During the Great Depression, ‘Penny Restaurants’ Fed the Unemployed

Dishes cost a cent, or even came free.

New York’s 107 West 44th Street had been home to Bill Duffy’s Olde English Tavern. But with the Great Depression emptying wallets and Prohibition yet to be repealed, it was difficult for upscale establishments to stay open. In place of the old restaurant’s “merriment,” the New York Herald Tribune reported, a new restaurant was opening at the same address. It could accommodate crowds that would have swamped Duffy’s: 9,000 customers a day. The cuisine was humble: Pea soup and whole-wheat bread featured prominently on the menu. But it was dirt cheap, an aspect reflected by the establishments’s name. The Penny Restaurant was a place for the downtrodden and not-quite penniless to have a bite to eat.

The establishment was not without precedent. So-called “penny restaurants” were in operation in the late 19th century in cities across the United States. Though popular with teenagers hankering to eat on a shoestring, the restaurants were usually run as charitable projects. T.M. Finney, who managed a St. Louis penny restaurant run by the local Provident Association, laid out the enduring modus operandi of charitable restaurants. “The aim of the scheme is to afford poor people to maintain their self-respect and reduce the number of beggars,” Finney stated.

At his establishment, every item cost a penny: A meal of half a pound of bread, soup, potatoes, pork and beans, and coffee only cost hungry customers five cents. Breadlines, where miserable hundreds waited hours for free food, were an all-too-common sight during the Depression. Penny restaurants were the dignified alternative.

Penny restaurants always appeared during times of financial trouble, but they reached their greatest prominence during the Great Depression. In 1933, unemployment was at 25 percent nationwide. A whole new cuisine of make-do was developing across the country, from starchy slugburgers to pork masquerading as higher-end chicken. At penny restaurants, food was simple and often meatless.

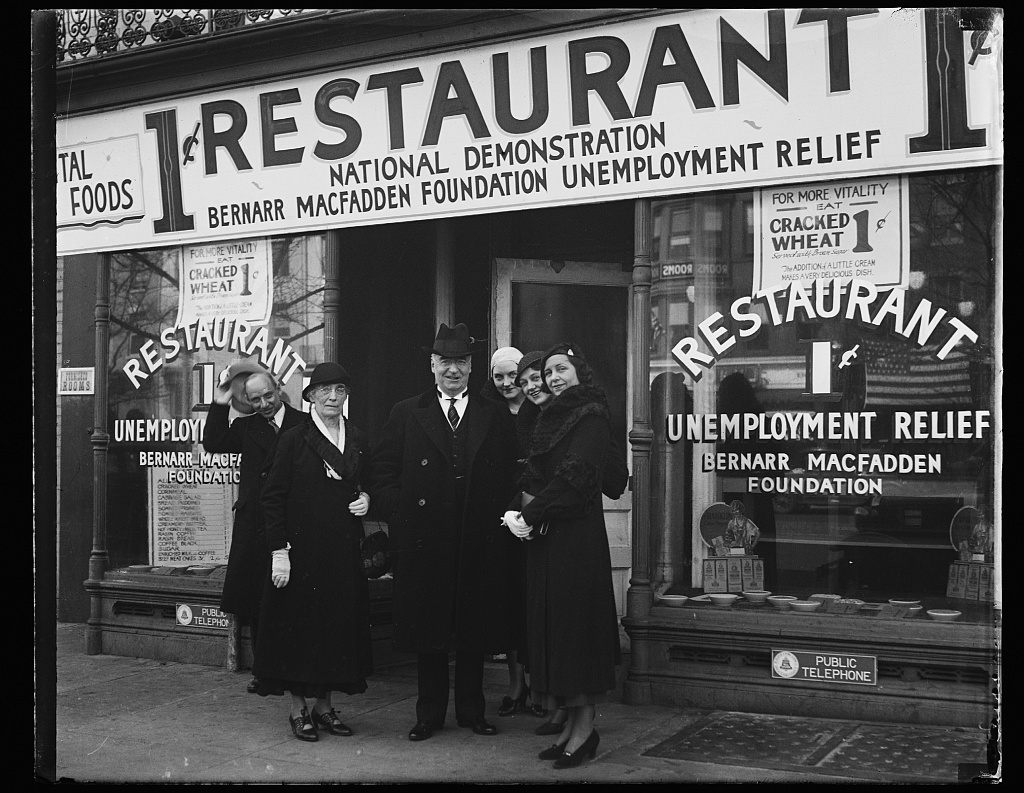

In New York, the best known penny restaurants were run by Bernarr (yes, Bernarr) MacFadden, an unlikely charitable pioneer. Most people knew MacFadden for his muscles. One of the founding fathers of American fitness culture, MacFadden lifted weights and was vegetarian. He’d run penny restaurants at the turn of the century.

His 1933 restaurant on West 44th Street had four stories, one for fine dining, two where customers could sit at shining white tables, and one floor for eaters to stand and eat simple food. MacFadden ran a massive publishing empire, and many of his magazines raised eyebrows for their radical diet ideas, out-there moralizing, and numerous photos of fit young people. But he also used the proceeds to open several more penny restaurants, where customers paid a pittance for prunes, soup, and healthful whole-wheat bread (MacFadden considered white flour poison). Even presidential daughter Anna Roosevelt dined at his establishment.

But the eccentric MacFadden was outdone by a Californian restaurateur. Most penny restaurants were ephemeral, lasting a few months or a few years. But one Depression-era eating establishment still exists and is still churning out jello: Clifton’s Cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles.

Started during the Depression, the Cafeteria was part of an 11-restaurant chain that spanned California. They were launched in 1931 by Clifford Clinton, the scion of a successful restaurant family. But the Clintons were also pious: Clifford and his parents spent years in China feeding the hungry with the Salvation Army. With this eponymous chain of cafeterias, named by combining his first and last names, Clinton hoped to attract the masses with his massive, wildly decorated eateries. But he and his wife, Nelda, also wanted to feed those who couldn’t pay. His eateries boasted the slogan “Dine free unless delighted.”

In the original restaurant’s first three months of business, ten thousand customers took him up on the offer. But the Clifton’s cafeterias were some of the largest in the world, and enough customers paid their bills to make them a success. The eat-free policy, Nelda later said, was meant to lend dignity to hungry people in precarious positions.

The same year that Clinton opened his first cafeteria on South Olive Street, the soon-to-be-named Clifton’s Pacific Seas, he also opened a penny cafeteria serving soup and bread. It made him unpopular with some locals, who believed Clinton was feeding the lazy and “undeserving.” (Clinton rebutted this with a printed pamphlet that asked why the deserving should also go hungry.) His most famous and still-existing cafeteria, in Brookdale, opened in 1935, under the same “Golden Rule” policy as the first. Four years later, it got a makeover with flowing streams, redwood trees, and grottoes.

With its rustic woodland surroundings, it became a popular dining spot for rich and poor alike. Later cafeterias around the state had their own themes: The Olive Street establishment gained a South Seas veneer, with a “Rain Hut” where guests could experience a tropical shower every 20 minutes. Later cafeterias featured decor riffing on Mediterranean design and Charles Dickens. While running his restaurants, Clinton kept busy. When he started a citizen campaign to investigate corruption in the city, his house was bombed and his cafeterias targeted. Suspecting that the graft went all the way to the top, Clinton waged a successful campaign to recall the mayor.

During the depths of the depression, penny restaurants were lauded for giving Americans the strength to keep searching for jobs. But by 1935, the economic clouds were lifting. Daniel W. Delano, the proprietor of one penny cafe in Washington D.C., told a reporter that the number of customers both paying and eating gratis had plummeted, and those that did come seeking meals were mostly children.

When the Depression ended and the post-war American economy boomed, many penny restaurants shut down. But Clifton’s fate was entirely different. The restaurants entered their glory days, and lines to enter the Brookdale location stretched down the block. That cafeteria remains open today: The Brookdale location was expensively renovated to much fanfare in 2015. Though customers can no longer dine free, it’s a relic of a time when a free restaurant meal was an alternative to a night in the breadline.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook