The Treasures Blooming in Canada’s Largest Seed Catalog Archive

They were once considered disposable, but the Royal Botanical Gardens is putting 30,000 horticultural periodicals to good use.

The Royal Botanical Gardens—an 87-year-old, 2,422-acre swath of historic parks and gardens headquartered in Burlington, Ontario—is home to wonders animal, vegetable, and mineral. There’s a turtle tank in the main building’s lobby, native fish in the wetlands, and wild ducks and bald eagles flying over patches of protected land. Plants, of course, are everywhere, from rock gardens to nature trails to a two-story indoor greenwall. When I visited in early November, workers were building a miniature train set that snakes around an entire atrium, through scale models of Niagara Falls and the CN Tower.

There’s a special pocket of these wonders in an unlikely spot: a short tunnel that runs underneath a busy road, and connects one side of RBG’s main campus to the other. The tunnel’s walls boast a cornucopia of hand-drawn flowers, fruits, and veggies, blown up to massive proportions and tended by an array of characters.

Four members of the Queen’s Guard march atop a giant tomato. A portly man gives a thumbs-up to a sweet pea blossom as large as his entire torso. A young girl counts posies with a rake tucked under her arm, a cauliflower looming to her left like a big white planet.

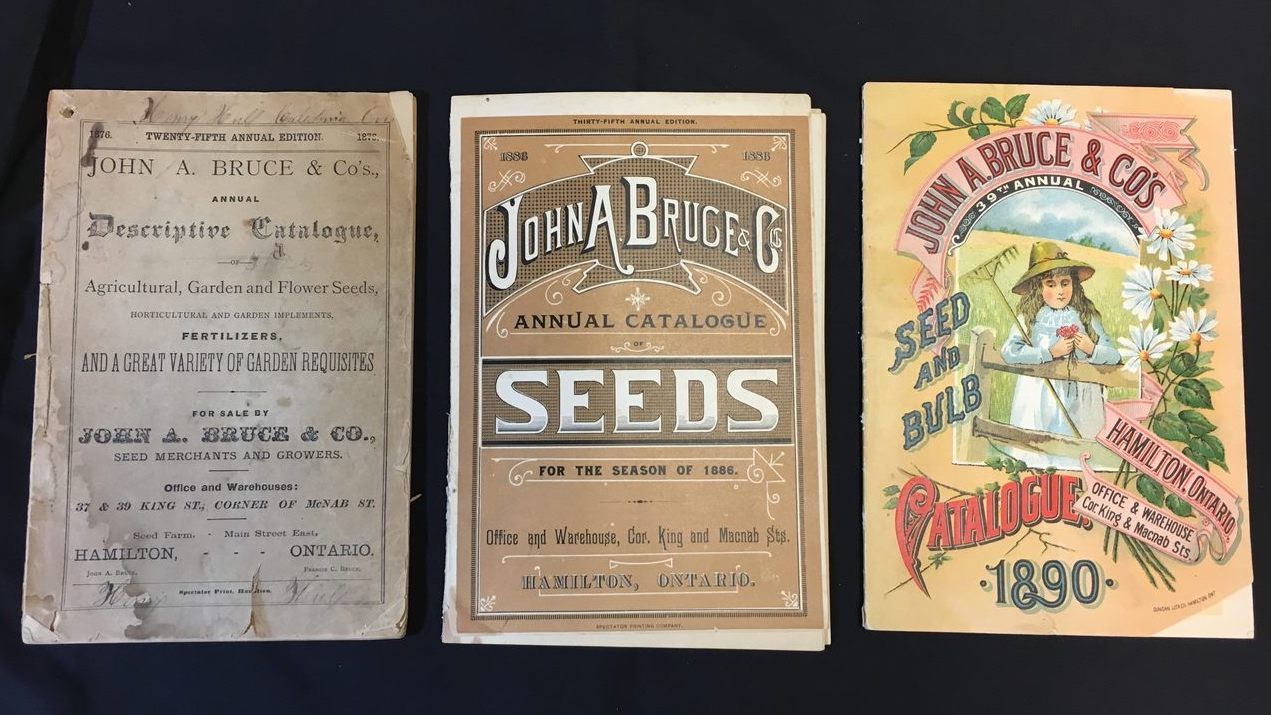

These drawings, most of which date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were originally created for an entirely practical purpose: to illustrate the horticultural catalogs that sold seeds, bulbs, and other products to gardeners and farmers in Ontario. Local companies such as John A. Bruce & Co—as well as international ones, including R.H. Shumway’s of Illinois—peddled their wares in this way, advertising everything from artichokes to zinnias.

These catalogs were meant to last exactly until the next issue came out, and no longer. (As the RBG’s head of science, David Galbraith, puts it, “You used them for toilet paper out in the one-holer the next month, because you didn’t need them anymore.”) But far back in the RBG’s main building, in a side room off of a quiet library, tens of thousands of historical seed catalogs have survived. Tended to by a squadron of dedicated curators, researchers, and volunteers, each awaits its moment in the sun.

Any plant-focused institution where people get their hands dirty ends up amassing seed catalogs, explains Erin Aults, the RBG’s knowledge resources management specialist, and the person currently in charge of the archive. In 1969, a forward-thinking librarian named Ina Vrugtman decided to keep the current stash, setting the stage for what was to come.

Heavy-duty collecting began ten years later, with the formation of the Centre for Canadian Historical Horticultural Studies. After a few large donations got things going, the RBG began sending out calls to the public through local newspapers and journals, and via the CBC. They scoured book dealer listings, and reached out to collectors they thought might be sitting on a treasure trove. People were happy to oblige: “Items came from a mix of nurseries, societies and other organizations, and individuals,” says Aults.

Fast forward to 2017, and the RBG is now home to about 30,000 horticultural catalogs, the largest such collection in Canada. The archive stretches back to 1853 and continues up through the present day. Just under 10,000 of these are from Canadian companies; the rest, though international, have some bearing on Northern horticulture.

As Aults lays out a selection on the library table, similarities and differences quickly grow apparent. Some catalogs are printed in brown and white, or blue and black. Others boast the color palette of a 1960s comic book. All are stuffed full of ads for peas named “American Wonder,” “McLean’s Advancer,” and “Bruce’s Conquerer.”

It’s easy to get lost in any individual catalog, marveling at the varietal names—does this potato really look like a “Snowflake”?—or comparison-shopping for turnips. But researchers seeking information about a specific plant, place, or time period usually can’t afford to do this 30,000 times. As such, the archive’s secret weapon is a group of about a dozen volunteers who, every Tuesday and Thursday, come in to catalog the catalogs. “For the last decade, they have been putting in thousands of hours, sorting this collection out,” says Aults.

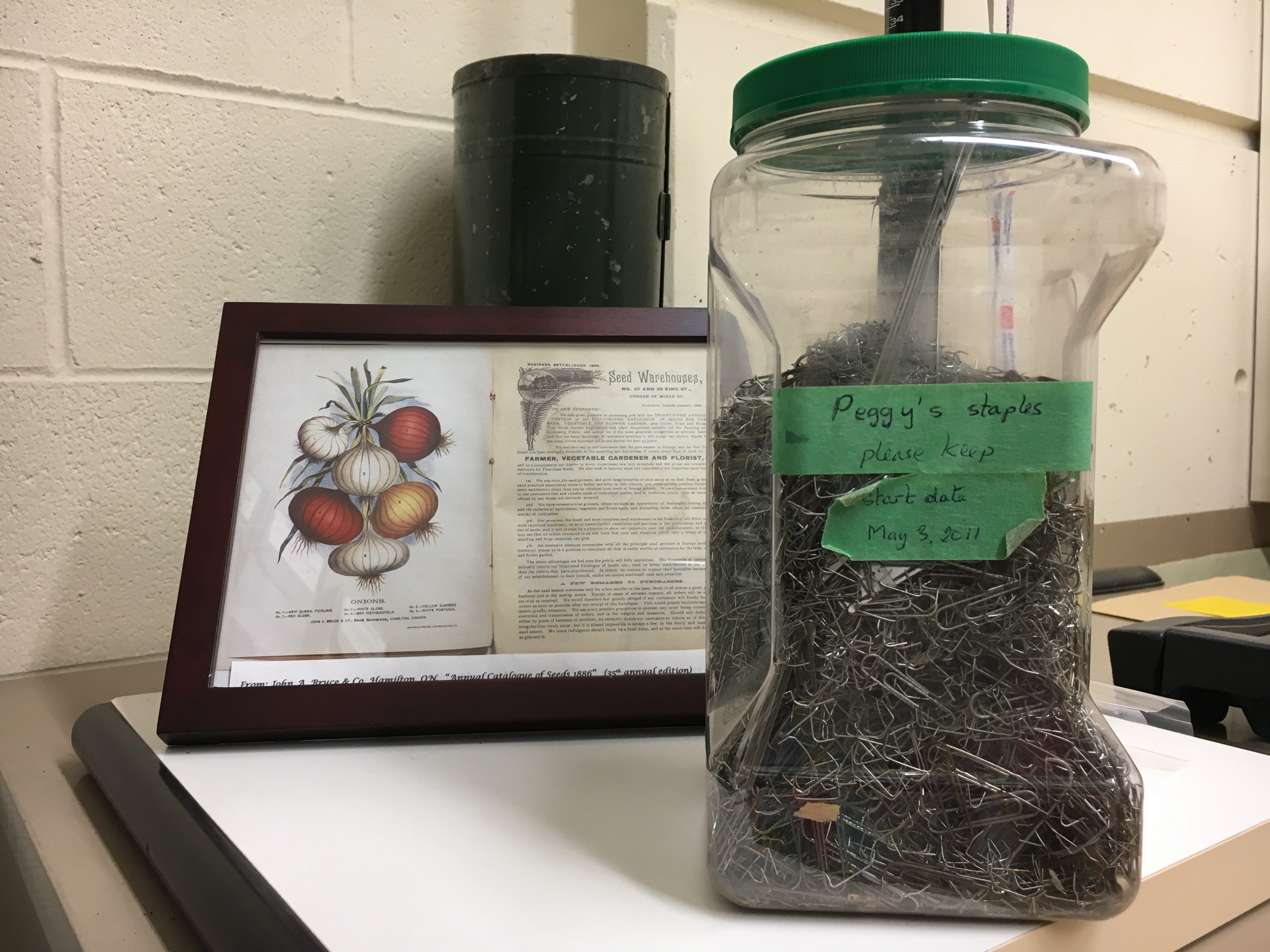

The volunteers have the process down to a science: “Henry Ford would love us,” says Maureen Baker, who has been doing data entry for the team for about five years. “You start at the basics,” Baker explains. “The very first thing is taking staples out. You cannot imagine how dreary that is.” (A clear canister, filled with about three years’ worth of spiky take, now sits proudly atop a file cabinet in the archival room.) After that comes sorting, alphabetizing, and ordering by year.

Someone uses special archival materials to clean off dark spots and stains. Someone else folds acid-free paper into envelopes that are exactly the right size for their contents. (“We have quite a few definitions and procedures on how to make a perfect envelope,” says Baker.) Titles, dates, and nursery names and locations are written on the envelopes. “They bring it to me, and I put the data in the computer,” says Baker. “Then we file it, and do it all over again.”

Once they’ve been properly organized, the catalogs can once again be put to use. So far, RBG employees and outside researchers alike have found a number of reasons to dig in. A couple of years ago, a doctoral researcher from the nearby University of Guelph used the catalogs to discover that soy was being grown and sold in Ontario a full decade earlier than people previously knew. “She rewrote the story of soybeans in Canada,” says Galbraith.

More recently, a landscaper from a nearby historical site pored over the RBG’s catalogs in order to plant a period-accurate kitchen garden. And when curators at a Toronto museum found a piece of paper with the name of a nursery and a bunch of random-looking digits, they called up the archives. “We had that seed catalog, and we found the numbers,” says Aults. “So then they knew what the people living in the house had ordered.”

Practiced readers can unearth less obvious details. “You can do a lot of sire-and-dame tracing” based on the positions of different plants in the catalogs, says Aults. “Or you can see, say, when lilacs became more hardy to Canada.” Flip through a few decades’ worth of nursery wares, and you can watch as the popularity of a single species waxes and wanes, and varietals appear and disappear. “[Companies] would keep trying to develop the perfect tomato, the perfect pepper, the perfect lettuce,” says Baker. Sometimes, contemporary villains pop up in the guise of heroes: “We can greatly recommend this grand vine,” reads an advertisement for “The Famous Chinese Kudzu.” Today, kudzu is considered a highly invasive plant.

Human journeys are hidden in there, too. One Missassauga nursery, Rowancroft Gardens, was founded by a lilac aficionado named Mary Eliza Blacklock in 1914, before women were common in the professional plant world. Having a complete collection of her catalogs helps to solidify her place in history. “I think that some of [the collection] also tells the stories of immigrants,” Aults says. “What plants they were bringing over, and what plants they missed from home that they wished were here. Some of the collections we have in here are from the Netherlands, or England. People brought them over so they could still order their favorites.”

The archive is still growing. Recently, the RBG acquired a massive new donation—20 boxes of more modern catalogs—from Niagara Parks. “We’ve got enough for about 3 or 4 more years of work, I’m sure,” says Baker. After that, there will surely be more, as the group continues to solicit new additions.

In Aults’ opinion, there is still a lot more digging to do, too. She hopes to digitize some of the collections in order to encourage people to take advantage of them. “We think there is more research use for these materials,” she says. “So far, the most visible use has been as art objects.” Color copies of some of the more striking covers decorate the walls of the research library, and of the RBG’s cafe. And then there is the tunnel, which—besides revitalizing a well-trafficked bit of infrastructure—manages to be a microcosm of the collection’s own journey: useful, beautiful, and still waiting underground.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook