Pig Remains Show How Far Prehistoric People Traveled to Visit Stonehenge

Epic Neolithic feasts drew crowds from opposite ends of Britain.

It turns out that Stonehenge has been drawing visitors from all over for thousands of years. A gathering place for ceremonial Neolithic feasts, the iconic, enigmatic structure down in southern England may have been welcoming pilgrims from as far away as Scotland, according to new research published today in the journal Science Advances.

Analyzing isotopes from the bones of 131 pigs, which are known to have served as these feasts’ featured entrées, the researchers were able to trace the animals’ origins to a wide range of locations around the modern-day United Kingdom, including contemporary northeastern England and western Wales. In a press release, the lead author Richard Madgwick of Cardiff University said that these findings shed new light on the “scale of movement and level of social complexity” inherent in these prehistoric gatherings.

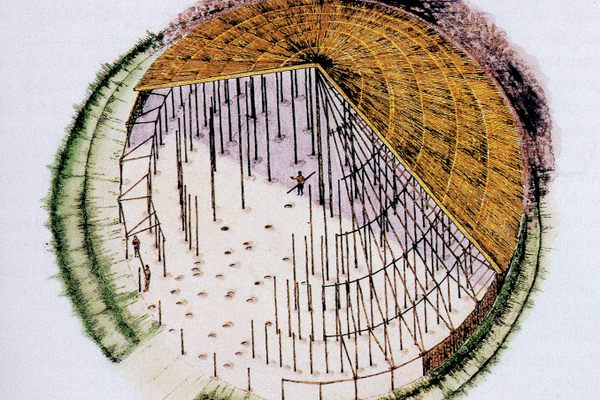

The researchers studied pig bones from four different sites—Durrington Walls, Marden, Mount Pleasant, and the West Kennet Palisade Enclosures—with close proximity to either Stonehenge or Avebury, an analogous Neolithic site of arranged stones. The prehistoric peoples who built Stonehenge or Avebury might have lived at these other sites, and then gathered at the monuments for ceremonies marking, perhaps, the midwinter sunset. (English Heritage points out that Stonehenge was “built to align with the movements of the midwinter and midsummer sun,” and that many of the pig remains indicate that the animals—likely born in springtime—were slaughtered at nine months old, during winter.)

During their analysis, the researchers looked at strontium to assess the animals’ native geologies, oxygen for their climates, and sulfur for their distances from the coast. They found isotope values covering “all the biospheres of Britain” and even some coastal influences, despite the henge sites’ locations more than 30 miles inland. The remains’ geographic diversity, said Madgwick, indicates that these feasts “could be seen as the first united cultural events of our island,” events that may have enforced some rather strict ceremonial codes. Pigs are more difficult than cattle to transport over long distances, meaning that there was likely a kind of symbolic significance attached specifically to eating pigs in order to justify that labor. Moreover, feast attendees apparently felt an obligation to supply the south with their own local fare, highlighting the lengths people had gone to in order to converge. The remains suggest the existence of a transregional cultural identity among prehistoric Britons, at a time when such contact required treacherous levels of effort and care.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook