For Sale: A 19th-Century Silk Map of North America, Tiny Enough to Fit on a Pincushion

The cartographic curio was probably an educational tool.

Sewing needles and pins have a vexing habit of wandering away or inserting themselves into fingertips. In the 19th century, someone looking to corral her pointy supplies probably wrangled them with a pincushion. And around 1820, she may have pierced a needle through Charleston, New York, or Hudson Bay, on a diminutive, plush map of North America.

This map, printed on silk, is currently up for sale via Daniel Crouch Rare Books with an asking price of £1,800 ($2,212 in U.S. dollars). The sellers suggest that the cartographic curio—still studded with eight pins—was probably a mass-produced educational tool devised to teach Britain’s Georgian-era schoolgirls a little about the continent on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Needlepoint was a common activity for girls and women at the time, and there was a societal push to marry lessons with leisure. “There was a lot of debate about how to do primary education in the early 19th century, and much emphasis on ‘doubling up’ exercises—learn a skill and some information at the same time,” says Matthew Edney, a geographer and cartographic historian at the University of Southern Maine and the Osher Map Library.

The sellers write that pincushions were first peddled by toy shops in the 18th century, and that the map aligns with other educational games for kids that were being produced at the time, including jigsaw puzzles with cartographic designs. Grown-up customers across the economic spectrum were a little map-happy, too: Brainy, curious shoppers snapped up cartographic things tiny, twee, and portable, from itty-bitty almanacs to 18th-century pocket globes small enough to fit in an outstretched palm.

The map measures only about two inches in diameter, so a fair amount of accuracy and nuance were sacrificed for the sake of space. But a fine-grained lay of the land wasn’t the point, says Edney. Instead, this map is “part of a long tradition of ‘map fluff’ that is not interested in high detail and great accuracy, but in simply saying, ‘I’m a map!’ and in giving a broad geographical outline. As something touted for educational use, it should be simplified so as to be easily read.”

The maker of this plush map chose a few of the “most obvious” cities and geographic features on the continent, says Nick Trimming, of Daniel Crouch Rare Books. If more had been squeezed onto the map, the labels would have smashed into each other and become illegible.

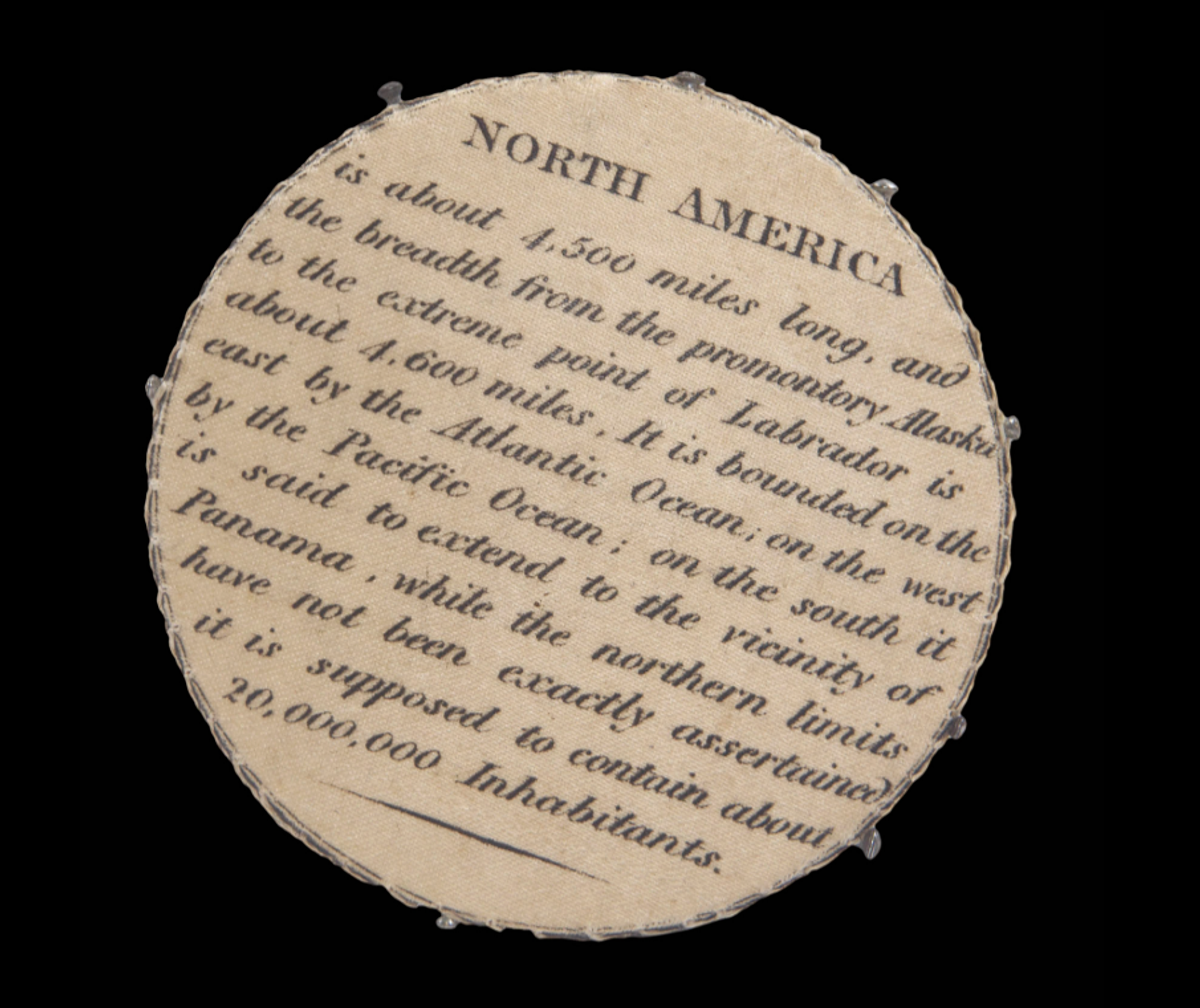

A smattering of facts about the continent are printed on the reverse side. The mapmaker, who may have been the London-based publisher and printer William Darton Jr., noted that North America “is bounded on the east by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Pacific Ocean,” and that “while the northern limits have not been exactly ascertained, it is supposed to contain about 20,000,000 Inhabitants.”

(The 1820 U.S. census counted 9,625,734 residents of the states and territories, including free white people, enslaved people, non-naturalized residents, and free people of color—a tally that included some Native Americans.)

There are obvious limits to how much one could learn about the world from one small map of a single continent—especially one that glosses over the vast majority of its features. But this small wonder is a reminder of how big the world is, and how much there is to learn about it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook