The Russian Poetry Scandal That Ended in a Duel

Remembering the Cherubina de Gabriak hoax of 1909.

There is a fine tradition of taking the wind out of the stuffed shirts who run the literary world by tricking them into publishing the work of fictional authors. In the 1940s, an Australian poetry scandal erupted over the invented poet Ern Malley, disgracing the publisher once the hoax was revealed. More recently in the U.S., the wunderkind author JT LeRoy was exposed as a fake persona created by a writer named Laura Albert. But a similar ruse from early 20th century Russia may be the only such literary scandal that ended with two men shooting at each other.

According to an account in the Russian book The Fate of the Silver Age Poets, in August of 1909, Russia’s preeminent literary arts publication, Apollo, received a curious letter. The envelope contained poems written in exquisite handwriting, on perfumed paper, signed only with the Cyrillic letter Ч (che). The unsolicited submission raised the suspicions of Apollo’s de facto publisher and noted Russian art scene figure, Sergey Makovsky, until later that day, when the author called their office.

The woman on the phone identified herself as Cherubina de Gabriak, an unknown poet, looking to find her break in Apollo. Makovsky, who found the mystery poet’s voice quite charming, agreed to publish her work. In the October issue of Apollo, 12 of de Gabriak’s poems were included.

While the author remained a near complete mystery, tidbits of information about de Gabriak emerged through her poetry and correspondence. Supposedly, she was a young girl of French-Polish descent who lived in an oppressive Catholic household, which did not allow her to associate with the outside world. Her admirers caught only glimpses of her life, such as a poem that described her family’s coat of arms, but the riddles surrounding her past just made her all the more alluring. Soon, she was being published in a number of magazines, not just Apollo.

The mystique surrounding de Gabriak created quite a stir among the Russian poets of the day, and a number of Apollo contributors fell in love with her. Most famously, then up-and-coming poet Nikolay Gumilyov, who would go on to become a giant of Russian Symbolist poetry, began a red-blooded correspondence with de Gabriak, writing her a series of love letters.

Not everyone in the scene was quite convinced of the enigmatic poet, however, noting that if she was such a talent, she had no reason to hide.

In November of 1909, it was finally revealed that (as you have surely surmised) Cherubina de Gabriak was a fake persona. In reality, de Gabriak’s true identity was Elizaveta Dmitrieva, a school teacher who had worked with the poet Maximilian Voloshin to scam their contemporaries and get her work noticed. The name Cherubina de Gabriak, was a combination of references to a short story and a wooden imp that Voloshin had once given Dmitrieva. Voloshin was also an editor at Apollo, and knew Makovsky well enough to know what buttons to push to make their character appeal to him.

Dmitrieva had been stricken with tuberculosis at a young age, leaving her with a lifelong limp that made it extremely difficult for her to walk. Her brothers were known to taunt her by tearing one leg off of each of her dolls. Far from being a poet princess cloistered in some far off tower, Dmitrieva was a teacher and studied French and Spanish literature. She had been trying to get her poetry published for some time, including sending unsuccessful submissions to Apollo.

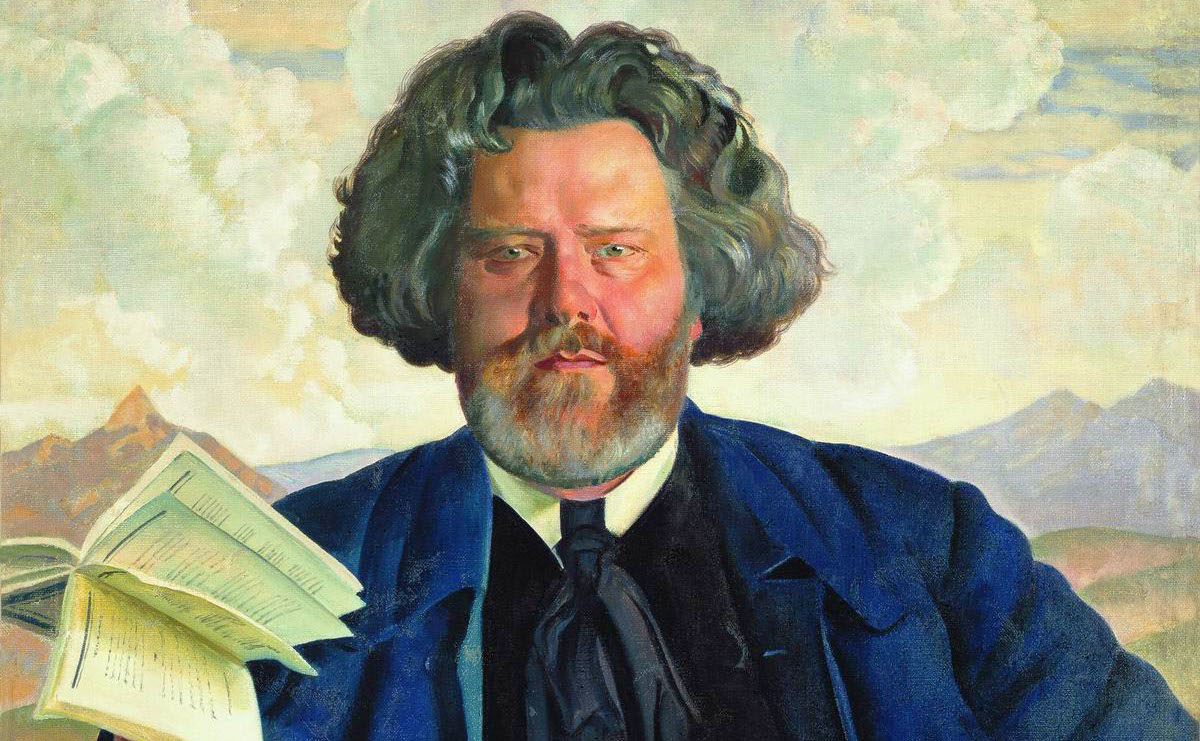

As Voloshin would tell it, when they first met in the summer of 1909, she was writing “simple, sentimentally sweet poems.” But over time, her work evolved. Once the hoax was revealed, many found it hard to believe that Dmitrieva’s talent could have sprung from obscurity, instead choosing to believe that Voloshin must have been the true author. Both Voloshin and Dmitrieva insisted that it was she who wrote the words, while Voloshin edited her (today, it is widely accepted that Dmitrieva was the true author based on comparisons with her later work).

Neither Makovsky nor Gumilyov took the news very well. Both men, embarrassed at having been had, began publicly disparaging Dmitrieva. At one point, Voloshin overheard Gumilyov talking rudely about his affair with Dmitrieva “in the crudest sexual terms,” as 1994’s Dictionary of Russian Women Writers puts it. Voloshin, who was equally enamored with Dmitrieva, decided that enough was enough. He slapped Gumilyov in the face, inviting him to a duel.

Dmitrieva truly did have feelings for Gumilyov, and Voloshin as well. A critical analysis of her poetry from a 2013 issue of The Slavic and East European Journal describes her as “a natural seductress who maintained complex love relations with a number of Modernist poets, and was the cause of the well-publicized duel between Voloshin and Gumilev, both contenders for her heart and hand.”

Gumilyov agreed to the duel, and they met on the shore of the Chernaya River on November 22, near the same spot where the famed Russian poet and novelist Alexander Pushkin had been fatally wounded over half a century earlier. Gumilyov, an excellent marksman, fired at Voloshin but missed, possibly intentionally, and Voloshin’s gun repeatedly misfired. Both men walked away with their lives, though animosity would characterize their relationship for years to come.

Voloshin and Gumilyov went on to become some of the most important Russian poets of their time. As for Dmitrieva, while she continued to write, she was never able to reach the same level of fame during her lifetime as she had when she was de Gabriak.

Today, Dmitrieva’s life and work is finally receiving some much deserved attention. In addition to more academic explorations of her poetry, in 2008, the playwright Paul Cohen unveiled a poorly reviewed stage play based on the story of the hoax, Cherubina. The Village Voice said that it “softened and simplified the story […] bleaching it of much of its nuance and oddity.” Still, critical analysis of Dmitrieva’s work is beginning to place her as a vital member of the Symbolist movement, even if her story will always be tied to the scandal that brought her into the light.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook