The Discovery Tree’s Destruction Launched the Modern Conservation Movement

A giant sequoia—the largest type of tree on Earth—was sold for parts in 1853. Now we have art and environmental policies in its image.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

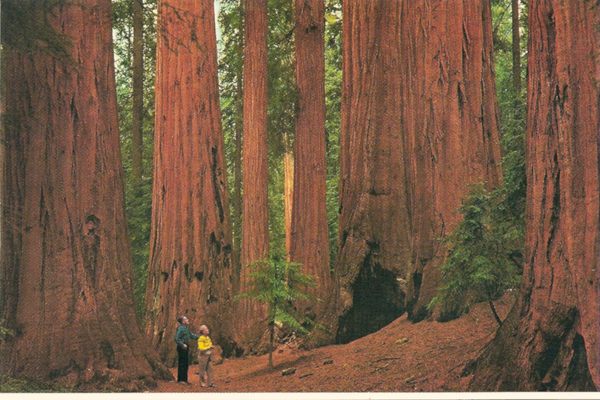

Amanda McGowan: It’s 1852 in the forests of Northern California. A long-haired big-game hunter named Augustus T. Dowd is stumbling through the trees. He’s tracking a wounded grizzly bear, following a trail of bloody prints. Crashing through the brush, Dowd stumbles on something that stops him in his tracks. It’s a grove, a cluster of trees. But these trees are unlike any that Dowd has ever seen. They’re giants. They tower hundreds and hundreds of feet into the air. It would take ten men with arms spread wide to encircle one of the trunks. And then Dowd sees the biggest tree of them all, 30 feet wide and 300 feet tall.

I’m Amanda McGowan and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today we’ll learn about the life and death of the largest tree in this grove, known as the Discovery Tree. Its journey from tourist attraction to sparking a conservation movement after this.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Josh Winkler: Well, so I went out on a spring break in March and it was kind of wintry.

Amanda: In 2014, 160 years after the big-game hunter Augustus T. Dowd stumbled on a grove of giant trees, artist Josh Winkler arrived at the very same grove, the Calaveras Big Tree Grove in Arnold, California.

Josh: I just brought a bunch of different papers and I brought a bunch of different types of graphite from just soft graphite pencils to chunks of graphite.

Amanda: Josh was looking for the biggest tree in the grove, the one that had so fascinated Augustus T. Dowd: the Discovery Tree, as it came to be known. The Discovery Tree is a giant sequoia, a kind of enormous ancient tree species that’s found naturally only in California. Like its cousin, the coastal redwood, giant sequoias can grow to hundreds of feet high and live for over a thousand years. Sequoias are a little bit shorter and stouter than redwoods. They have thicker trunks. But really just the scale and size of these things is hard to convey.

Josh: You just can’t believe it. Like the age, the immensity, the fact that the trees seem like they’re from a different time that doesn’t exist anymore. I mean, you picture a time when there’s giant animals and, you know, they’re prehistoric.

Amanda: And the Discovery Tree is distinct even by giant sequoia standards. Josh was interested in this tree in particular because of what happened to it after Augustus T. Dowd found it.

Josh: But what’s really striking is, you know, it’s just a giant stump. There’s a set of stairs that walk up to the top of it. It’s probably six or seven steps that you go up to to get on top of this thing. I’d say it’s probably six, seven feet tall from the ground. So visitors can go up and get on top of the stump.

Amanda: Yeah, the Discovery Tree today is just the Discovery Stump. In a way, the tree’s destruction was set into motion the very moment Dowd first laid eyes on it. Native Americans had long known of the existence of these giant trees and lived sustainably among them for centuries. But once European Americans started arriving around the time of the gold rush, it was a totally different story. News of Dowd’s “discovery” spread, and soon entrepreneurs realized they could make some serious cash off of the disbelief and wonder that these trees inspired. In 1853, about a year after Dowd first came across the Discovery Tree, two businessmen brothers named the Lapham brothers made a land claim on the grove. At this time in California, there were all kinds of dubious land grabs, and you could say this was one of them. They brought in a friend who was the head of a local water company. His name was William Hanford, and they set out to dismantle the tree and turn it into a tourist attraction. First, Hanford and his men stripped the bark off of the tree in these giant 40-foot-tall sections, and then they set about cutting it down.

Josh: They had these augers, these big long corkscrews, and they just augered into this tree about 10 feet up from the ground and just kept going into it all the way around the tree.

Amanda: But the tree didn’t budge. I mean, this thing was like rock solid. Remember, it was almost 30 feet wide.

Josh: And it took a few days and a windstorm to actually knock it down because it was so stable.

Amanda: Once it was finally severed, the Lapham brothers made sure that the stump became a moneymaker. They opened a hotel on the site and sold souvenirs made out of the tree, like this They opened a hotel on the site and sold souvenirs made out of the tree, like cups from its wood and pin cushions made out of its bark. They even had a piece of the fallen trunk made into a bowling alley. The top of the stump was leveled so that it could be used to host lectures and concerts, even dances. Around 40 people could comfortably fit on top.

Josh: There are old paintings where you can see, you know, people in their Sunday dress out there dancing on the stump. Lots of people have been married on it.

Amanda: Meanwhile, Hanford took that bark that he had stripped off and sent it on a journey of its own. He shipped it in pieces to San Francisco, where it was reassembled in the shape of a hollow room that visitors could pay to go inside, complete with carpeting and a piano. Admission was 50 cents. From there, the bark traveled on to New York City. Hanford was actually in negotiations with P.T. Barnum to have it included in his sideshows, but at some point the talks went south and Hanford opened his own kind of sideshow on Broadway. Visitors were skeptical that the tree could possibly be legit. The New York Times reported, “We have no assurance from seeing this clothed skeleton that the tree was actually so large.” And the bark might have gone on to other cities too, but it was burned up in a warehouse fire in New York in 1855. Not everybody was thrilled by the prospect of sitting inside a tree room or dancing on the stump of a felled sequoia. In the popular press, outrage started to spread about the treatment of the Discovery Tree and other giant trees that were in its grove. One of the most widely read magazines of the day was called the Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion. And in October of 1853, they wrote about this, saying, “To our minds, it seems a cruel idea, a perfect desecration, to cut down such a splendid tree.” Elsewhere, the destruction was called barbarous. Stripping the bark was compared to jackals stripping the bark was compared to jackals stripping the carcass of a dead lion. Others called for California’s giant trees to be protected by the state or federal government. A famous writer and naturalist of the day named John Muir also commented on this. He later went on to be a founder of the Sierra Club.

Josh: He has this famous quote where he says, “They cut down the tree and then the vandals danced upon the stump.”

Amanda: Historians say that the attention these trees got was an early moment where Americans were thinking about protecting natural spaces from the worst impulses of business. And the sentiment grew to the extent that by 1864, California Senator John Conness introduced a bill in Congress to protect a different area of the state, the Yosemite Valley. In a speech, Conness said, “The necessity of taking early possession and care of these great wonders can easily be seen and understood.” The bill to protect Yosemite was passed. As a result, tracts of Yosemite Valley were transferred over to the state of California for protection, becoming America’s very first state park. It was an early forerunner of what would later become, in subsequent decades, the national park system.

Josh: And so it’s this story about exploitation, which I think is emblematic of so much stuff that happened, you know, across the American landscape. But there’s also this element of hope because it helped start organizations that protected more sequoias. So the fact that this tree was cut down and some other trees in the Grove were exploited brought people an awareness to protect more trees and more groves.

Amanda: When Josh Winkler arrived at the Grove, he knew he wanted to create a work of art that would convey the size and the scale and the majesty of the Discovery Tree and share it with the world, which in some ways was not so different from the early entrepreneurs who first descended on it, right? But Josh approached this in a radically different way. I mean, yeah, all he had to work with was a large stump. But beyond that, he didn’t want to disturb or destroy the tree any more than it already had been. So he decided to take rubbings of the surface of the stump.

Josh: They allowed me to set up a little tent really close. So I was just able to sleep right there, you know, and I’d get up early, drink coffee and just start working. Every day for about 10 days, Josh would climb the steps to the top of the discovery stump and unroll giant sheets of paper, 25 feet long and four feet wide. Working in sections, he would get on his hands and knees and with a graphite pencil, he’d rub over every indent and bump in the stump surface. The resulting rubbings are extremely detailed.

Josh: You can still see the rings of its age in the surface. You can see the names of tourists that are carved in the stump. There’s a geologic marker pounded into the surface, which is in the rubbing. You can also see burn scars, which is really kind of amazing. And so the stump as a whole, the rubbing of it, it almost looks like a map, like this geographic topography.

Amanda: And just like the bark of the Discovery Tree, this rubbing has traveled all over. It’s been exhibited in Minnesota and Nebraska and the Yukon territory. It’s been shared with the world and it’s also left the stump intact. You can visit the discovery stump today. It’s at the Calaveras Big Tree State Park in Arnold, California. Actually, two of Josh’s smaller rubbings of the tree are at the site, though he says that he’s still looking for a permanent home for the entire Discovery Tree rubbing. If there’s any museums or institutions listening, we will link to Josh’s page as well as some other great articles and books about the Discovery Tree. Special thanks to Josh Winkler and to Martin Huberty of the Calaveras Visitors Bureau for telling me about the Discovery Tree.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Witness Docs. The production team includes Dylan Thuras, Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Willis Ryder Arnold, Sarah Wyman, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire Ceus, Gabby Gladney, Gianna Palmer, Tracy Samuelson, John DeLore. Our technical director is Casey Holford. This episode was sound designed and mixed by Luz Fleming.

If you would like to learn more, you can visit us online at atlasobscura.com. Our theme and end credit music is by Sam Tindall, and I’m Amanda McGowan wishing you all the wonder in the world. I’ll see you next time.

This story originally ran in 2023; it has been updated for 2025.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook