The Victorian Belief That a Train Ride Could Cause Instant Insanity

“Railway madmen” were thought to be activated by the sounds and motion of train travel.

January, 1865. The peace on a regular English train journey from Carnforth to Liverpool is shattered by one man’s deranged laughter and erratic antics. Armed with a gun and attacking the windows to get to the other increasingly frightened passengers, he seems out of control. At the next train stop in Lancaster, the man suddenly becomes calm and serenity is returned. But as the train begins to roll again, his aggression returns . The motion of the train becomes the only means to gauge the man’s behavior. His mood changes from one stop to the next, twisting and turning with the carriage.

The railway passenger prancing around with a pistol was by no means the strangest case of “railway madness” reported during the Victorian era in Britain. There seemed to be something about the railways that made people—particularly men—suffer mental anguish and unrest.

As the railway grew more popular in the 1850s and 1860s, trains allowed travelers to move about with unprecedented speed and efficiency, cutting the length of travel time drastically. But according to the more fearful Victorians, these technological achievements came at the considerable cost of mental health. As Edwin Fuller Torrey and Judy Miller wrote in The Invisible Plague: The Rise of Mental Illness from 1750 to the Present, trains were believed to “injure the brain.” In particular, the jarring motion of the train was alleged to unhinge the mind and either drive sane people mad or trigger violent outbursts from a latent “lunatic.” Mixed with the noise of the train car, it could, it was believed, shatter nerves.

In the 1860s and ‘70s, reports began emerging of bizarre passenger behavior on the railways. When seemingly sedate people boarded trains, they suddenly began behaving in socially unacceptable ways. One Scottish aristocrat was reported to have ditched his clothes aboard a train before “leaning out the window” ranting and raving. After he left the train, he suddenly recovered his composure.

Regarding the specific type of mental condition believed to have been caused by the trains, Professor Amy-Milne Smith, a cultural historian at Wilfrid Laurier University, notes that “railway madmen would have all likely be seen as suffering mania.” Medical journals at the time were very concerned about how railway madmen could be detected when their madness might lie latent.

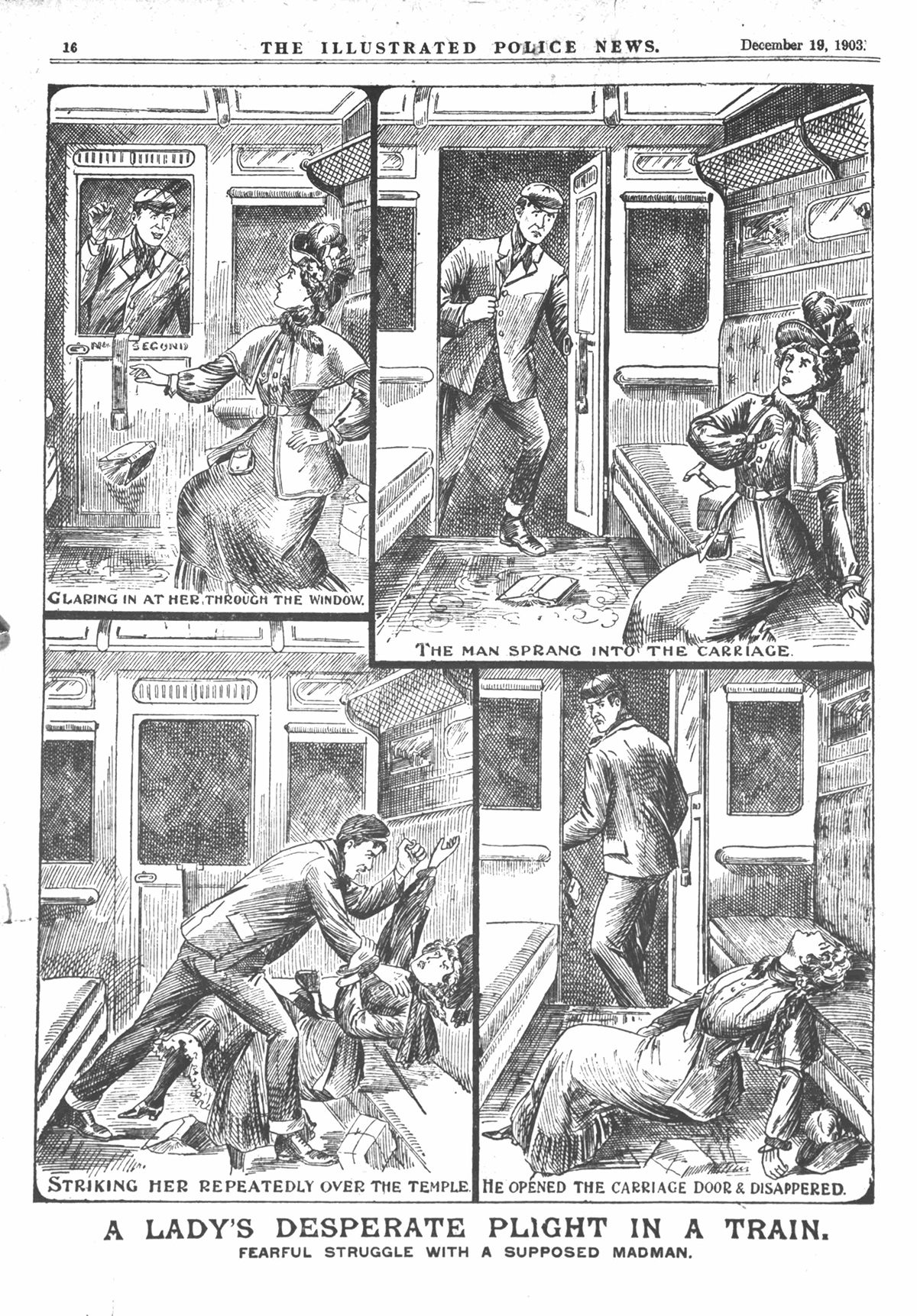

Not all goings-on in the first- and second-class carriages involved eccentric rambling in the nude—vicious attacks with knives and other weapons that could result in death were reported as well. The trains themselves were considered to be ridden with perilous conditions that endangered passengers. Confined carriages were locked for privacy reasons, meaning people were at risk of being trapped in small rooms with “lunatics” who were ready to snap at any minute. The lack of suitable on-board communications meant that if attacked by such a person, you couldn’t easily call for help.

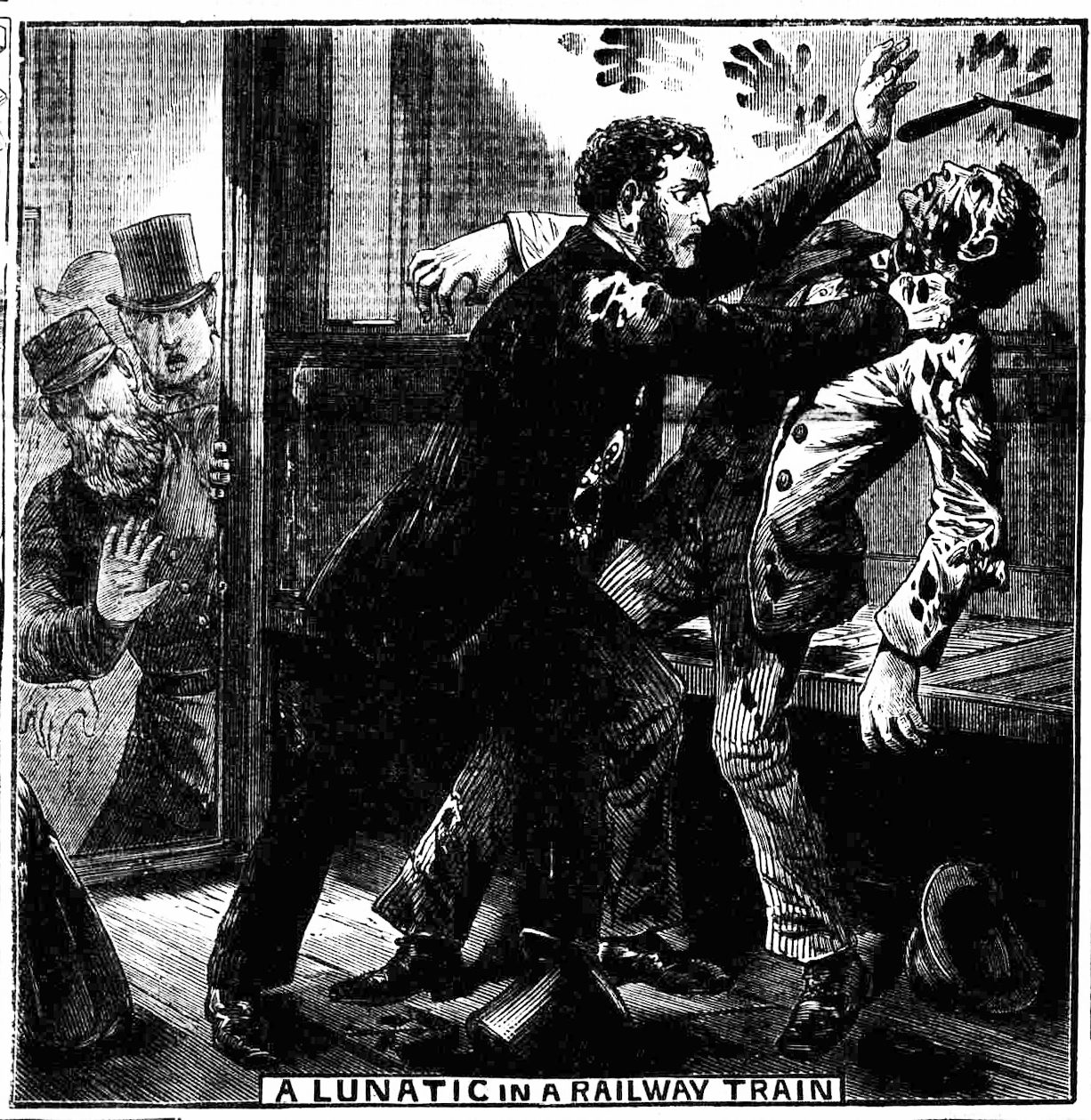

The media did its part to whip up a frenzy over railway madness. One 1864 story, starkly titled “A Madman in a Railway Carriage,” gleefully related how a burly sailor became incensed, flailing around in an erratic manner first trying to climb out of the window , and then swearing and shouting at the other occupants of the carriage and struggling with everyone . A superhuman strength gripped this aggressor and four people were required to restrain him and he had to be bound to a seat. The conflict was not over yet though. When the sailor was released, he charged viciously at those who had restrained him and accusing them of stealing from him, it took railway officials and finally the police to subdue and arrest the sailor.

The problem of railway madness did not just refer to those driven insane in the process of the journey. Another concern of the time was that the railway provided a swift and convenient getaway for patients who had escaped from the various mental-health institutions throughout Great Britain.

In 1845, Punch magazine published a cartoon showing train tracks leading to an asylum. The logistics of the railways dotted around the countryside meant that a “mental patient” could evade the staff and hop on the next train to freedom. Stories of maniacs and terror on the tracks terrified many and delighted others.

As Professor Anna Despotopoulou at the University of Athens says, “the train in the 19th century offered women an unprecedented opportunity to travel freely” but stories of madmen on the rails “often heightened the anxiety to travel.” After going on a particular train ride, female novelist George Eliot stated with tongue firmly in cheek that upon seeing someone who looked wild and brutish, she was reminded of “all the horrible stories of madmen in railways.” Elliot seemed to relish the excitement of a possible confrontation and sounded rather disappointed when the figure turned out to be an ordinary clergyman.

Other members of the elite were more frightened than Eliot of the potential for being in a compartment with a maniac. However, there was no easy solution because of the trains’ design, which encouraged the form of physical isolation that increased fears of these fabled madmen.

It was nevertheless agreed that something had to be done to protect passengers against railway maniacs. Attacks, according to the Scotsman newspaper, were becoming an everyday occurrence, and railway madness on British trains had become internationally renowned. One “American Traveller” spoke of carrying a loaded revolver on trains in England because of the prospect of encounters with a “madman.”

The 1864 by-laws of the Victorian Railways stipulated that “insane persons” should be isolated “in a compartment by themselves.” If railway madmen could not be stopped then they might at least be contained. These regulations, of course, ignored those who boarded the train perfectly in control of their faculties and only displayed their erratic behavior once the train was in motion and the doors locked.

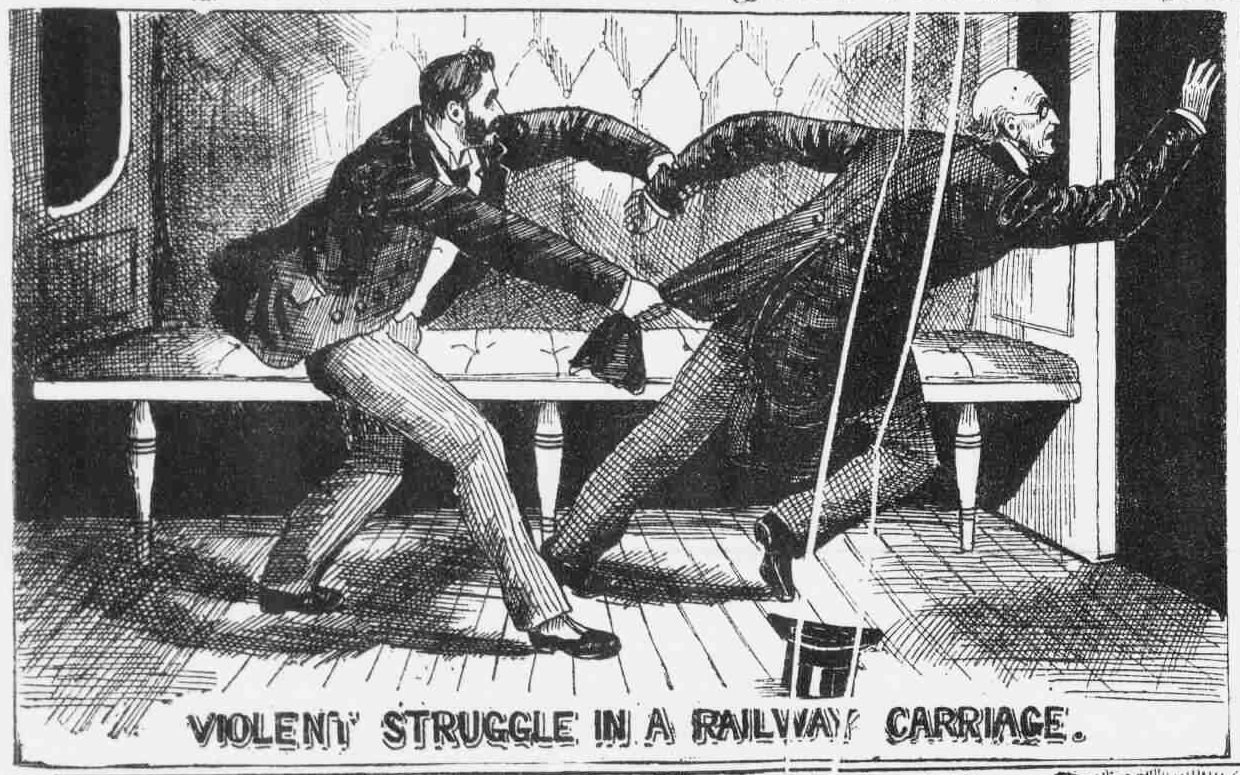

Implementing these rules was a problem. Every time an invention was proposed to ensure greater safety, it was rejected on the grounds of protecting personal space. Case in point: “Müller’s lights,” windows within the train carriages designed to allow observation of other compartments and installed by several companies such as the South Western Railway. These portholes were meant to reduce seclusion inside the coach, but were regarded as an intrusion—and raised fears about Peeping Toms. In other areas there were calls for increased communication on the trains such as cables to signal an emergency but problems of logistics prevented this.

The railways seemed to cause anxiety and concern about madness because of the noise and the unpredictable nature of the railways. There were also beliefs within the medical profession that the vibrations of the railway carriage could have a disastrous effect on people’s nerves. And it was impossible to predict who might be the one to be driven mad. As Professor Amy-Milne Smith wrote, “not only might you be attacked by a madman on a railway journey—you might become one.” As a result railways became associated with insanity. What might be thought of as more like post-traumatic stress disorder today was viewed as a form of nervous disturbance by Victorians.

Eventually, the outrage over mental-health problems on the railways and the “railway madmen” faded out as inexplicably as it had appeared. The blood-and-guts-loving Victorian media moved onto the next story, though onboard disturbances still happened from time to time. In 1894, one naked individual even launched a full-on assault on the train by disabling the communications and then attacking those onboard, roaming around at will through the train. The whole affair was treated as puzzling, but not frightening—the attacker was battled and jabbed back with the pointy end of an umbrella.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook