In India, the British Hyped Potatoes to Justify Colonialism

The British East India Company handed out seeds and bribes to farmers willing to grow the humble spud.

It’s hard to imagine what regional cuisines across India would look like without the potato. Many of the most iconic dishes found on Indian plates, such as Bengal’s aloo posto or South India’s masala dosa are filled with the starchy vegetable. But the potato is indigenous to South America, not South Asia. Colonialism, as well as Enlightenment theories on happiness, led to the tuber becoming an important ingredient in Indian cooking.

Yet the potato was an unlikely candidate for a starring role in Indian food. When the British East India Company arrived in India in the 17th century, they found that, although the Portuguese had brought the crop over earlier, very few Indians grew or ate potatoes. Moreover, many Company agents thought the climate was too hot, too windy, and too dry to successfully grow the rain-loving tuber. Nevertheless, the East India Company decided to heavily promote the potato among Indian peasants.

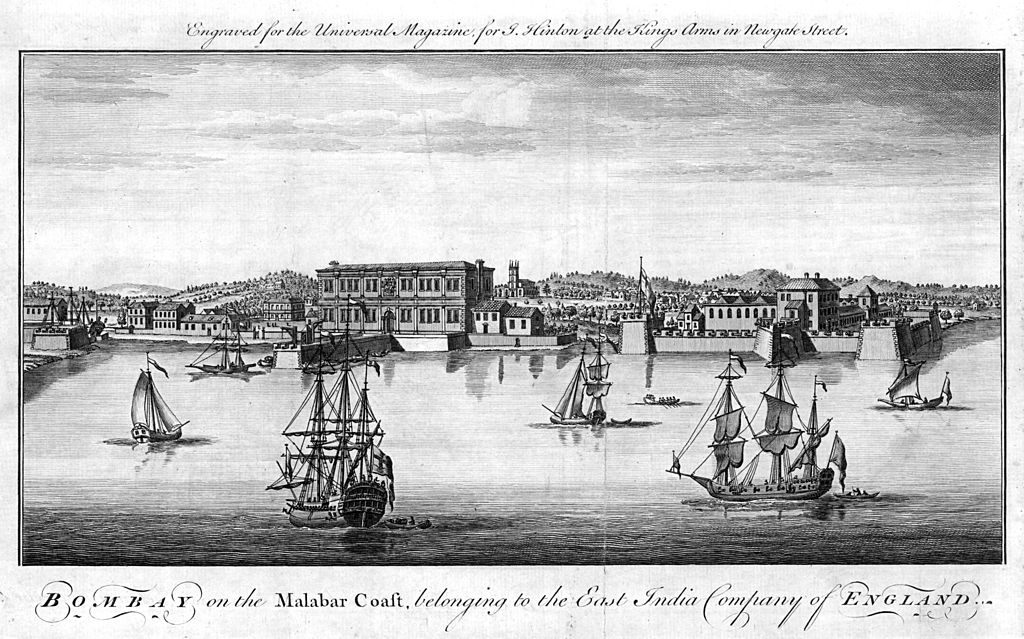

According to 1797 Company ledgers, now housed in the India Office Records in the British Library, agents in Bengal provided a “considerable quantity” of free seeds to peasants to encourage them to produce and eat their crop. In Bombay, the East India Company exempted potatoes from the transit taxes typically levied on the crop in order to encourage their cultivation. The Company also provided 100 rupees, a significant sum at the time, to be distributed amongst potato-growing peasants to reward them.

In Madras, a potato campaign also began in 1797. It was spearheaded by one man: Dr. Benjamin Heyne, a Scottish missionary and naturalist. In a 1799 letter, he wrote of his desire to use potatoes to prevent the “lamentable effects which have too often been produced by a scarcity of grain” in India. In order to promote the crop, he bribed Indian peasants with approximately one-third of a rupee to plant potatoes. Furthermore, to show Indian peasants the value of the crop, he planted potatoes in the Bangalore Botanical Gardens, and traveled far and wide across the subcontinent promoting the tuber in various villages. Soon, societies sprung up around India seeking to promote various crops, especially the potato. The Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India, formed in Calcutta in 1820, held contests for growing the “best” potato. Though records are unclear on exactly what qualifications they were looking for, winners were awarded 40 rupees and a silver medal.

The British were obsessed with promoting the potato in India, despite the allegedly inhospitable climate. Yet their relentless promotion of the tuber had a sinister underpinning. In the 18th century, the potato gripped the imaginations of political and economic leaders alike. Adam Smith, in his famous economic treatise Wealth of Nations, waxed rhapsodic about the potato for four paragraphs, writing that “the strongest men and the most beautiful women” in the British Dominions were the potato-eating Irish. “Should this root ever become in any part of Europe, like rice in some rice countries, the common and favourite vegetable food of the people,” Smith predicted, “the same quantity of cultivated land would maintain a much greater number of people.” He advocated that all laborers should be fed potatoes. Others, like the famous Scottish doctor William Buchan, spoke of the fact that “some of the stoutest men we know, are brought up on milk and potatoes.”

The East India Company officials took these Enlightenment visions to heart. As one colonial official wrote in a 1789 letter, the potato was a “substantial provision for the Labourer,” which would help “improve and extend materials for foreign trade.” The potato, for the British, represented a tool through which they could expand their corps of colonial laborers, spanning the globe from Belfast to Bombay.

But the potato was not only understood as a means to increase Britain’s wealth. It was also envisioned as a justification for British imperialism. The Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India, in their 1838 records of transactions, stated that through growing European-introduced crops such as the potato, “happiness till now unknown in India, will be diffused abroad.” The East India Company too promoted the idea that the potato was an embodiment of “happiness,” noting in an 1800 report by the Bengal Revenue Commission that the tuber would help “alleviate the Miseries” in India caused by the frequent failures of the rice crop. Food historian Rebecca Earle writes that the ruling elite at the time understood public happiness as the “highest aim of government.” The potato as a tool to increase public happiness meant it embodied Britain’s supposed right—and by extension moral imperative—to rule India.

Despite the original doubts of British East India Company agents, the promotion of the potato did in fact bring the tuber into widespread cultivation. While the East India Company assumed the climate of India would be inhospitable, certain zones on the vast subcontinent are well-suited to nurturing the crop. According to food writer and historian Chitrita Banerji, the “great virtue of the potato is its flexibility in how it could be cooked, and that it was not difficult to cultivate.” The crop’s similarity to many indigenous gourds, as well as the fact that its consumption was not prohibited by any religious traditions, ended up easing the potato’s entrance into different regional Indian cuisines.

It wasn’t long before the relentless promotion had an effect. In an 1814 letter, a British army wife wrote in the typical patronizing colonial parlance that “the natives are all fond of it, and eat it without scruple.” Cookbooks written in Hindi and Gujarati in the 19th century give recipes for everything from fried potatoes to potato khichari, a traditional dish of rice and lentils. The potato transformed Indian cuisine, with the creation of many much-loved potato dishes.

Yet the potato never reshaped Indian diets in the ways the British intended. The British imagined that the potato would be a staple in India, just as it was for the Irish. But the potato never displaced rice as India’s staple crop. “India is the great assimilator,” Banerji says. The potato, she argues, was cooked in place of Indian crops such as yams and gourds rather than as a substitute for rice. Now, Banerji says with a laugh, Indian is one of the only cuisines where two starches, potatoes and rice, often feature in the same meal.

While much of India has welcomed the potato with open arms, its foreign origins have not been forgotten in certain corners of the country. At Jagannath Temple in Puri, a sacred Hindu worship space, food is offered up to the deity Jagannath six times a day. The potato, however, isn’t present in any of those dishes. “These temples have been making the same food for the past 500 years,” Banerji says. That means rice and dal, among other dishes. “Since the potato has not been around that long, it is not served.”

Yet for most people, the potato is standard fare in India. Banerji recalls with reverence the potatoes she grew up eating. “Oh! I can never make those potatoes as good as my mother,” she says, describing her steamed potatoes with turmeric, mustard oil, ground chili, salt, and asafetida. From Lucknow to Delhi, Goa to Pune, the potato is served in many different ways on Indian plates today. “It is always funny to me,” Banerji says with a knowing smile, “that colonialism’s injustices provoked these culinary delights.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook