How a Mining Boom Led a Mormon Florist to Invent the Pisco Sour

The unorthodox backstory of Peru’s signature cocktail.

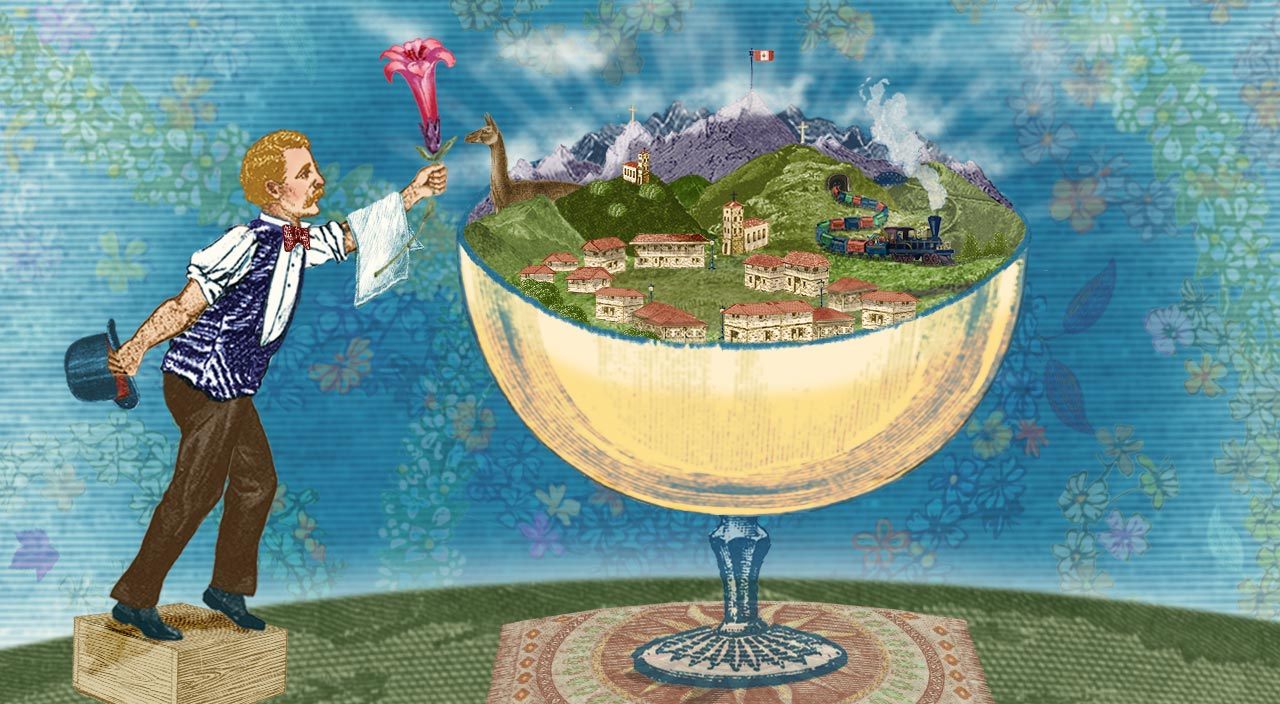

On the first Saturday of February, Peruvians raise a glass to their country’s most well-known cocktail: the Pisco Sour. Since 2003, this simple twist on the classic Whiskey Sour has had its own national holiday. But while the drink evokes a sense of pride in Peru, the Pisco Sour is largely considered the invention of an unlikely figure: a Mormon man from Salt Lake City named Victor V. Morris.

The curious path that led Morris from Utah to the Peruvian Andes began not in spirits but in flowers. Born into a large and well-respected Welsh Mormon family, Morris co-ran a floral shop with two of his brothers. But tragedy struck in 1900, when Morris’s older brother, Burton, got into a fight while on a date and was killed by two bullets through his heart. Worse, the assailant was acquitted in a high-profile case after pleading self-defense. An outraged Morris told a reporter that the legislature “should immediately repeal the law making murder an offense in Utah and thus save the State the expense of going to trial.”

After Burton’s death, Morris managed the flower shop for a few more years before selling the business to take a clerical position with a local railroad company. He may have stayed in this position and never left the United States if not for the business venture of a well-known Salt Lake City resident named A.W. McCune. A powerful figure, McCune had transformed the capital’s streetcar system from wagons to electric cars and run for both Mayor and Senate. He owned the Salt Lake Herald and half the Utah Power Company, and shortly after the turn of the century, McCune embarked on a massive Peruvian mining endeavor funded by Gilded Age robber barons including J.P. Morgan, Henry Clay Frick, and the Hearsts.

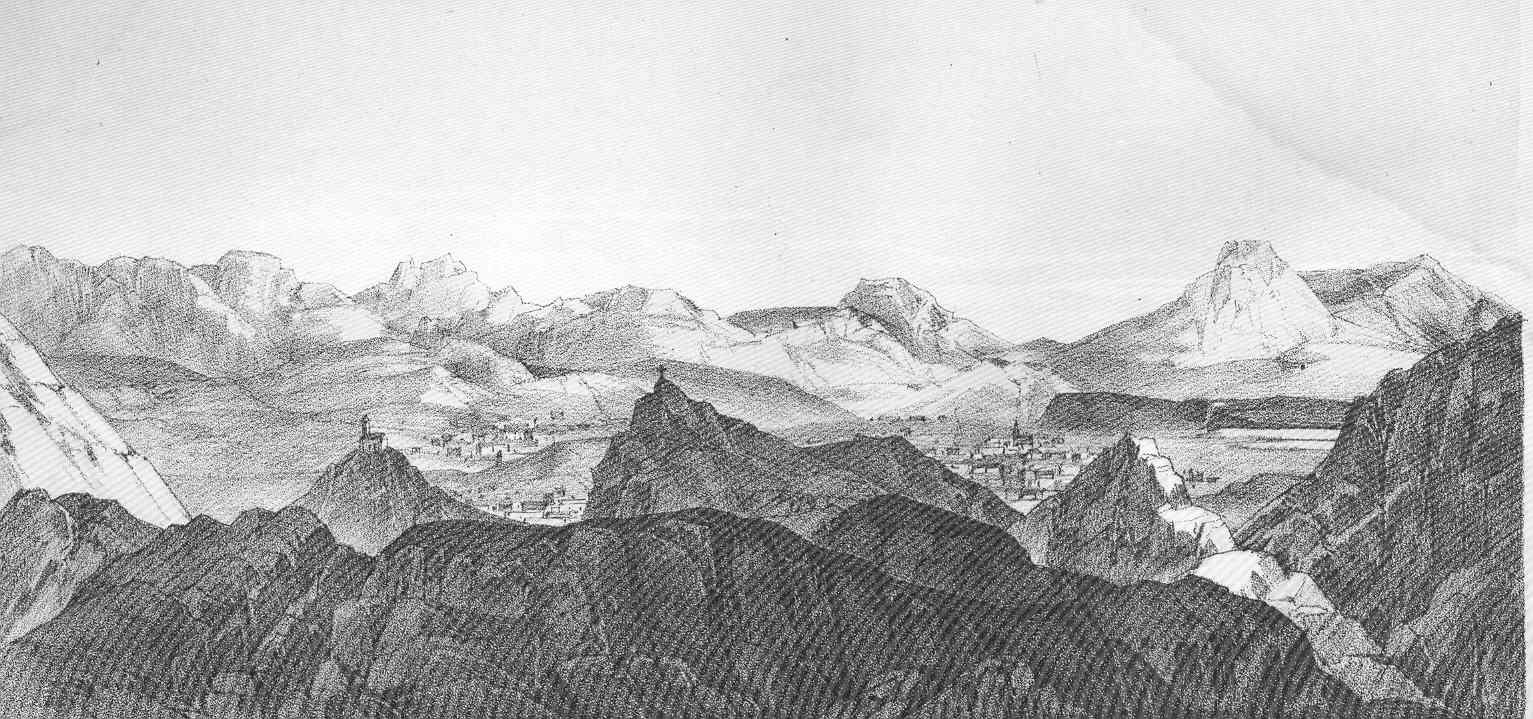

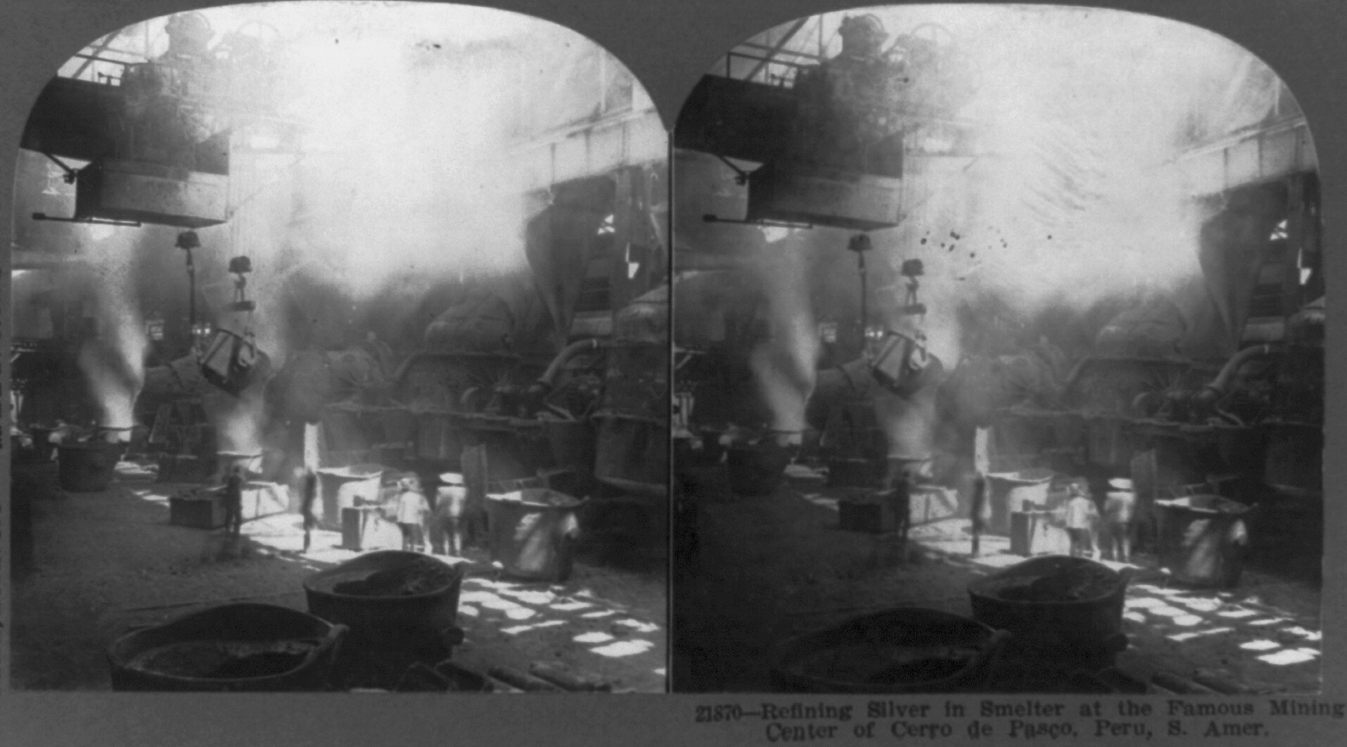

In the late 1800s, a scouting expedition led by McCune discovered old mines first excavated by Spanish colonists in the town of Cerro de Pasco. Until its liberation in 1820, the town had been a great source of riches for the Spanish. According to one local legend, the rocks around Cerro de Pasco’s campfires “wept silver.” McCune signed a mining agreement with the Peruvian government, and by 1902, McCune had broken ground. The project transformed Peru’s economy and kickstarted its mining industry. This gritty, turn of the century mining town would be the setting for the creation and popularization of Peru’s signature cocktail.

Back in Salt Lake City, residents took note of McCune’s endeavors. The city was no stranger to the mining business, which was a vital source of its growth. Many residents joined McCune’s business venture, and, in 1902, Victor V. Morris travelled to the dusty, high-altitude city of Cerro de Pasco as one of the early arrivals from Utah to join the project. There, he worked on another of McCune’s extraordinary endeavors: the construction of the world’s highest elevation railroad tracks. The railway would lead from Cerro de Pasco to La Oroya, a city with access to a port where precious metals could be shipped abroad.

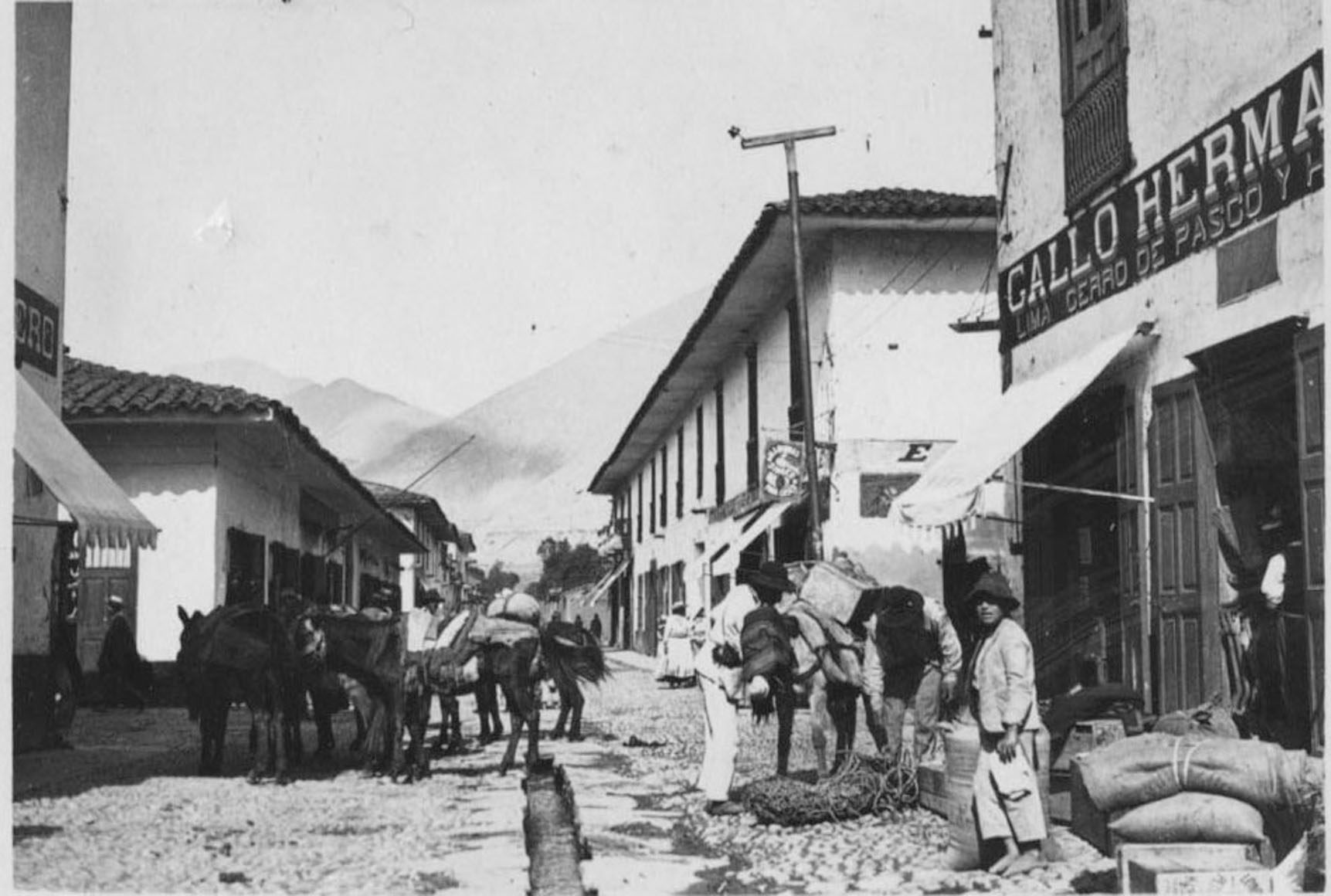

Industry transformed the dusty Andes village. By the early 1900s, Cerro de Pasco was Peru’s second largest city after Lima. Americans and other expats walked the bustling, newly drawn streets, and they both expected the latest amenities and had the mining wealth to pay for it. Soon, upscale saloons dotted the city center. These bars introduced Morris to Pisco, the yellow-colored brandy produced across Peru and Chile.

Given Mormonism’s reputation for prohibiting alcohol, the prospect of Morris enjoying the local brandy may sound like him succumbing to a boomtown’s illicit pleasures. But at the time, Salt Lake City was full of breweries, wineries, and distilleries owned and operated by members of the Mormon Church. Latter Day Saints apostle and church leader Brigham Young owned the city’s first saloon and a winery, and it wasn’t until 1921 that LDS president Heber J. Grant made teetotaling Church law—a development that aligned with the growing temperance movement across the United States. The death of Morris’s own brother was fueled by anger over poorly made mint juleps. So Morris was no stranger to saloons in Salt Lake City or Cerro de Pasco.

Peruvian oral historian Dr. José Antonio Salazar Mejia notes that this may have been where Morris discovered a traditional Peruvian drink that would serve as a prototype for the Pisco Sour. In 2012, a Peruvian Creole cookbook from 1903 was discovered with a similar recipe to the Pisco Sour, lending some evidence to this possibility.

According to Morris himself, though, it was something else that led to the Pisco Sour: a massive, all-day party. The completion of the railway was a cause of much cheer, and, in July 1904, a major celebration took place. Newspaper reports note that nearly 5,000 people attended. Women held Peruvian and American flags made of silk with gold and silver threads, and local celebrities and dignitaries joined the festivities. Morris, who oversaw the event, allegedly explained later—in a testimony to his family—that he turned to Pisco when the grand celebration ran out of whiskey for the sours being consumed.

Despite Morris’s claim, the exact year of the Pisco Sour’s birth is still contested, partly because it did not achieve widespread popularity until Morris retired to Lima with his Peruvian wife and three children, where he opened a saloon and christened it Morris’ Bar.

Located on Calle de Boza in what is now Jirón de la Unión, just a block from Plaza San Martín, Morris’ Bar quickly became a major hub of intellectual, political, and celebrity activity. By then, Morris had lost part of his leg in an accident, but it didn’t affect his demeanor. Morris was known as an affable and generous host and developed a dedicated following. Famed Peruvian writers Abraham Valdelomar, José María Eguren, and Pablo Abril de Vivero regularly scribbled their names into the guest book. As did anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber and adventurer Richard Halliburton.

Pisco Sours were the signature drink. Famed American aviator and soldier of fortune Dean Ivan Lamb noted the strength of the drink in his memoir The Incurable Filibuster, writing: “In Morris’ Bar I ordered a pisco sour. It tasted like a pleasant soft drink and I ordered another, to which the bartender objected, informing me that one was usually sufficient. After an argument he made another—from that time events were not very clear … ”

By the 1920s, some of Morris’s bartenders had taken the Pisco Sour recipe to other Lima bars. This both spread the drink and changed it, adding to the difficulty in identifying who exactly “invented” the Pisco Sour. If anything, it was more of a collaborative effort. Notably, Mario Bruiget, a one-time employee of Morris’ Bar, brought the drink to the Grand Hotel Maury, where it’s believed he added egg white and bitters. Today, this is the style most commonly served in Peru. The Grand Hotel Maury, which is still in operation, claims to be the original site of the modern Pisco Sour.

Victor V. Morris passed away in 1929, and his bar shut down that same year. As a testament to Morris’s contribution to modern Peruvian culture and the country he called home for more than half his life, a bust stands of him now in Parque de Amistad, in Lima’s Surco district.

After Morris’s passing, the drink only grew in popularity. By the 1930s, it had reached San Francisco, and the drink was a popular oddity in New York City by the 1960s. In Lima, the drink became the signature cocktail of high-end hotel bars—Orson Welles and Ernest Hemingway enjoyed the drink when in Peru. A popular legend from the Gran Hotel Bolivar describes a barefoot Ava Gardner dancing around the hotel bar after one too many Pisco Sours before being carried to her room by John Wayne himself.

Today, the drink is not just for the elite, but a Peruvian staple. And while the drink may have been popularized by an American, one thing is for sure: The Pisco Sour is fully Peruvian now.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook