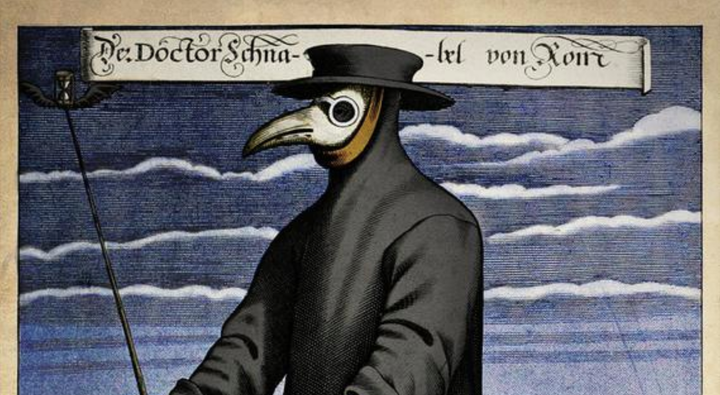

European Plague Doctor Garb Was Black, Beaked, and Very Bleak

These haunting uniforms make today’s masks look tame.

Four hundred years ago, dark figures with blanched white beaks stalked the streets of Europe. But these were no boogeymen. They were healers, dolled up to stave off the disease du jour: the bubonic plague.

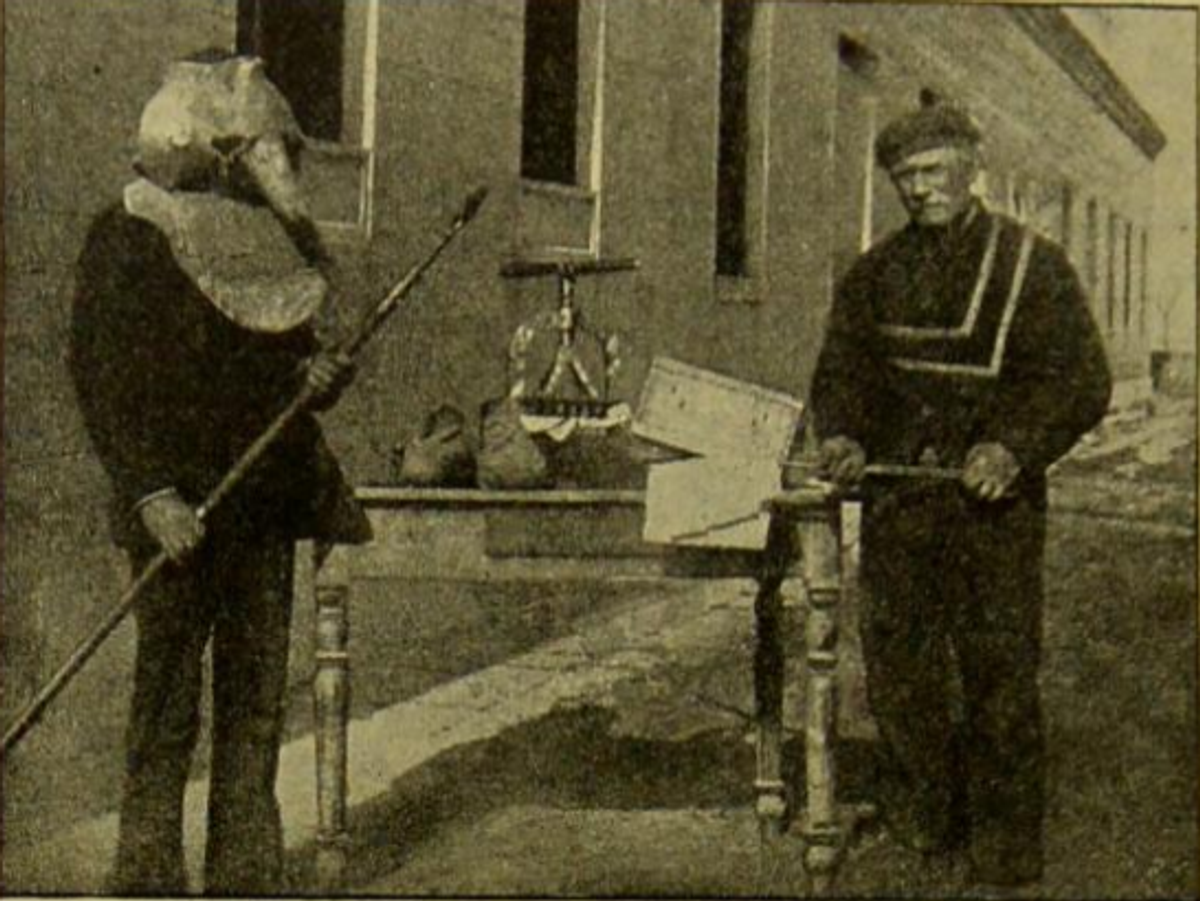

Though plagues were nothing new at the time—bacterial outbreaks were routine in medieval Europe—the outfit was a morbidly chic addition to doctors’ protective arsenal. Today, plague-doctor uniforms—worn for centuries both by actual medical professionals and empirics, who were enlisted to help combat infectious diseases despite not having graduated from med school—remain an iconic reminder of how alienating illness can be as isolation takes hold, born of an imperceptible contagion.

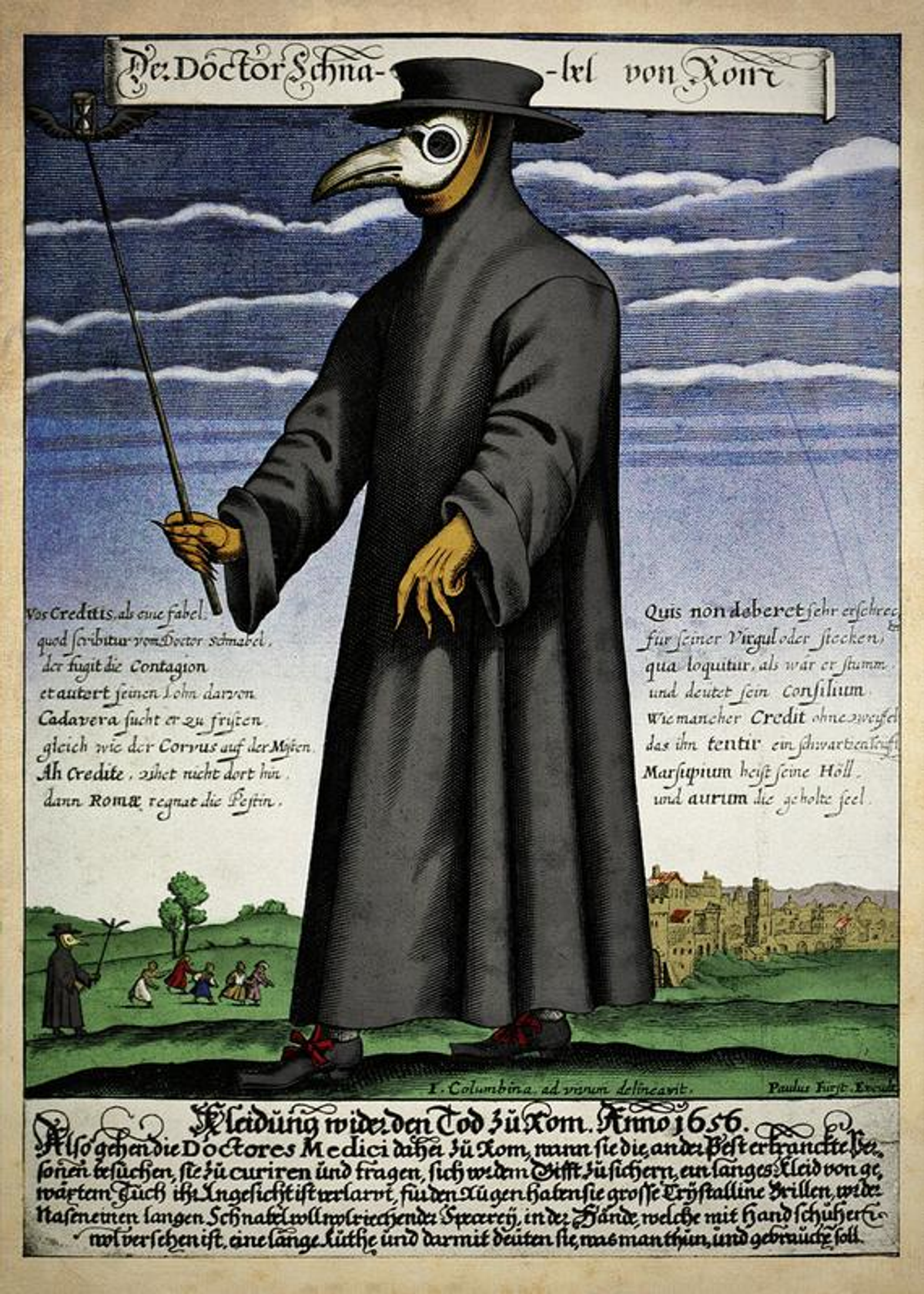

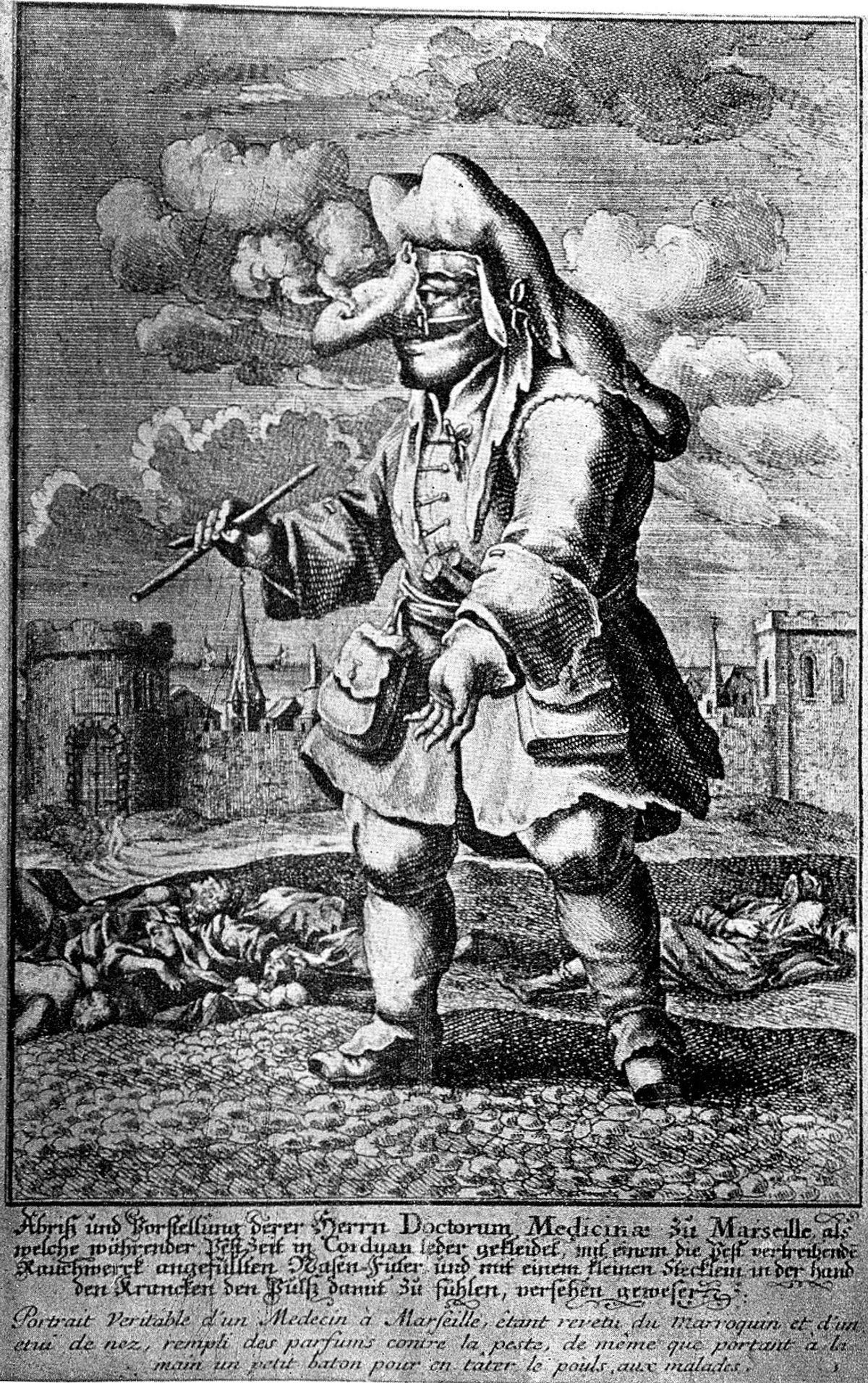

The uniform is typically attributed to Charles de Lorme, a chief physician to several French kings, who around 1630 proposed the need for such wear to keep health workers safe from disease. It consisted of a thick black overcoat, gloves, circular glass to seal the eyes behind the mask, and often a wand, to inspect patients from a distance (and, when necessary, to fend them off as well).

Plague doctors also donned off-white leather masks that ended in a conical beak—like storks who’d spent the morning delivering a baby to a doorstep, and the afternoon haunting a funeral.

The beak was a vital component of the miasma theory—the long-since-disproven notion that held that diseases could spread through their stink. (Needless to say, rotting corpses from the Black Death, covered with pustules, had a ferocious odor, so masks thicker than an N95 were in high demand.) Plague doctors kept their masks stuffed with powerfully scented spices and herbs such as mint or lavender, to keep the stench of pestilence out of their noses.

Herewith are several timely depictions of these early, eerie health-care workers, wearing a costume that dominated plague epidemics up through the 19th century.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook