How the Black Death Gave Rise to British Pub Culture

For centuries-old bars, a pandemic is nothing new.

“I’ll buy you a beer when this is all over,” declares Christo Tofalli, the landlord of Ye Olde Fighting Cocks, which lays claim to the contentious title of Britain’s oldest pub and is no stranger to pandemics. While closed, Ye Olde Fighting Cocks, in the historic city of Saint Albans, has become a Community Supply Point, providing much-needed groceries and offering free delivery to the elderly. They are even delivering Sunday Roast dinners to residents in lockdown. The threat posed by coronavirus may feel unprecedented, but Tofalli, who manages the pub, says he has been looking to the past for inspiration.

In the summer of 1348, which was some hard-to-specify number of centuries after Ye Olde Fighting Cocks served its first beer, the Black Death appeared on the southern shores of England. By the end of 1349, millions lay dead, victims of what medieval historian Norman Cantor describes unflinchingly in In the Wake of Plague as “the greatest biomedical disaster in European and possibly in world history.”

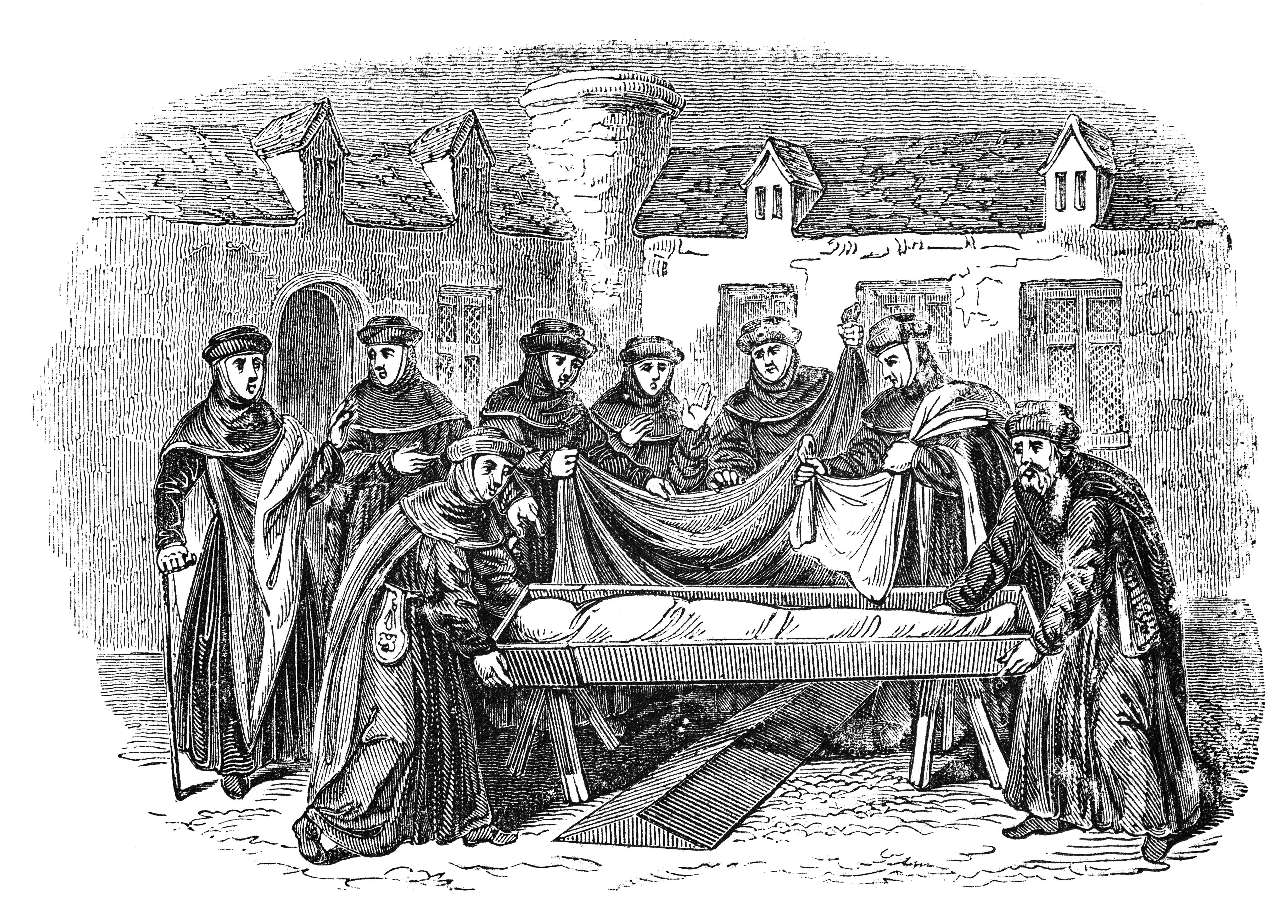

Medieval society could muster little response, Cantor writes, except to “Pray very hard, quarantine the sick, run away, or find a scapegoat to blame for the terror.” Nobility and wealth was no defense: Princess Joan of England was struck down on her way to marry in Spain, while the newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury perished shortly after being ordained by the Pope. The plague even halted (temporarily) the perpetual conflict between the French and English.

This pestilence returned repeatedly too; Cantor writes that “there were at least three waves of the Black Death falling upon England over the century following 1350.”

According to historian Robert Tombs, author of The English and Their History, one of the many repercussions was especially pertinent to establishments like Ye Olde Fighting Cocks: the rise of pub culture in England.

When the plague arrived in 1348, drinking beer was already a fundamental component of Englishness. In his tome, Tombs writes that the English fighting the Norman invaders at Hastings in 1066 were suffering from hangovers. Drinking was even enshrined into the Magna Carta of 1215, which “called for uniform measures of ale.”

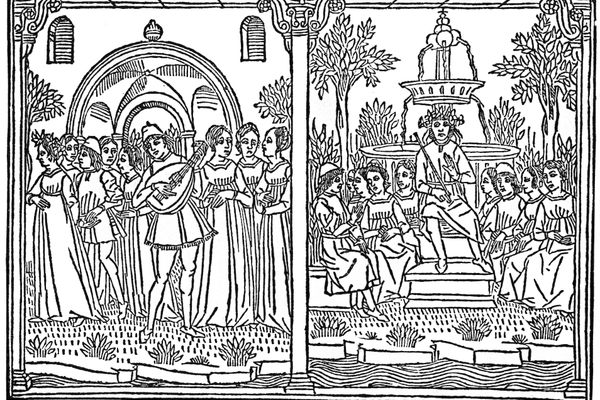

Drinking pre-Black Death, though, was comparably amateurish. In Man Walks Into a Pub: A Sociable History of Beer, beer journalist Pete Brown writes that “Society revolved around popular celebrations known as ‘ales’: bride-ales, church-ales … were gatherings where plenty of alcohol was drunk, and they frequently degenerated into mayhem.” Anyone could brew up a batch of ale in their home, and standards and strengths varied wildly. Homebrewed ale was advertised with “an ale stake,” Brown adds, which consisted of “a pole covered with some kind of foliage above the door.”

By the 1370s, though, the Black Death had caused a critical labor shortage, the stark consequence of some 50 percent of the population perishing in the plague. Eventually, this proved a boon for the peasantry of England, who could command higher wages for their work and achieve higher standards of living. As a result, the alehouses that were simply households selling or giving away leftover ale were replaced by more commercialized, permanent establishments set up by the best brewers and offering better food.

“The survivors [of the Black Death] prioritized expenditure on foodstuffs, clothing, fuel, and domestic utensils,” writes Professor Mark Bailey of the University of East Anglia, who also credits the plague for the rise of pub culture, over email. “They drank more and better quality ale; ate more and better quality bread; and consumed more meat and dairy produce. Alongside this increased disposable income, they also had more leisure time.”

Not every establishment looked like a modern pub: Alehouses were often still literally brewers’ homes, inns offered ale and accommodation, and taverns were a sort of medieval wine bar, a lasting legacy of the Roman Taberna.

In spirit, though, the pub was there. Peasants had the time and money for better food, drink, and leisure. “More ale was drunk, and beer (with hops) was introduced from the Low Countries. Brewing became more commercialized, with taverns and alehouses for drinking and playing games,” writes Tombs. “The English pub was born.”

Over time, parts of all three combined into the idea of the “public house,” regulated by authorities. In place of the simple ale stake, Brown writes, Richard II made it mandatory to erect a sign. “Gradually, commercial brewers started to build bigger houses that became busy meeting places, hence the term ‘public house’ … If you look at pubs today, you can see the community aspect that is the legacy of the alehouse, the architecture and sense of national heritage of the inn, and the tavern tradition of spending the evening with your peers getting slowly rat-arsed and talking about nothing with increasing conviction as the night wears on.”

This communal legacy can be felt in the food deliveries keeping the staff of Ye Olde Fighting Cocks busy today. “Booze and food have been on offer here through the centuries,” says Tofalli, “even in times of war, panic, and disease.” Other traditional pubs, which face similar stresses of having to stay closed and pay rent, without knowing when they can fully re-open, are hosting virtual trivia nights and staying involved in people’s lives in other ways.

For Brits, a pub has always been more than just a place that sells beer, and the threat of closure is keenly felt for reasons beyond having a drink. “This goes beyond heritage,” Tofalli says, “it goes right into the core of our society.” For Brown, “The pub itself defines this country, remaining a focal point for our social lives even among nondrinkers.”

But even a millennium of longevity can’t provide any certainty. “No one really knows what’s going to happen,” says Tofalli. “We can just put our best foot forward, do the right thing.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook