continued indefinitely, were it not for the Arab conquest of Egypt in 640 A.D. The new government was unwilling or unable to maintain the canal system that made the desert settlement livable. Oxyrhynchus and its welcoming trash heap was abandoned; its scribes, monks, and ordinary residents relocated to towns and cities with functional water sources.

With the exception of a brief attempt at reoccupation by the Fatimid Caliphate from around 950 to 1171, Oxyrhynchus spent the next few centuries sinking into disrepair. The town moved from the bustling metropolis of times past to a small religious center for the study of Shia Islam. By 1400, it was a ghost town, a sand-filled ruin doomed to fade from memory.

Then, in 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt and started to loot it. He knew nothing about art, so he brought along someone who did: Jean-Dominique Vivant Denon, imperial Minister of Arts and the man who would essentially create the Louvre museum. Denon was a rare noble-blooded survivor of the French revolution; before going to work for Napoleon, he’d been a diplomat and art procurer for Louis XVI.

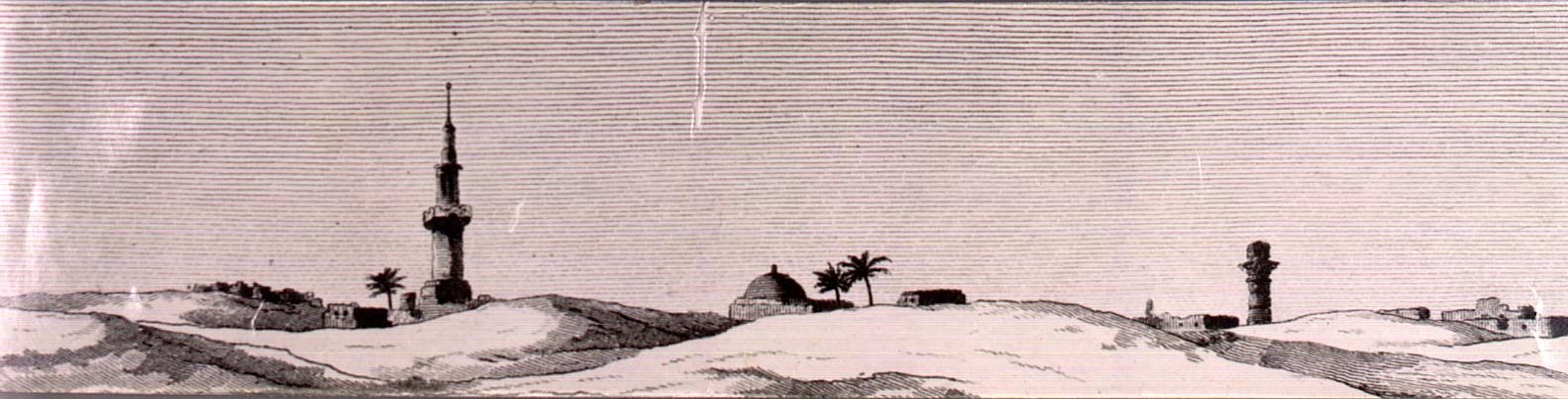

While Denon was in Egypt, he didn’t simply offer advice on what might make good plunder; he focused on using his formidable artistic skill to produce detailed drawings of any temples and ruins the army passed by—including the few towers of Oxyrhynchus which remained above the sand, in an image which coincidentally includes the buried (and certainly unrecognized) trash mounds as a landscape element.

A drawing of Oxyrhynchus made by Baron Vivant Denon in 1798. (Photo: Courtesy Imaging Papyri Project, Oxford/All rights reserved)

When Denon released his Egyptian sketches as a folio, along with an account of his voyage, it kicked the Egyptian Revival into high gear in both France and in England. Egyptian patterns were everywhere, sometimes copied directly from Denon’s drawings: in furniture, in architecture, and on clothes. Egyptian artifacts were displayed at the Louvre and the British Museum. Obelisks went up as public monuments in Paris, London, and Washington, D.C. Spiritualists held Egyptian-themed seances. Decorating a room in the “Egyptian” style, or traveling to Egypt itself, no longer seemed eccentric: what had been a niche aesthetic interest was now pop culture. By 1882, a group of wealthy Egypt-obsessed Victorians had banded together to form the (ongoing) Egypt Exploration Society, with a stated goal of properly excavating neglected ancient sites.

It is at this point we meet the protagonists of the modern Oxyrhynchus story, our papyrus excavators, the academics Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt. They were nowhere near as glamorous as the ex-Baron Denon, whose drawings had mapped the site of their eventual archaeological dig. They were nerdy friends who liked to hang out and translate classical texts together. They weren’t even Egyptologists, let alone fieldwork guys. They liked Classical Greece and Rome. But they soon realized that nobody was looking at Greek papyrus, and that there was potential grant funding available.

Grenfell started making short trips to Egypt. When the Egypt Exploration Society agreed to broaden their interest to include Greek and Roman ruins in Egypt, Hunt and Grenfell were already on the ground, and they had a likely site: they’d heard locals were pulling scraps of Greek writing out of the sand near El-Bahnasa. Grenfell had a hunch it might be the motherlode. Was it ever. Between 1897 and 1907, they unearthed more than 500,000 papyrus fragments, more than they could possibly translate in their lifetimes.

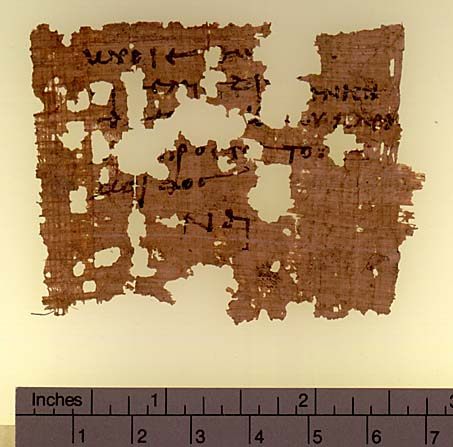

Manuscripts that were excavated from the site were shipped directly back to Oxford University. (Photo: © The Egypt Exploration Society)

They quickly realized that once the protective seal of hardened dirt atop a mound was breached, any papyrus left behind would be exposed to the elements (chiefly water, sun, and sand) and would rapidly dissolve or bleach away. Studying tray-by-tray in situ, today’s gold standard, would be impossible; they needed to get all the paper out of the ground as quickly as possible, without even stopping to translate a word or two. As Grenfell describes the dig:

“The workmen are divided into groups of 4 or 6, half men, half boys, and in the beginning are arranged in a line along the bottom of one side of a mound, each group having a space two meters broad and about three metres long assigned to it. At Oxyrhynchus the level at which damp has destroyed all papyrus is in the flat ground within a few inches of the surface, and in a mound this damp level tends to rise somewhat, though of course not nearly as quickly as the mound rises itself. When one trench has been dug down to the damp level, one proceeds to excavate another immediately above it, and throw the earth into the trench which has been finished, and so on right through the mound until one reaches the crest, when one begins again from the other side.”

They shipped cases full of manuscripts back to Oxford College, preserved in whatever tins were available; they recovered so much papyrus they had to improvise, in one instance using a cookie box. Indiana Jones derring-do, it was not. But it worked, as did bonus payments to disincentivize workers from running off with what they found.

Excavating the site. (Photo: © The Egypt Exploration Society)

After more than a hundred years of steady effort by hundreds of scholars, we are still nowhere near transcribing everything that came out of the ground in that single decade. Nor the additional papyrus found by Italian digs in the 1920s and 1930s. Nor the further recovery by a Kuwaiti team in the 1980s. The current dig, ongoing since 1992, is more focused on the city’s buildings, and is the work of a joint Egyptian/Catalan team led by Josep Padró. They made international news in 2014 when they discovered what may be one of the earliest known paintings of Jesus Christ in the tunnel of a temple to Osiris.

In theory, you could visit the site yourself; with all the archaeological comings and goings, a populated town of about 20,000 residents surrounds it again. Then again, as Peter Parsons wrote in City of the Sharp-Nosed Fish, maybe the Oxyrhynchus most worth touring is “a waste-paper city, a virtual landscape which we can repopulate with living and speaking people.” Most of the papyrus sent to England by Grenfell and Hunt remains, in a sense, undiscovered. Despite a hundred years of steady work and at least 77 published volumes of papyrus, with 40 more planned, as of 2011 it was estimated only 2 percent of the Oxyrhynchus papyri have been translated.

The Oxford Archives have invited anyone with an internet connection to join the deciphering team. You don’t even have to be able to read Greek (or Pahlavi, or Coptic, or Arabic, or Persian). All you have to do is visit the Ancient Lives site, look at scans, and press the letter buttons that resemble the shapes you see.

Or maybe you could take the trash out to the curb, and congratulate yourself on building one small piece of a future Oxyrhynchus.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook