How Two Men Tried to Start a Hate-Free ‘Gay Town’ in the Nevada Desert

Stonewall Park was a mid-1980s dream that never quite came to fruition.

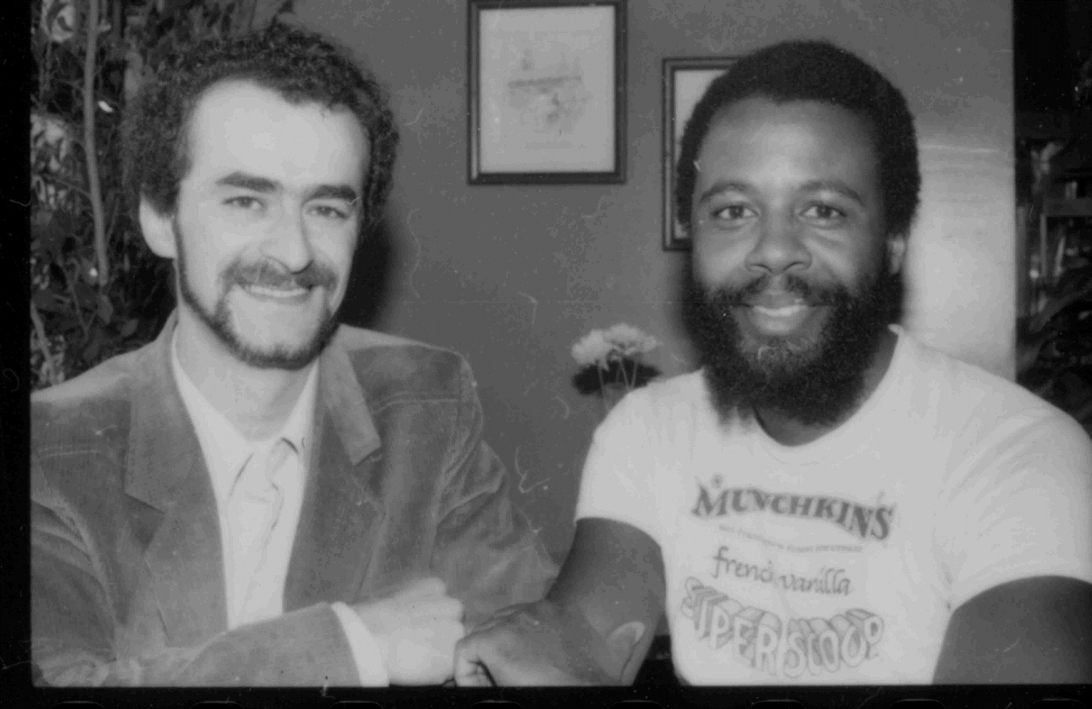

Fred Schoonmaker was the visionary; Alfred Parkinson, whom he called his husband, his most devoted disciple. The two men lived in Nevada in the mid-1980s, at the height of the AIDS crisis, when legally sanctioned homophobia (there was a federal, enforced law against sodomy) combined with HIV-inspired hysteria. Many believed gay men represented not just a risk of moral contagion, but literal infection: morticians regularly refused service to the grieving families of HIV-positive men. Being gay was hard; being black and gay, as Parkinson was, still harder.

But Schoonmaker had a solution as drastic as he felt the climate merited. The two men would found a community exclusively for LGBTQ people, where they could walk freely hand-in-hand down its streets. Stonewall Park, named for the 1969 riots in New York, would be a literal gay village in the middle of the Nevada desert. It was for them as a couple as much as it was for their community, he told friends, but it was also his legacy to the younger Parkinson, whom he expected to outlive him—a “safe and peaceful place” away from the hatred of the rest of the world.

Schoonmaker had grown up far from Nevada, in Wellsburg, West Virginia. It was a river town with a steel plant, and a diminishing population with historically high Ku Klux Klan membership. At five, Schoonmaker realized he was “definitely different;” by 14, he was scrabbling change together for a $1.25 60-mile bus trip to Pittsburgh, home of the nearest gay bar. Somebody there would always pay his way back, he told the Washington Post in 1986. “I don’t know where my parents thought I was going.”

Being a gay teenager in the shadows of the West Virginian hills could be brutal. Though Schoonmaker found refuge at the end of the bus route, two of his close friends were unable to accept being gay, and killed themselves at the age of 16. These experiences, suggests historian Dennis McBride in his book Out of the Neon Closet: Queer Community in the Silver State, planted the seeds for Schoonmaker’s belief that gay people could only be happy in a segregated society, as did time in same-sex communal living situations in San Francisco in the 1960s. “You get tired of all the daily jokes, the humiliation. If you’re not gay or lesbian, there’s no way to put yourself in that position. I was never beat up or anything. But you don’t have to be the victim of a fag-bashing every six weeks,” he told the Post.

Parkinson’s origins are less clear. He was from the Bay Area, and quieter than Schoonmaker: one journalist described him as “an oddly elusive man whom one always seems to see just disappearing around the edge of a building.” McBride recalls someone who had “internalized a lot of the horror and animosity that surrounded the gay community in those days”—less expressive or outgoing than his partner, despite being “very emotional,” he says.

They met in the early 1960s and moved to Reno, Nevada, where Schoonmaker had eventually drifted into casino work. Conversations between the men about a shared dream for a normal, socially accepted relationship, evolved into wondering how to make such a dream a reality—creating a place where gay people could not just be out, but utterly humdrum. “You’re not making any statement, not providing an educational experience that everyone can participate in.”

A small and dedicated group of local supporters began to form around the project: among them a retired librarian; a trans newspaper columnist; a prominent city attorney. Though not all felt as strong a pull to segregated life, many were captivated by Schoonmaker’s dream. “[He] was so charismatic that you couldn’t help but join him,” supporter Marguerita “Stormy” Caldwell told McBride. “With Fred’s enthusiasm, nothing was impossible. I was willing to work with him all the way.” From their base in Reno, they started a gay magazine, the Stonewall Voice, to disseminate information and advertisements for the community, and incorporated the Stonewall Park Association in February 1984.

In the spring of 1986, Schoonmaker and his team began to solicit donations. They left collection jars in gay bars across the state, hoping to accumulate enough coins and bills to get the project off the ground. Gay and lesbian groups around the country received mailings about this proposed segregated resort community. Schoonmaker envisaged “a casino, tennis courts, spas, condominiums and single-family homes,” and a place for over 24 million LGBT Americans—by his calculations—to live without prejudice.

“STONEWALL is telling the world we exist! That we have feelings!” Schoonmaker wrote, in one press release. “That we deserve equality! STONEWALL PARK is our living symbol to the world that we will no longer live in fear!” Nationally, it failed to attract the attention of mainstream LGBT organizations, who viewed it with considerable skepticism if at all; locally, however, the idea began to gain some traction.

As Schoonmaker began to look for a site, even people entirely unconnected to the group began to hear about their plans. Throughout Washoe County, local news outlets started to ask questions about this proposed community, and where it might be located; residents began to buzz angrily about how, and if, they might be affected. Janine Hansen, a member of the anti-gay Pro-Family Christian Coalition in Reno, said, “I can’t believe that under these circumstances with regard to AIDS that someone is trying to bring this into our community. … I’m not just concerned about AIDS, but bringing the homosexual ‘death style’ to Reno would be a blight on our community.”

In fact, the location they eventually landed upon was far from Reno, and out of Washoe County altogether. Silver Springs, Nevada, is out in Lyon County. It’s desert—golden grasses and crumbling piles of terracotta bricks—with about nine inches of rain a year. (The national average is 36.) Here, by this depressed and desolate town, a retired builder was selling 116 acres of sage scrub: Schoonmaker’s money was as good as anyone’s. But the surrounding community was quick to fight what they saw as an assault on their morals, straight out of Reno.

One woman claimed the new town would be a “singles’ market” resort, rather than the “small, quiet, rural, clean, healthy community” she wanted to live in. More than that, they feared a kind of cultural colonialism: that gay people “would take over the area,” she said.

Lyon County Planning Commission meetings grew toxic and tense. The project managers who had offered to help the team, a straight couple called Robert and Margaret Askew, suggested an alternative: Schoonmaker should start over, taking out the word “gay” from his marketing material, and with a more ambitious plan for fundraising. “Schoonmaker took the Askews’ suggestion as more of the homophobia and bigotry Stonewall Park was meant to mitigate,” writes McBride. In the resulting lawsuit, people who had been carried by the camaraderie of the team, and the power of Schoonmaker’s vision, began to lose faith. Some fell away from the group. The Silver Springs dream was over and Schoonmaker and Parkinson were all but chased out of town.

But despite these setbacks, Schoonmaker was undaunted. Next, he set his sights on Rhyolite, Nye County, a still more remote Nevada location on the edge of Death Valley. Named for a kind of granite, this famous ghost town exploded into being in an early 20th-century gold rush, housing thousands of glint-eyed optimists, as well as the people who sought to make a living housing and feeding them. Between 1906 and 1920, its population had rocketed from zero to nearly 12,000, and then all the way back down again. Very quickly, it had newspapers, railway lines, sex workers, promises—and then nothing.

Now, it was ruin-pocked and unpeopled, making the town ripe for the taking from rattlesnakes and jackrabbits. It was a tourist destination of sorts, with a house made entirely out of bottles and a baffling and wonderful selection of outside art, including a life-sized fiberglass ghost standing next to its bicycle. More than that, it had an important advantage, writes McBride: “As an incorporated city, Rhyolite could be operated autonomously of state or county law; in theory, Rhyolite could write its own laws and ordinances decriminalizing homosexuality.”

In mid-October 1986, the corporation signed a purchase contract with the town’s owners. All up, the bill was a cool $2.25 million, with the first installment due from Schoonmaker in mid-December. They expected a few dozen “pioneer” residents in the first few months, Schoonmaker told the press, with more to come once closeted people throughout the country began to pour into their new, permanent home.

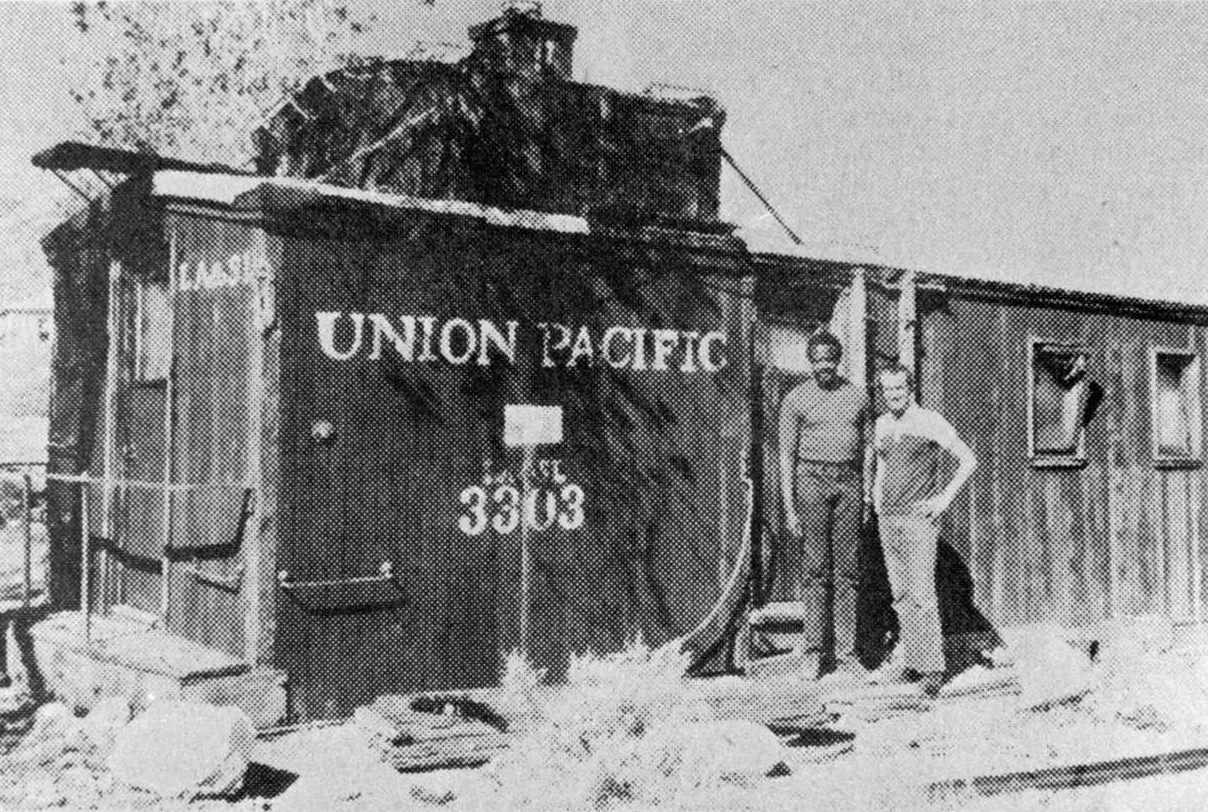

These pioneers would be housed in 225-square-foot cabins—everyone from busboys to neurosurgeons, he promised, taking a gamble on their promised land. Already, he and Parkinson had moved into a red railway caboose in the town with their four rangy dogs. Admittedly, there would be no jobs, at least at first, but contributions from residents and supporters would help fund their living expenses until the town could get on its feet.

Beneath an empty blue sky, Rhyolite’s scrub and ruins made it feel almost like another world, where the kind of refuge Schoonmaker envisaged might be a reality. Instead, it is just six miles from Beatty, a thoroughly terrestrial blue-collar hamlet of about 1,000 people on the edge of an atomic test site. It was the kind of place where you voted for your mayor by depositing a quarter in a jam jar; a place where, as Rye County Commissioner Bob Revert told the Post, “We accept atomic waste. We don’t accept the gay community.”

Today, Rob Schlegel is a realtor in Las Vegas. At the time, he was a friend of Parkinson and Schoonmaker and published the city’s LGBTQ newspaper, the Las Vegas Bugle. He remembers being part of a convoy of cars that came out to Rhyolite a dedication ceremony; how a Catholic priest who was a friend of the community used saltines for the ceremony. It seemed to have gone well enough, he says—until the only restaurant in town refused to serve them on the way back out, “because they didn’t want gays there. And I thought, ‘Hm. I’ve eaten here lots of times.’”

When the story broke in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, the townspeople were furious. Schoolchildren in Beatty nicknamed Rhyolite the highly ingenious “Fagolite,” while their principal fretted publicly that it would become “a breeding ground for AIDS.” As the town caught the attention of the world’s media—international camera crews, the New York Times, pun-heavy headlines about fairy tales, pansy patches, and closet communities—the people of Beatty fumed. Youth threw rocks, bullets, and slurs at the caboose and its inhabitants, while others scrawled “Save Our Children from AIDS” in red aerosol. Even the highway marker for the turn to Rhyolite was completely obliterated with black spray paint. They’d simply picked the wrong place, Revert explained. This wasn’t San Francisco, but “redneck country,” a place where they weren’t “gays”, or even people, but simply “queers.” Whatever they were, they weren’t welcome.

Schlegel also doubted that the project would ever work—even if the men did manage to amass the funds. “They didn’t realize that people didn’t want to separate themselves from mainstream society,” he says—from gay bars and bookshops, community centers and infrastructure. “Which is why I think their whole idea, although noble, was bound to fail.” But Schoonmaker believed that such structures could be built, and were will within the remit of the dream. ″After awhile people will realize that gays and lesbians paint their house, plant flowers and take out the garbage like everyone else,″ Schoonmaker told the Associated Press. ″This community will simply open a few more closet doors.″

Hordes of tourists started to arrive to rubberneck at the homosexuals and their ghost town. With them were a scattering of pilgrims, who would be slung overnight on a sofa in the caboose. One 24-year-old from California, Tony Pflaum, told the Post how he had walked the six miles from Beatty with “about 100 pounds of luggage”—all he needed to set his roots for “you know, probably the rest of my life.” Between the litter and the sagebrush, perhaps Rhyolite wasn’t much to look at, but the promise of walking down the street “without having a brick hit me upside the head” was a deeply compelling one, as was a dream of owning his very tobacco shop “with a carved Indian out front.”

Schoonmaker had always had plenty of dreams, but not quite as many dollars. McBride remembers him as an altruist, utterly dedicated to his fabulous ideas, but without “the means or resources to make it happen,” he says. “It’s people like Fred that might anticipate something wonderful, but they need other people to make it happen for them.” Many of those people had fallen away at Silver Springs. And so, when the first installment of the $2.25 million was due to from Rhyolite’s owners in December 1986, Schoonmaker and Parkinson were unable to pay it. They had raised just $6,000 from supporters—not even enough to make a dent in their costs. Opprobrium from their Beattian neighbors, meanwhile, was continuing to mount. Schoonmaker and Parkinson drove back to Reno in their pick-up truck, their hopes in tatters, through “a bunch of rednecks,” one friend told McBride. “And he came home and he called me and asked me if I could come over and so I did. And he just fell into my arms weeping.”

Even now, Schoonmaker was undeterred. That same friend, Caldwell, had previously offered him a 40-acre abandoned goat ranch in Pershing County. It was still more desolate, in the shadow of Thunder Mountain, with a community even more conservative than those of Rhyolite and Silver Strings. Caldwell tried to talk her friend out of taking the property, but he refused to listen, giving her a down payment for the land. A public campaign appealing to the gay community of Nevada mostly fell on deaf ears, perhaps due to these two failed attempts and the utter inhospitality of the new site. Predictably, opposition from county residents and their local officials was swift, and loud. Republican Assemblyman John Marvel from Battle Mountain compared the founders to his cattle. “Since I raise animals, I’m very gender-conscious. If I have a bull that doesn’t know the difference between genders, he goes down the road.” They were threatened with a shotgun by an immediate neighbor, while more than 200 people signed a petition against Stonewall Park.

Throughout it all, Schoonmaker was getting sicker and sicker. It’s not clear whether he knew that he was ill, but in March 1987, he was officially diagnosed with AIDS. The two men, who were often known as Fred and Fred, returned to Reno, where they lived in a dingy apartment on Carlin Street, just a few blocks from the highway. Even in the depths of his illness, Schoonmaker continued to plan, announcing a fundraising Gay Summer Camp in Thunder Mountain for that forthcoming summer. “We are assured the sodomy law will be enforced,” he warned in a letter to supporters. “You must be aware that your presence in Nevada could lead to harassment and/or arrest. This will come in legal form during the day and there is every possibility of danger at night.”

But the summer camp never happened. Schoonmaker’s condition worsened, until he was first bedridden and then comatose. The couple’s few remaining friends continued to visit, bringing them food and support. Nine weeks after his diagnosis, on May 20, 1987, Schoonmaker died of an AIDS-related heart attack at the age of 44. “When Fred died,” McBride remembers, “it was a tremendous blow to Alfred. Many of us wondered if he was maybe going to commit suicide over it.” He didn’t, but instead returned to the Bay Area with his husband’s ashes, leaving Nevada behind for good.

A seemingly impossible pursuit had proven as fruitless as many had feared, and the dream was entirely burned out. But while some friends lamented what Schoonmaker had put himself through in the last years of his life, others applauded his unwavering commitment to the dream. “The idea of Stonewall should live on in all of us,” Caldwell told McBride. “Maybe it was a lost cause, but it was a good dream.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook