The Myth of the Damsel on the Railroad Tracks

Tying up women in front of oncoming trains was never a real thing.

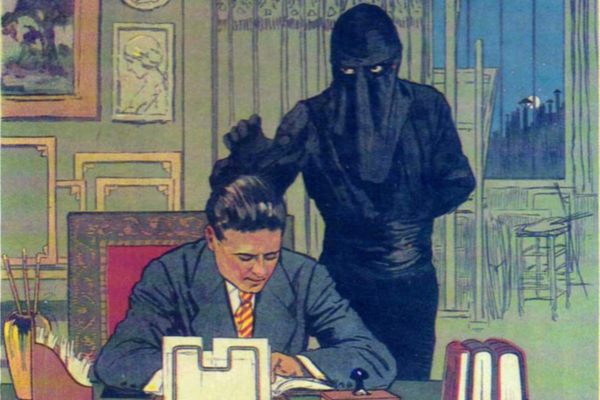

Most people are familiar with that most clichéd of old cinema tropes: the damsel-in-distress, tied to the railroad tracks by a dastardly villain, only to be saved at the last moment by the dashing hero.

As a method of murder, this seems so melodramatic and old-timey that it must have originated back in the days of the silent film. But that scene rarely ever occurred, and probably not in the way you think it did.

“It’s really a tricky subject because people have this incredibly specific trope in mind (villain in top hat and mustache, screaming female victim, said villain tying or chaining said victim to tracks),” says Fritzi Kramer, creator of the silent film blog, Movies Silently. “But then when they are told that it was not actually common in silent film, they quickly grab for something, anything to prove that it happened.”

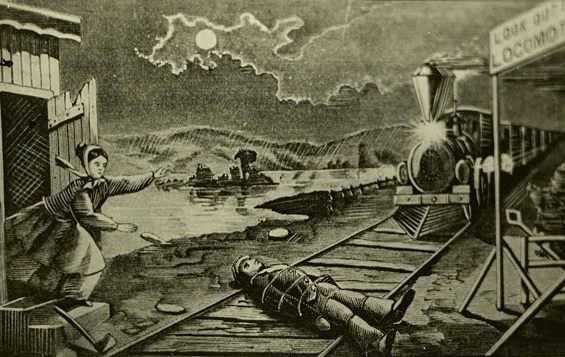

On her site Kramer identifies the first occurrence of this type of scene in an 1867 Victorian stage melodrama called Under The Gaslight. The play’s stage directions call for one of the characters (named Snorkey) to be tied to the train tracks by the villain. It’s close to the scene we’re familiar with save for the fact that the person on the tracks is a man, and he’s saved by the leading lady.

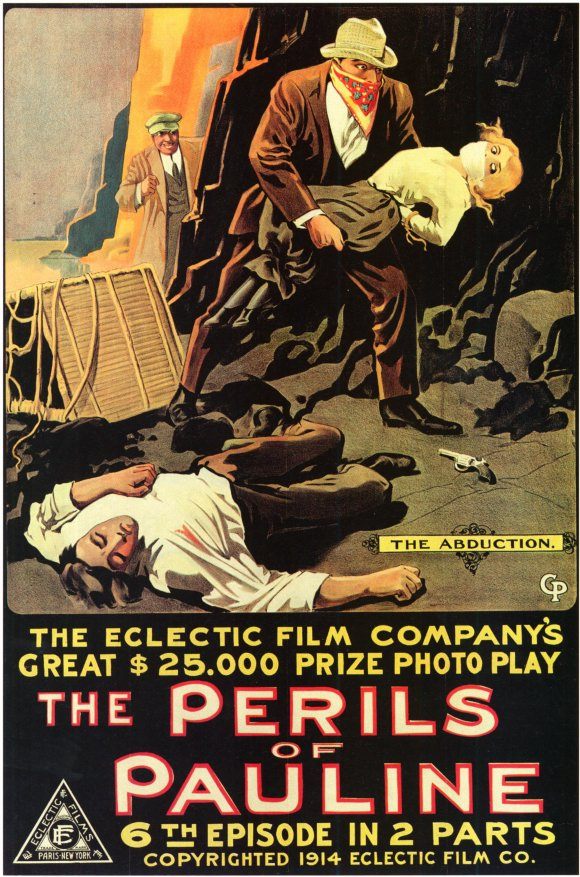

This sort of train-based peril became a regular element of the melodramas as a cheap and easy way to create suspense. Moving into the early-20th century, and the silent film era, many films took their cues from those same 19th-century stage dramas. One of the more famous examples of this type of story was the serial The Perils of Pauline, which saw the titular heroine encounter all kinds of scoundrels and villains each week, who would put her in life-threatening danger—although it is important to note that she was never tied to the railroad tracks. This sort of overblown adventure tale became a well-known story type in its time, but that melodramatic style also inspired some comedies, which spoofed some of the more overused elements of the genre.

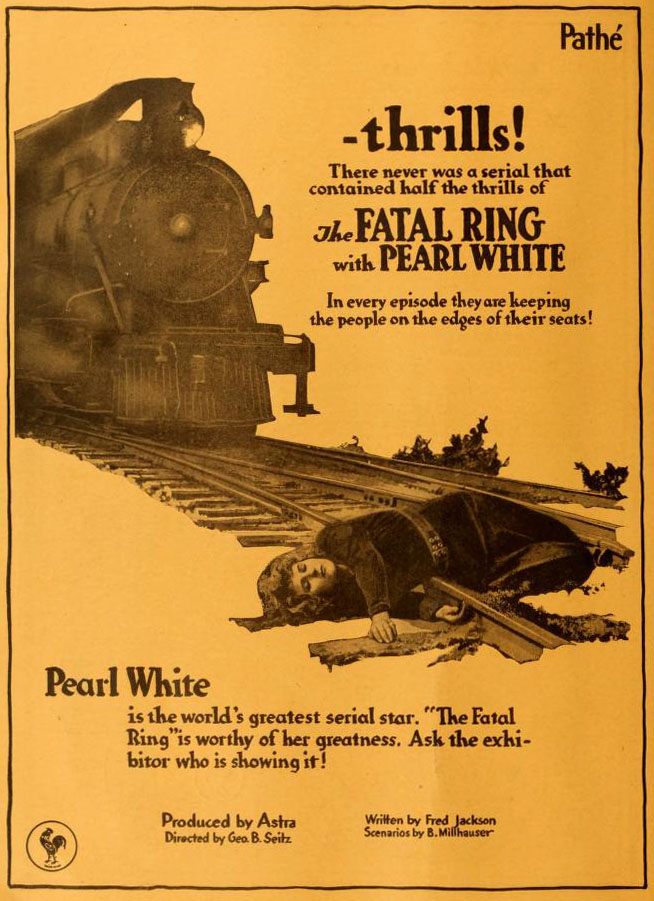

At the time, trains were a major form of transportation, and consequently showed up as set pieces in many silent films. There were often instances wherein a character would end up on the train tracks, either from falling or being knocked out, such as in the movie, The Fatal Ring. In many cases, like with that first instance, it would be the male hero who would end up on the tracks, having to be saved by the woman.

Many of the elements of the trope most people are familiar with are there, but the mustachioed villain cackling while they tied a helpless woman to the tracks was just not something that happened in dramatic silent films. Not that that has stopped people from assuming that it did.

“This is an incredibly specific trope but people trying to prove it was a common event in silent films will use comedies and any railroad peril to try to prove their point,” says Kramer. As trains were the form of public transit during the silent era, it’s hardly surprising they were included in the action. But since the trope has such specific ingredients, I think it is reasonable to demand that all those ingredients be present.”

The specific scene as we know it didn’t come into its own until after the heyday of the melodrama, once the genre became less popular and people started to spoof the overblown stories. Some of the most oft-cited examples of the woman-tied-to-the-tracks trope are from a pair of silent comedies Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life and Teddy at the Throttle. Both of these films were send-ups of the cartoonish lack of subtlety presented in melodramas, and featured scenes in which damsels were tied (or chained) to the tracks.

It is comedies like this that most often get referenced when people look into the history of damsels on the tracks. “This is like taking the Saturday Night Fever spoof scene from Madagascar and using it to ‘prove’ that disco was the number-one music of the 2000s,” says Kramer.

Despite being a sort of half-remembered tribute to a scene that had never actually existed, the damsel on the tracks quickly became the kind of recurring trope that everyone is familiar with, even if they’re not sure where they first saw it. When The Perils of Pauline was remade with sound in 1947, sure enough, Pauline ended up tied to the tracks.

Tying women to the train tracks pretty much became the signature move of the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoon character Snidely Whiplash, a caricature of a scheming melodrama villain. And in the modern day, the scene has morphed into a kind of visual shorthand for cartoonish villainy, even if it isn’t found in nearly as many films and TV shows as it once was.

Kramer attributes the continued connection of the trope to the history of silent film to a number of factors, including the gulf of time that exists between the era of the silent film and the modern age, and the relative accessibility of silent comedies that featured the trope as opposed to the dramas they were inspired by. The much more prominent peril in silent films was the threat of sexual assault—having someone tied to the tracks was a much less offensive threat in later representations and homages to the old silent films.

Correct or not, the image of the damsel on the tracks seems like it’s here to stay, and in Kramer’s experience people don’t want to know the truth. “A pretty decent chunk of the population is convinced that screaming damsels were constantly lashed to tracks by mustachioed villains,” she says. “The fact that this trope was incredibly rare even in serials does not dissuade them.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook