Before Plymouth Colony and the Pilgrims, There Was Patuxet

Slavery, plague, and territorial conflict likely made the Europeans’ arrival on Wampanoag land possible.

More than 400 years ago, the coastal community of Patuxet was one of dozens belonging to the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, spread across much of what’s now New England.

The Wampanoag called the region home for more than 12,000 years, but most history books have reduced them to a footnote. Today, schoolchildren typically learn only that the tribe helped the Pilgrims survive their first year at Plymouth, established where Patuxet once stood. To show their gratitude, the European arrivals invited the Native Americans to a meal, with Patuxet-born Wampanoag Tisquantum (Squanto), who happened to speak English, serving as translator. Missing entirely from the familiar history, however, are critical details, such as how Tisquantum learned English, and why Patuxet was abandoned before the Pilgrims arrived.

Steven Peters, a Mashpee Wampanoag, has developed content about his ancestors’ story for exhibits and cultural programs, most recently Plymouth 400, a multinational collaboration examining the Pilgrims’ landing in 1620. Atlas Obscura spoke with Peters about the place his ancestors called home, and how he is helping to bring its story to a wider audience.

What was Patuxet like before contact with Europeans?

There were some 69 villages throughout the New England region that were part of the Wampanoag nation. It’s estimated that there were upwards of a few thousand Natives per village. In the summer months, we lived closer to the water where food was more abundant, and then as the weather got colder, we moved inland. Beyond that, we know there was a government structure, with delegates from each village who would meet with each other, discussing issues and collectively making policies and rules that would be in the best interest of everyone. The villages were pretty much in constant communication with each other. I have to think that it was really an idyllic setting where you lived off the land. There seemed to be an abundance of food for everyone.

The Wampanoag had contact with English traders and explorers before the Pilgrims’ arrival in 1620. What stands out to you about those earlier interactions?

Around 1614, we really start to see a rapid shift—the tipping point—in the impact that the Europeans are having on the Wampanoag nation, in part because of slavery, but also because of disease and sickness that was brought with them as well.

In 1614, some traders came into the region. One of them was Thomas Hunt, who docked off of the village of Patuxet. For one reason or another he decided to take some of the young men as slaves. One of them was Tisquantum, who they take back and sell (in Europe*). It’s important to understand that’s how Tisquantum learns English (before being able to return to Patuxet around 1619).

The Europeans also desecrated Native graves. They referred to the Natives as savages for a reason: it allows you to dehumanize. It allowed them to not treat us with the same rules they would a European. Desecrating graves would not have been against their moral code, because (to them) we were not human.

You mention the Europeans brought disease with them as well. How was Patuxet affected?

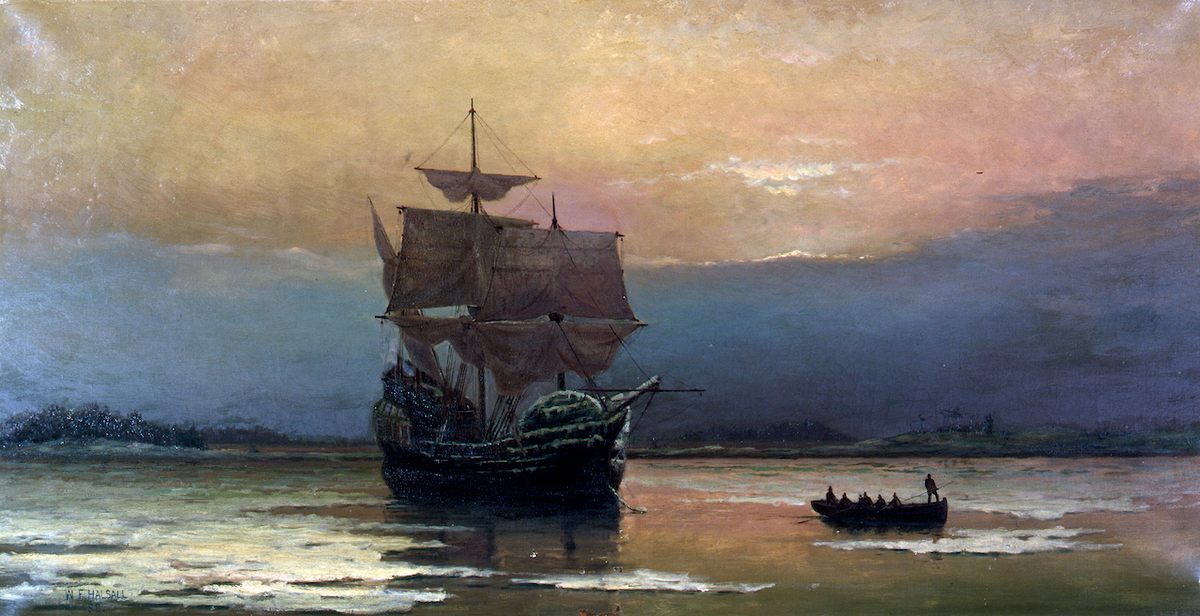

In 1616, we think the village of Patuxet becomes ground zero for what became the Great Dying. There was a plague that ripped through the Wampanoag nation where there are estimates of over 100,000 Wampanoag dying in just three short years. There were accounts of a French fishing ship that had wrecked off the coast of Patuxet, and of some of the fishermen coming into the village exhibiting signs of sickness, with yellowing of the skin and fever, and dying. Shortly after that, the plague just starts to rip right through the Wampanoag nation. Everyone in Patuxet either dies or fled the village, and they never returned. And that’s how the village of Patuxet ends up vacant in 1620 when the Pilgrims arrived. We know that the Pilgrims knew about the Great Dying, and they also must have known that that village of Patuxet was empty when deciding to make that Plymouth Colony.

In 1620, when the Pilgrims arrived, why do you think the Wampanoag allowed them to stay?

There’s so much going on between 1619 and 1620, (including) a feud going on with another tribe on our border in Rhode Island, the Narragansett, who were encroaching on our territory. The Wampanoag are in desperate need of an ally. That creates this awkward place where the Pilgrims come in, it’s a harsh winter, the Pilgrims need help, the Wampanoag need help. Had the Pilgrims landed at any other point, I don’t think they would have been welcome.

Most of what’s traditionally taught about the first Thanksgiving comes from Mourt’s Relation: A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, written around 1621. But what really happened?

I think there’s one tiny passage in (Mourt’s Relation) that says 90 warriors arrived, they stayed for three days, they ate, they played games and they left. Those 90 warriors would have vastly outnumbered the Pilgrims. Typically, when you look at an image of that quintessential Thanksgiving holiday feast, there’s more Pilgrims than Natives, there are men and women Natives, and the Pilgrims are feeding the Natives and hosting them… I don’t think the Pilgrims would have sent out an invitation (for) 90 men—it would have been extremely uncomfortable! You would have immediately been aware of just how precarious your position was, and that at any moment you could be wiped out. I think as far as my ancestors go, Ousamequin (the Wampanoag chief) was probably there to show that they had some kind of force.

Are attitudes about telling the full history of the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims changing?

Oh, absolutely. Fifty years ago, the world was not ready to embrace the story. There was absolutely no appetite to share the true history of this nation’s founding. Today, we’re in an extremely different place. People look at what we’ve done through videos, through panels and museums, through art installations. We’ve taken our history, and it’s really our shared history, and put it into a lot of different platforms for people to digest different ways. Overwhelmingly, people appreciate the story we’re telling.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

* Correction: This post previously omitted that Tisquantum traveled first to Spain and then England.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook