Resurrecting the Incredible Flower Crowns of Old Ukrainian Wedding Photos

Pinterest boards around the world, unite.

Back before the traditions of Eastern Europe were changed by war and Communism, as a young girl grew up in Ukraine, she would be allowed to decorate her hair, simply at first, with flowers, ribbons, and tendrils of green. In the summer, the flowers would be fresh; in the winter, they might be made of paper or cloth. Once the girl wanted to announce that she was ready for courtship, she would put on a much more elaborate headdress of flowers. When she found a man to marry, her friends would weave her a wedding wreath, which should be the most beautiful she would ever wear.“That was the last time a maiden could wear a wreath,” says Lubow Wolynetz, the curator of folk art at New York’s Ukrainian Museum. “Once she was married she could no longer decorate her hair or head.”

In the 20th century, this tradition disappeared; in Communist Ukraine, to wear traditional dress or embroidery became a symbol of protest. Pictures of these wreaths survived, though, and even some examples. But as Ukrainian independence and identity came under threat in recent years, there was a revival of this tradition.

It has become trendy to wear flower wreaths—they are “sold everywhere in Kiev,” a Vogue correspondent reports—and one studio, Third Roosters, is using old photos of traditional wreaths to recreate extraordinary headdresses.

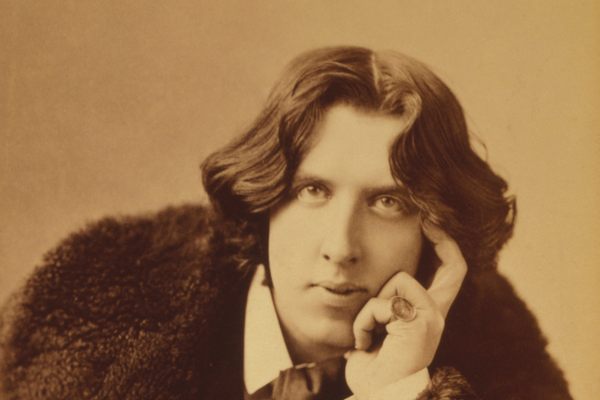

Third Rooster’s aim with this project, is recreate authentic Ukrainian looks, from the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, before World War I. The old photo above was taken in the early 20th century, and it pictures a couple at their wedding. The design of wedding wreaths differed across regions of Ukraine; this one is from Kornych village, in the region of the Carpathian mountains, in the west of the country. A wreath like this one would have been made in just one day, says Wolynetz, on a maiden’s eve. The bride’s friends would come to her home, where they would find everything they needed to prepare the wreath. They might work until dawn, but they would finish it.

Ukrainian weddings traditionally took place in the late fall, so although the wreaths look to be bursting with plant life, they might have been made with artificial flowers, made from shells, cloth or paper. Only one part had to be alive, according to Wolynetz—the winding stems and leaves of periwinkle, which never dies. It was a symbol of eternity and beauty, and it’d be included in every wreath.

These days, creating one of the wreaths takes much more than one day. “The process of creating each image with a wreath is very long and laborious,” Third Roosters wrote, in response to questions from Atlas Obscura. Each one is modeled after wreaths that have been preserved in museums or photographs, which the studio studies to understand how the wreaths are made and from what materials. They’ve learned to make wreaths from wax, paper, and flowers—to make a large one, weaving the frame and flowers, by hand, out of paper, takes a month. Third Roosters started recreating these wreaths in 2015, as part of a project to support those resisting Russian influence in eastern Ukraine. They dressed the wives, sisters, and mothers of fighters at the time in outfits inspired by the traditional clothes of Ukraine; the wreaths were some of the most striking pieces.

“People want to go back and delve into the past, they want to bring out the beautiful parts, the aesthetic parts into their lives,” says Wolynetz. “In Ukraine, probably because we regained our independence after so many years of being occupied, there is more of a tendency to delve back into the past and your heritage. The occupying forces didn’t always allow you to perform these old traditions.”

For many years, clothes like these were “symbolically linked to national identity and unity,” one researcher told the New York Times in 1994, and in the Soviet era, wearing them was a way to protest the powers that tried to erase Ukrainian distinctiveness. Now, as the country continues to push back against Russian influence and intervention—the conflict between Ukraine and Russia has not gone away, despite an official ceasefire—these wreaths are doing the same symbolic work.

* Update: This story was updated on September 17, 2019, to reflect the current political situation in Ukraine.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook