How Rebuilding New Jersey’s Palace of Depression Became a Family Legacy

Built from recycled materials by an eccentric con artist in the 1930s, the curious creation was demolished—and then reborn.

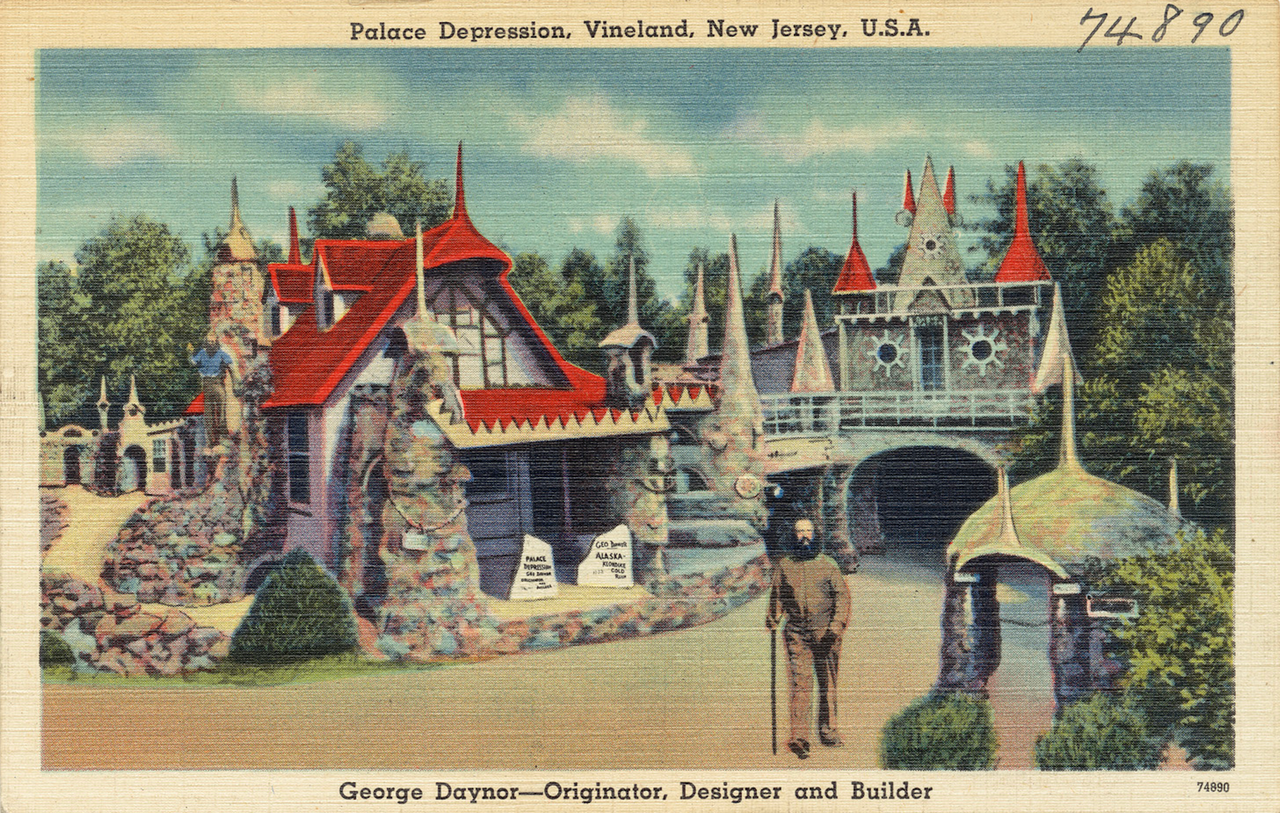

Nearly a century ago, a stranger arrived in Vineland. With flowing hair and a wild beard, he stood out in this quiet southern New Jersey town. He called himself George Daynor, and said he’d lost most of his fortune in the stock market crash of 1929. He used what little money he had left to buy four swampy acres near a stream. It was there that he constructed what would become known as the Palace of Depression. Using mud, concrete, and whatever junk he could find—auto parts, bottles, bed frames—Daynor built a house with towering spires. Daynor also built something else: a web of mistruths and lies, one of which eventually landed him in prison. He passed away in 1964 and his hand-built palace fell into disrepair. It was razed by the city of Vineland in 1969.

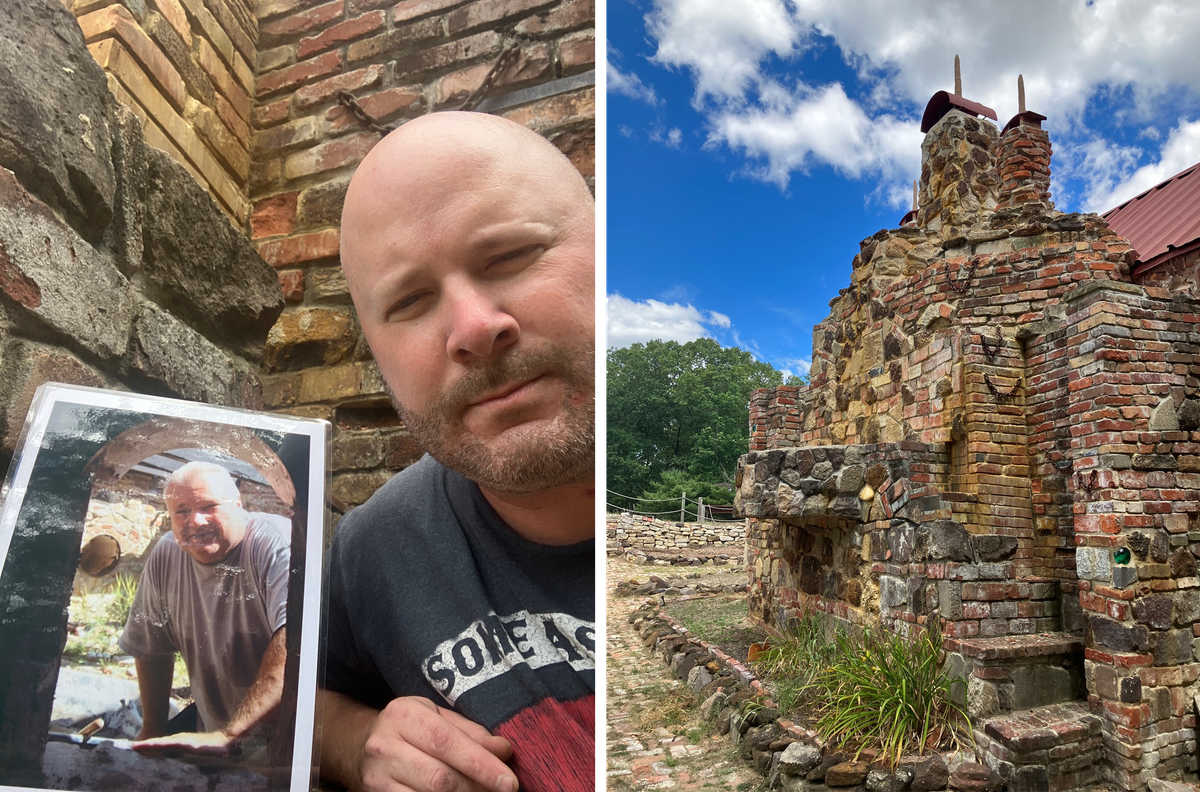

Almost 30 years later, the city decided to sell the site to developers. When those plans landed on the desk of Kevin Kirchner, Vineland’s director of license and inspection, they jogged childhood memories of visiting the place. He came up with a plan of his own: He would rebuild the Palace. Other locals quickly embraced the cause. Using recycled materials and relying on donations, over the years a small group of volunteers reconstructed Daynor’s junk house on the same spot as the original. In December 2021, the Palace still unfinished, Kirchner passed away from Covid-19 complications. His son Kristian Kirchner has vowed to complete his father’s work, and hopes to one day open the Palace for tours.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Kirchner about what sparked his father’s original idea and his own resolve to see it through, as well as who George Daynor really was—spoiler alert, that wasn’t even his real name.

What connection did your father have with the original Palace of Depression?

In the 1950s, his father would take him to visit it. After so many visits, my father was borderline fascinated with it, borderline scared to death of it. He compared Daynor to the wolf man from the old Frankenstein movie [Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man] because he had a big, flowing beard. And the place kind of stuck with him his whole life.

How did he start the rebuilding project?

According to my father, in 1998, when the city planned to sell it, there was still a “structure” on the property, the ticket booth. The licensed construction official (my father at the time) had to sign off that the structure was suitable for demo so that the lot could be sold and developed. Instead he got on the phone with some contractors and within an hour or two he had about 400 to 500 people who were committed to helping him. From there he officially presented the idea to the city and got approved for a rebuild of the palace.

What did you discover about George Daynor?

I knew at some point he became involved in a kidnapping case—in 1956 or 1957, I think it was. A baby had been kidnapped in New York. Daynor heard about it through the news media and sent a telegram to Walter Winchell, a radio host, saying that the kidnappers had come to the Palace and wanted to exchange the baby for ransom. Turns out, it was all a publicity stunt. The FBI charged him with fraud. So I did a Freedom of Information Act request and got his whole file. I also went to Atlantic County Court, which is where he was sentenced, and got his whole sentencing file. And in reviewing them, it proved that everything Daynor said was pretty much a fairy tale. It was just simply to draw attention to the Palace to make it famous. His actual name was Charles Diener. He was a builder from Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. I have no idea why he changed his name, or what he was running from. That was one thing that the records did not make clear.

How is the new Palace different from its predecessor?

We couldn’t do it exactly as Daynor did it, obviously, because of modern construction codes and safety reasons, but there are parts of the building that are exactly like Daynor had them. All we had to go by were pictures, we didn’t have any blueprints that Daynor left behind. And everything here is a hundred percent volunteer. We’ve raised all the funding ourselves and operate entirely off donations.

Why take up your father’s lifework?

Every part of this building, every part of this museum had his heart and soul all over it. For what he started and the amount of work he put into it, I think it’s important that we keep it going and finish it. My father got to the point where he just wanted to bulldoze the whole project a couple of times, but he was determined to show people what you can do. I simply want to show people what can be done in the face of adversity with sometimes only sheer willpower alone.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook