The Time a Russian Empress Built an Ice Palace and Forced Her Jester To Get Married In It

Cruel joke, power move, or both?

It was 1740 and one of the coldest winters St. Petersburg, Russia, had ever seen. But few residents mentioned the bitter winter in letters or accounts. They were, understandably, distracted. While the rest of Europe shivered through the deep freeze, Russians were busy—building a palace. On the orders of Empress Anna Ioannovna, numerous craftsmen were charged with constructing an elaborate, fairy tale–esque castle, one made entirely of ice.

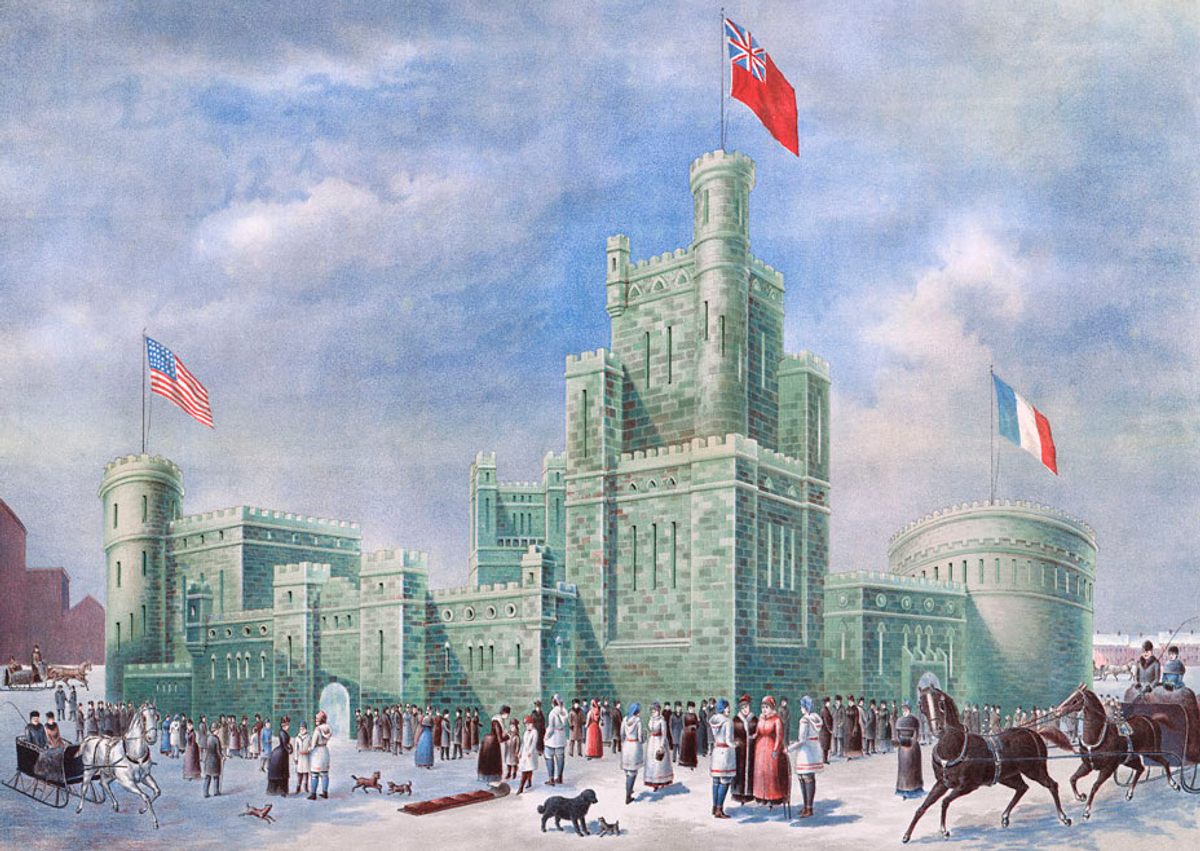

Rising 66 feet from the surface of the frozen Neva River and nearly 165 feet long, the Ice Palace was built “according to all the rules of the most current architecture,” noted Russian mathematician Georg Wolfgang Krafft. And everything, as in everything, was carved from ice. Ice windows, furniture, tables, doors, even playing cards, and everything was painted to look like the real thing. An exact, frigid replica of the empress’s bed chamber, complete with an ice bed, ice canopy, ice pillows, and ice sheets was painstakingly recreated. (Nothing beats snuggling up under a frozen comforter.) Verdant, luscious gardens blossomed from the frozen tundra. Green-painted ice bushes surrounded the palace, and colorful ice birds perched on ice trees. A steam bath, or bania, built from ice sat beside the palace. Decorative ice dolphins blew fire. A life-sized ice elephant’s raised trunk served as a fountain by day and as a stunning torch by night.

The palace was, by all accounts, a marvel. But the elaborate, temporary palace isn’t the strangest part of the story. That winter, Anna ordered a bizarre wedding to take place at the Ice Palace between the disgraced noble-turned-jester, Prince Mikhail Golitsyn, and a Kalmyk woman, Avdotia Buzheninova. In the eyes of many historians, the surreal affair was a defining moment of her reign—one that either condemns it, confirming Anna’s cruelty, or commends it, demonstrating Anna’s shrewd understanding of court politics.

Born on February 7, 1693, Anna Ioannovna or Ivanovna was never meant for the crown. The fourth daughter of Ivan V, Anna, at 17, was married off to a lowly, backwater duke, and was largely forgotten at court. Then the emperor died and the nobility looked far and wide for a puppet they could make ruler. Enter Anna.

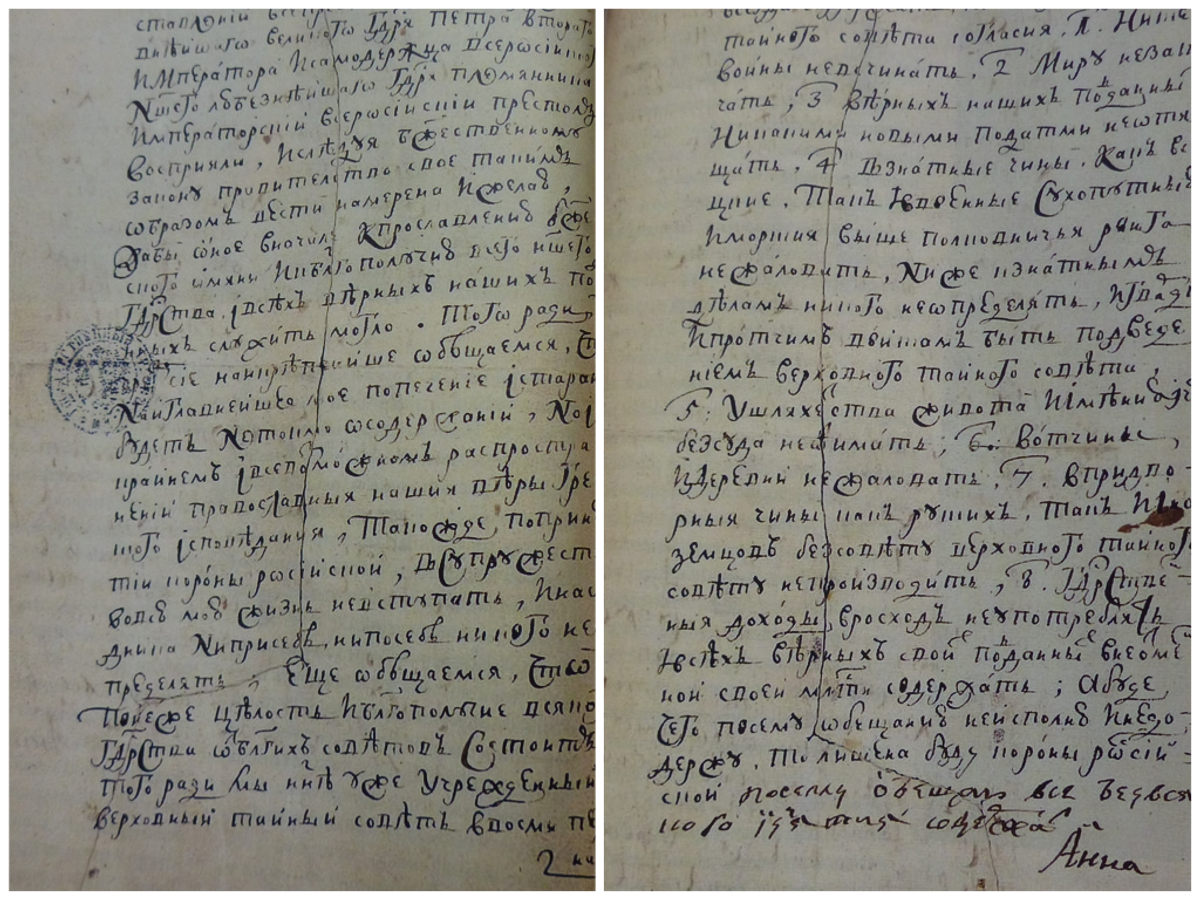

“The nobles choose Anna because, as a woman, they think she’ll be very easily manipulated,” says Russian historian Jacob Bell of the University of Illinois. The nobles imposed a list of conditions (creatively dubbed the “Conditions”) on Anna’s power and made her sign on the dotted line. She signed, but Anna was far smarter than they gave her credit for.

Within a couple of months, Anna solidified support from a group of nobles and the local guards’ regiments. “[She] then, very dramatically tears the conditions in half and declares she will rule in the way she wants to rule,” says Bell. “You can actually go to the archives in St. Petersburg and see this torn-in-half document. It’s actually a thing.” A guard-backed coup d’état was a move that, later, Elizabeth Petrovna and Catherine the Great would copy (minus the paper tearing).

Fast forward almost a decade to 1740. Anna’s reign was in full swing. Continuing many of the efforts begun by Peter the Great, she funded the Russian Academy of Science and encouraged Westernization. She founded the Cadet Corps, a premiere military training school, and maintained a brutal secret police known as the Secret Office of Investigation. She oversaw military victories over the Ottomans and had a great fondness for shooting and hunting, even keeping loaded guns beside palace windows so she could shoot passing seagulls and crows.

Anna’s court was full of fools and jesters, some of whom, like Prince Mikhail Golitsyn, came from noble stock. Before his fooldom, Golitsyn had married a Catholic Italian woman. Catholicism was “a bit of a sore spot,” says Bell, after a Polish pretender to the throne, False Dmitry I, converted to the religion, shunning the Russian Orthodox Church. “There’s a rebellion against him,” says Bell, “and [they] kill him actually and very dramatically shoot his remains out of a canon in the direction of Poland so that he’d go back there.”

When Golitsyn’s Catholic bride died, Anna made the widowed Prince a jester to punish him for having married her. In one jest, he was dressed as a chicken and made to sit on a basket of eggs while clucking. Then, in 1739, she ordered the Ice Palace to be built to celebrate the Russian victory over the Ottomans, and also to serve as a wedding venue for Buzheninova and Golitsyn. Buzheninova was from a Mongolian ethnic group that primarily lived in southwestern Russia, in a region known as Kalmykiya. By some accounts, Buzheninova was an ugly, elderly servant of Anna’s. According to others, she was merely a young woman.

Ahead of the nuptials, Anna decreed every Russian province to send a man and woman wearing traditional dress to attend the spectacle. On Golitsyn and Buzheninova’s special day, nearly 600 indigenous Russian representatives rode through the city on sleds pulled by pigs, moose, camels, and wild boars (the specific animals in attendance vary slightly by source). The inclusion of Buzheninova and these other indigenous Russian peoples was an act of “colonialism,” says Bell, yet another way for Anna to demonstrate her power.

The happy couple followed, riding in a cage strapped to the back of an elephant—subtlety wasn’t really Anna’s style. Then the pair were tucked into the ice sheets of the palace’s bed chamber and left to enjoy their wedding night. Guards posted at the doors ensured the couple wasn’t interrupted, or allowed to escape. The next morning, Golitsyn, supposedly, recounted his night to the delight of Anna and her retinue.

“[The Ice Palace wedding] is just part of the bizarre nature of [Anna’s] reign and of her personality: vindictive, cruel, idle,” says history writer Michael Farquhar, author of Secret Lives of the Tsars. For Farquhar, it’s an episode that feels “uniquely Russian.” “Under the veneer of sophistication was some barbaric behavior,” he says of a Westernizing, 18th-century Russia.

Bell, however, has a different read. “While [Anna’s] reign gets called a ‘dark era,’ it’s because she’s really expanding royal power at the expense of these nobles,” such as Golitsyn. “Put yourself into the shoes of an attendant for a second, you walk into a literal castle made totally out of ice that has just been built on the whim of this woman.” It’s almost as if Anna’s saying, “Look at what I can do. I can literally control the elements, therefore you should serve me,” says Bell. Historian Simon Werrett of University College London even sees the Ice Palace as a demonstration of Russian scientific innovation.

The palace was one of Anna’s last major acts as empress. She died, slowly and painfully, of kidney stones within a year (though, initially, her physicians made the patronizing decision to tell her she was suffering from menopause). Soon after her death, Elizabeth Petrovna, Peter the Great’s daughter, would rise to power, later followed by Catherine the Great in 1762. Both mirrored Anna’s ostentatious power displays, holding, for instance, weekly cross-dressing “metamorphosis balls.” Historians aren’t quite sure the fate of Golitsyn and Buzheninova, but they likely carried on in much the same way they had before their wedding—Golitsyn to jesting and Buzheninova to serving.

Though not the first Empress of Russia, “Anna is important because she is the first Russian Empress to really take control of the reins of state,” says Bell. But even centuries later, scholarship around Anna, Elizabeth, and Catherine “just has a lot of sexist overtones,” he says. In a rendering not all that different from today’s female celebrities, “the empresses are always going to be accused of being superfluous,” of being “party girls” rather than strategic rulers. For Bell, though, all three “were absolutely shrewd, brilliant individuals, who very much ran a massive, multinational, multilingual, bureaucratic empire very effectively for the better part of a century.”

For Bell, “the Ice Palace fits into the reclaiming of Anna Ioannovna because we have to think of her not as this party girl having a good time,” he says, “but rather a very calculating individual who knows how to channel her wealth into respect and into power through these shows of her opulence.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook