The Art of Repairing Broken Ceramics Creates a New Kind of Beauty

Pottery is fixed for practical purposes—and aesthetic ones as well.

Throughout time and across cultures, ceramics have been both functional and decorative. A few years ago, archaeologists discovered 20,000-year-old pottery fragments in a cave in southern China, evidence of an ancient, nomadic kitchen. Just last year, four canopic jars were found in a newly unearthed ancient Egyptian cemetery—there, and in many other such tombs, they held mummified organs. And in 19th-century America, porcelain dinnerware served as a not-so-subtle status symbol. Porcelain, a high-fired clay with a fine surface texture, was so delicate and valuable that it was often given as a diplomatic gift.

Ceramic vessels are useful and ubiquitous, but can also be fragile, so it is inevitable that they might chip, crack, or break. This damage can happen at any point in the life of a pot, vase, or krater: fresh from the kiln, on board a ship in transit, or after a tumble from a shelf. Fractured pottery has a long, globe-spanning history, too. In Rome, the sherds of seemingly countless amphorae form Monte Testaccio, a giant hill composed entirely of the remains of oil jars broken in transit. George Washington knew this problem well, too. In a 1758 letter to British merchant Thomas Knox, he claimed his “Crate of Stoneware dont contain a third of the Pieces I am chargd with, and only two things broke.” And during the World War II era, as Japanese-Americans faced the imminent risk of being taken away to concentration camps, some broke their prized, authentic Japanese porcelain heirlooms in protest.

Just as there are many ways to mend a broken heart, cultures around the world have used different approaches to repairing broken ceramics as well. The tradition of repairing these items goes back to antiquity. “We think of recycling as a modern-day practice, but really the mentality of throwing things away when they break is the more modern phenomenon,” says Angelika Kuettner, Associate Curator of Ceramics at Colonial Williamsburg, in an email. “History is filled with accounts of objects of many types (of value to the owners) being mended or repurposed.” But this practice wasn’t always for practical, utilitarian purposes. Pottery’s dual role as both objects of utility and markers of wealth has made repairing broken vessels doubly important. “There are quite a few period accounts of mended ceramics, perhaps no longer fit for use on the table, being used to dress a bowfat (china closet or cupboard),” Kuettner says. “In other words, although broken, they could continue to be used to show status as display pieces.”

Two curators and a conservator have helped us break down the ways busted up ceramics have been put back together—often to quite beautiful effect—for thousands of years.

Staples

The story goes that a prominent military ruler in 15th-century Japan had an even older Chinese celadon-glazed bowl that broke. It was so precious, and he loved it so much, that he sent it to China to be replaced. Unfortunately, such was its rarity that replacement was impossible, so the Chinese repaired it instead. It came back to the ruler with holes drilled through each side of every break, and metal staples put through those holes, thus holding the fragments together. This mechanical Chinese technique for mending pottery, also known as “rivet repair,” ultimately ended up spreading west to the rest of Asia via the Silk Road.

Sarah Barack, Head of Conservation and Senior Objects Conservator at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, categorizes ceramic repairs into two main approaches: external and internal. Staples were external, highly visible, as they did not lay flush with the rest of the surface. Because ceramics have often been on display, whether they were in use or not, this seemingly crude fix could have been considered an eyesore. But according to Barack, it depends on how the mended pottery was displayed. “The rivets that I’ve seen, for instance, are generally on the outside—the underside—of a plate. So those staples weren’t visible from the front side,” she says. “If you weren’t showing the object all around you wouldn’t really see [them] on the back side.”

Kintsugi

Up until about the 12th century, Japan imported ceramics from China, but it wasn’t until the 14th century that these objects became important in society. Louise Cort, Curator Emerita for Ceramics at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, says that this is when they started being linked to the custom of tea drinking among elite society. “In the 16th century tea drinking evolved into an aesthetic practice that focused on individual ceramics displayed and used in the tea room,” she says. “Kintsugi repairs appear to be closely associated with tea.”

Kintsugi, the art of mending breaks and losses in ceramics with lacquer and gold powder, developed sometime by the 17th century. Lacquer (known as urushi, and made from tree sap) has been used in Japan as an adhesive since antiquity, but the sprinkling of powdered gold onto the wet binding agent shows how this repair technique came to involve aesthetics as well as function. Simply put, gold is expensive, so a kintsugi-repaired vessel was a clear, yet subtle, symbol of wealth. Unlike rivet repairs, kintsugi both fixed broken ceramics, and beautified them into distinct works of art.

Due to the frequency with which tea bowls were dropped, kintsugi’s “golden seams” eventually became a fairly standard attribute of traditional Japanese tea ceramics. These repairs were performed by lacquer specialists, who generally trained in the technique for at least a decade. Because of this long road to becoming a master, Gen Saratani, a third-generation Japanese lacquer restorer who works and teaches kintsugi in New York, says there are few masters of the craft still working today.

Adhesives

Adhesives are a more internal style of repair than staples, and more subtle than kintsugi (which is itself an adhesive technique). They come in many forms—from putty to paint to “china pastes”—and interlock the micropores exposed by a break. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this method has always been more accessible for people to perform themselves, without having to outsource the work to a specialist.

“There are many 18th-century recipes (which were often referred to as ‘receipts’ in the period) for ‘china glues’ that individuals could make at home to repair their ceramics,” Kuettner says. In colonial America, these recipes were printed in housewifery journals and other publications. Hutchin’s Improved Almanac, published in New York, issued a recipe for “an Exceeding fine Cement to mend broken China or Glasses.” Alternatively, premade adhesives were available for sale. One man, Anthony Lamb, advertised his “Putty for mending China” in the Connecticut Journal in 1779.

For porcelain repair in particular, Barack says that a mixture of linseed oil and white lead paint was often used. “[It] replicates the fineness of the surface of porcelain and gives it sort of a polish,” she says. “And on the inside it might [have been] filled with plaster to sort of hold it all together.” Ancient ceramics, on the other hand, were likely patched up with naturally available substances. “Bitumen, a natural resin, was an ancient adhesive that was known,” Barack adds. Today, on the other hand, professional conservators use modern materials such as epoxies and reversible adhesives.

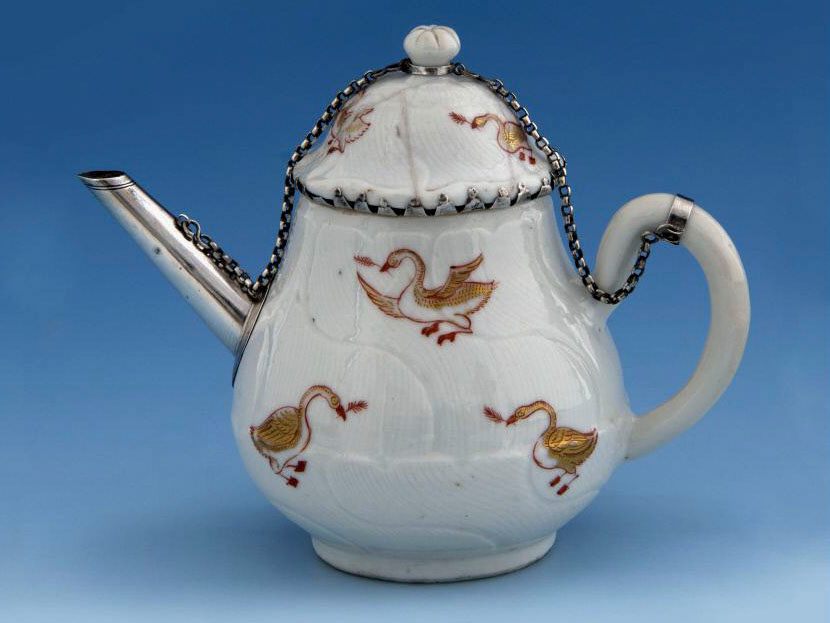

Mounts

In early prints and paintings depicting domestic American life, there are several instances of ceramics (teapots, especially) with spouts and handles that had been replaced with tin or silver. As an expert on the pottery of Colonial Williamsburg, Kuettner says that “many metalsmiths supplemented their businesses by also offering to repair ceramics.”

In her article, titled “Simply Riveting: Broken and Mended Ceramics,” she recounts one instance in which a certain James Rutherford of Charleston, South Carolina, advertised himself as a “regular-bred gold and silver smith … who … likewise works in jewelry, and clasps broken china in the neatest manner.” Silversmiths not only repaired broken ceramics, but added on to them as well. Thomas Shields, of Philadelphia, was known to add a chain from a teapot’s cover to its spout, likely to prevent further breakage when handling.

These shiny additions were often simply for aesthetic purposes. “Sometimes silver mounts weren’t [used] because something was damaged, but very often a piece of porcelain would be sent to Europe and then it would be fitted with a silver mount for the market,” Barack says. “And it wasn’t a repair, it was just an aesthetic decision to allow [the piece] to be part of a decorative arts scheme in a room.” Pottery owners concerned with how their vessels matched their decor treated ceramics from a decidedly privileged position—after all, there was wealth to be flaunted. Silversmiths and metalworkers were called in to perform this specialized decorative, repair, or replacement work to increase the value of a given item. “Silver is a very valuable metal,” Barack says. “So like kintsugi, you’re using a medium that’s valuable, that has specialized knowledge behind it, and has a crafts practice and tradition.”

The repair of damaged ceramics has a long history, patched together from pieces scattered all over the world. It is a form of historic conservation that is not only site-specific, but culturally specific, too. The tendency to want to fix an imperfection is a human one—and then there is the desire for survival, such as when fixing and reusing a pot, bowl, or plate, is the only option you have left. Regardless of how or why the repairs are done, their combination of beauty and function shouldn’t be allowed to slip through the cracks.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook