Making Salt From an Ancient Ocean Trapped Below the Appalachians

West Virginia was once a seabed.

Each morning, chef-turned-salt-maker Nancy Bruns leaves her home in downtown Charleston, West Virginia, and drives southeast past the domed capitol building alongside the Kanawha River. Past the city, houses thin out and rocky hills rise up on either side of the river. The road passes under Interstate 64 before dropping into the little river-fronting community of Malden. Just outside of the town, Bruns passes her cousin’s pastures, which are full of heritage breed Belted Galloway cattle, and turns into the gravel drive of her company, the J.Q. Dickinson Saltworks.

“I go this way because it reminds me of the area’s history,” says 51-year-old Bruns, her voice calm and measured. “I like to reflect on that history as I prepare for my day. I like to think about my place in it.”

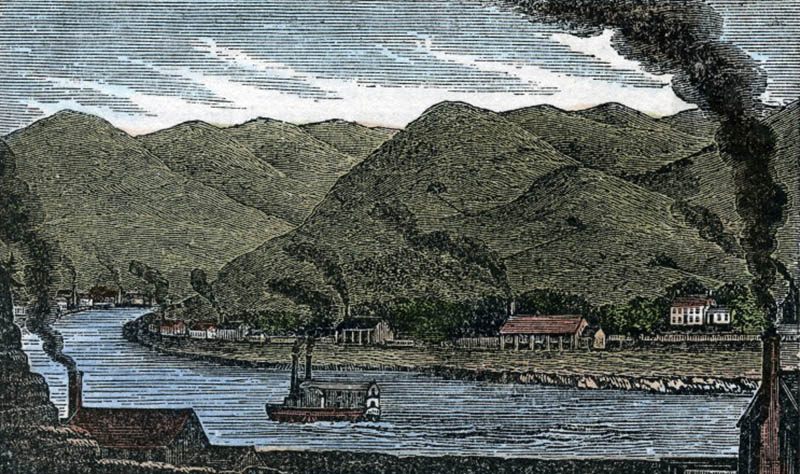

Prior to the Civil War, the area was the largest producer of salt in the United States and known as the Kanawha Salines. At the industry’s peak in the 1840s, it boasted 50 saltworks producing more than three million bushels of salt a year. The land J.Q. Dickinson rests upon has been owned by Bruns’s family for more than 200 years, ever since her four-times-great grandfather, William Dickinson, moved to the area in 1813 with aspirations of making salt. Dickinson’s company became one of the largest and the longest-running of them all, and was active until 1945. After resuscitating the brand in 2013, Bruns and her brother, Lewis Payne, became not only the last remaining salt-makers in Malden, but all of Appalachia.

However, the history Bruns refers to has another component—one that runs deeper than that of America, or even humanity itself. Indeed, the salt contained in the brine her 350-foot-deep wells carry to the surface was formed more than 420 million years ago and hails from the extinct Iapetus Ocean, a body of water that predates the Atlantic.

Our understanding of West Virginia’s salt deposits, which come from a time when the state lay at the bottom of an ocean, is hundreds of years in the making.

“Native Americans were boiling brine to make salt from Kanawha Valley salt marshes long before the first commercial prospectors showed up in the late-1770s,” says Kathleen Counter Benison. An associate professor of geology at West Virginia University,* she specializes in ancient salt formations. “But of course, neither they nor the prospectors knew that salt was vestigial to the Iapetus Ocean.”

According to Indiana University professor Jurgen Schieber, throughout the 18th century, there were still prominent geologists—known as Catastrophists—arguing the Old Testament view that the earth was formed in 4,000 B.C. and subsequently shaped by Biblical events. Jurgen writes that the Uniformitarians, led by Scottish geologist James Hutton (the Father of Modern Geology), had only just proposed “that uniform gradual processes such as, for example, the slow erosion of the coast by waves, shaped the geologic record of the earth over an immensely long period of time.” Speculating the earth was “likely considerably older than 100 million years,” they still believed the Atlantic was primordial.

Although the theory went on to form the basis of modern geology, 100 million years remained the benchmark for subsequent debate until the 20th century.

“The Iapetus wasn’t officially identified until the 1960s,” explains Benison. The first hint of the ocean’s existence came in the early 20th century, when paleontologists in northern Europe discovered fossil evidence that implied two basic things: “That the area had formerly been connected to Appalachia,” but “was separated by a small ocean some tens of kilometers across that predated the Atlantic.”

The findings yielded no satisfactory scientific explanation until the existence of plate tectonics was proved in the early 1960s. The discovery led Canadian geologist John Tuzo Wilson to reinterpret the evidence in 1966, when he named the vanished ocean the Iapetus. (The appellation refers to the father of the Greek titan, Atlas, eponym of the Atlantic.)

“Today most geologists agree the Iapetus was formed around 600 million years ago and lay beneath what is now the eastern coast of North America,” says Benison. “Like the Atlantic, it separated two major continents—Avalonia and Laurentia.” Modern-day West Virginia lay between these two continents, covered by the waters of the Iapetus.

By around 420 million years ago, the Iapetus was gone. Shifting tectonic plates formed the Appalachian Mountains and brought Avalonia and Laurentia together, closing the Iapetus and forming the northern portion of the supercontinent Pangea. After Pangea broke up, the Atlantic opened between Africa and North America.

“But the salt deposits are still here,” says Benison. “If we were to drill down 5,000 feet below the J.Q. Dickinson Salt Works, we’d find vast beds of salt crystals left over from the Iapetus.”

Less concerned with geologic origins, Kanawha Valley salt prospectors of the late-18th century were looking to make money. Military campaigns opened the area to settlement in 1774. Lured by an account of Shawnee Indians making salt by boiling brine along the banks of the Kanawha River, Elisha Brooks erected the Kanawha Salines’ first salt furnace in 1797.

At the time, the mineral was a scarce domestic commodity that had to be purchased from overseas. The further you were from the East Coast, the more expensive salt became.

“With the Kanawha being a tributary of the Ohio River and thus the Mississippi, the salt-makers were in a position to supply both the emerging meat-packing industry of Cincinnati and residents of Spanish Louisiana—whose main business was livestock and selling cured meat—with salt,” says Kanawha Valley historian Carter Bruns.

Much like later oil booms, vast fortunes stood to be made. Prospectors flocked to the area and imported thousands of slaves to fuel development. As a result, ancillary industries sprang up.

“Hundreds of men worked in cooperages creating the white oak barrels into which salt was packed for shipment to the Ohio River Valley and beyond,” says Bruns. “Others worked as boat builders, creating the flat-boats that carried the mineral downstream. Hundreds more worked as carpenters maintaining the salt-making facilities that included sheds, troughs, pipes and sluices, scaffolds, docks, and warehouses required for the growing industry.”

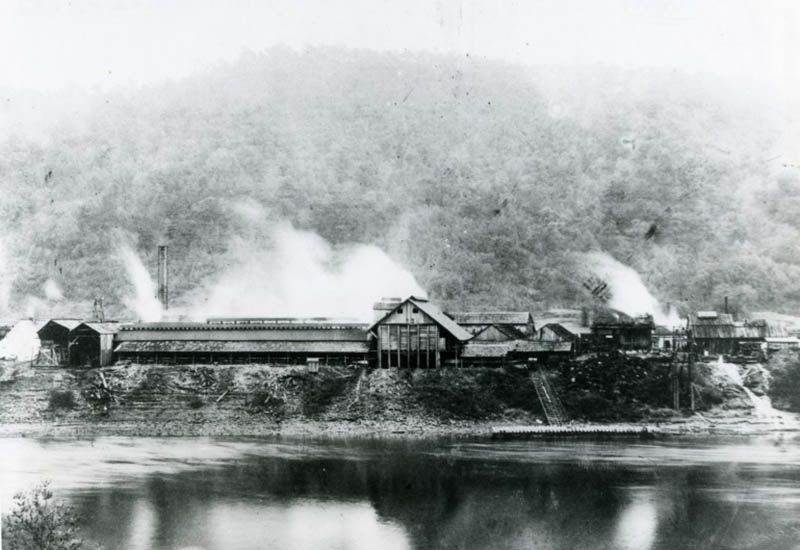

According to a report compiled by Jane R. Eggleston for the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey, by 1808, David and Joseph Ruffner had installed the Salines’ first brine-water well, drilling to a depth of 59 feet. The unit enabled the brothers to produce salt more efficiently and in greater quantities than before. “A younger Ruffner brother, Tobias, suspected that a vast saline reservoir existed under the Kanawha Valley and, drilling to a depth of 410 feet, tapped an even richer brine,” writes Eggleston. “This discovery set off a veritable frenzy of drilling, and by 1815, there were 52 furnaces in operation.”

Nancy Bruns’s and Payne’s own patriarch, Colonel John Dickinson of Bath County, Virginia, fought against Native Americans in the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774 and received 502 acres along the Kanawha River as compensation. His son, William Dickinson, established the family’s first salt well in 1817. Dickinson went on to become the largest salt-maker in the valley.

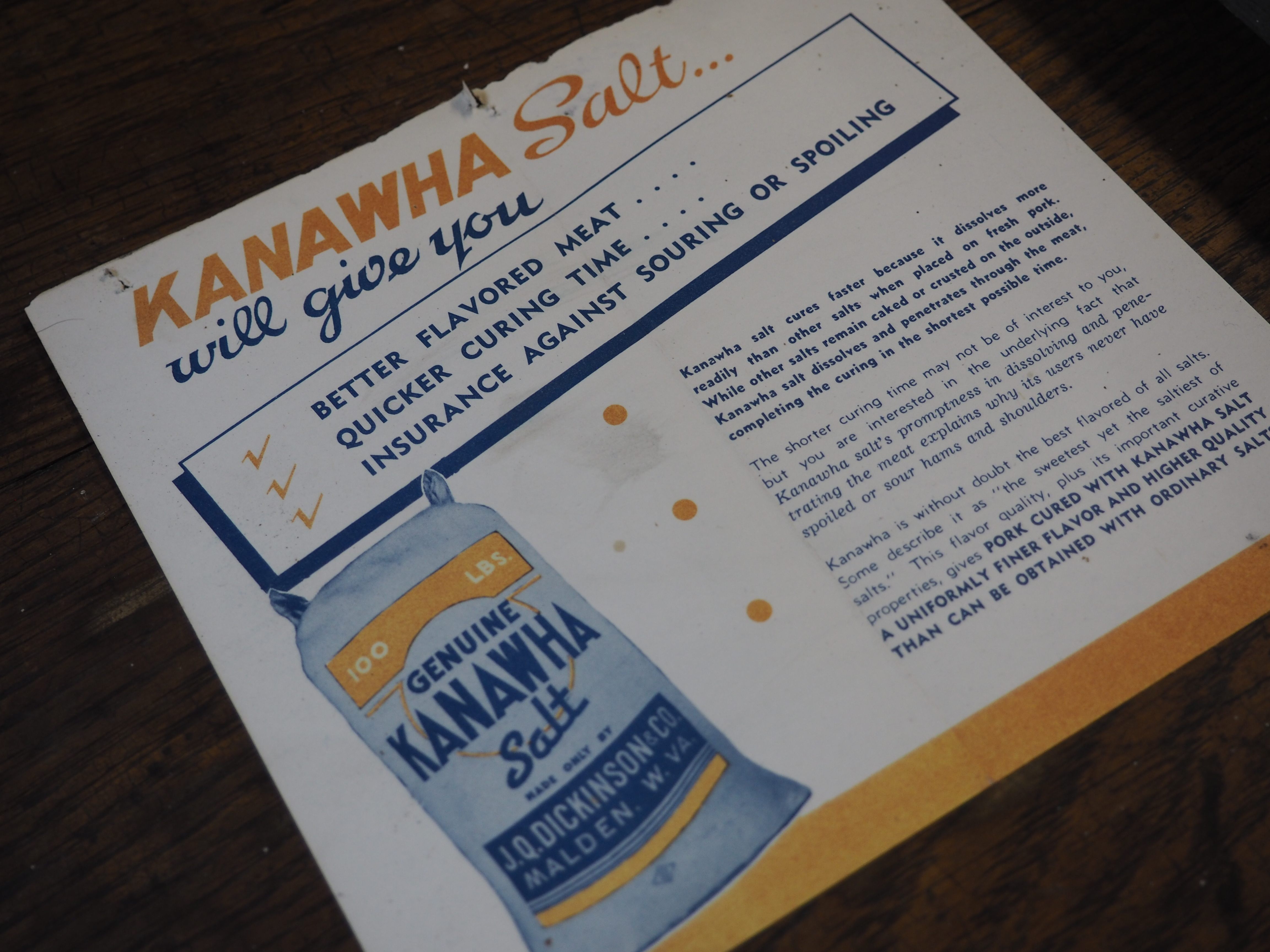

In 1851, at the World’s Fair in London, the Great Kanawha Salt was deemed The Best Salt in the World. “At that time,” writes Eggleston, “the Kanawha Valley was one of the largest salt manufacturing centers in the United States.”

Then came the fall. In 1861, the Kanawha River flooded. The catastrophe was followed immediately by the Civil War. Crippled by back-to-back blows and competition from more efficient operations in the western United States, by the late 1800s, the Dickinson’s Malden furnace was the lone survivor of the great Kanawha salt industry.

Although Bruns and her brother grew up in Charleston, West Virginia, on land handed down from John Dickinson himself, they knew nothing of their salt-making heritage, much less the Iapetus Ocean. “By the time we were coming up, it wasn’t something people talked about,” says Bruns. “It was basically a forgotten history.”

After earning a degree from the New England Culinary Institute, Bruns settled in the mountains of western North Carolina, where she pursued a 20-year career as a chef and restaurateur. It wasn’t until her former husband entered graduate school in 2008 that she learned of the J.Q. Dickinson Salt Works. As a candidate for a master’s degree in American History, his thesis was titled, of all things, “The Antebellum Industrialization of the Kanawha Valley in the Virginia Backcountry.”

“He’d gotten interested in the area where I grew up and, when he started doing research, discovered my family had been in the salt-making business,” says Bruns. “That was the first I’d ever heard of it. I wanted to know more.”

Learning about her forebears revealed a fascinating but troubled history. Of course, the Kanawha Valley salt-making industry had been built largely on the backs of slaves. Brun says she appalled by that aspect of the J.Q. Dickinson legacy. “We disagree with and even abhor some of the choices our family and country made, and don’t try to sugarcoat any of it,” she says. “But we also choose to celebrate their achievements and take pride in what they were able to accomplish.”

By 2012, Bruns’s interest in the former salt-works had blossomed into an inchoate business plan. Consulting with a geologist friend, she discovered two things. First, the source below the family’s land would still produce brine. Second, if she made salt, it would derive from the Iapetus Ocean.

“It felt like all the tumblers had just fallen into place,” says Bruns. “I knew that regionally sourced, small-batch, artisanal foods were in demand. And here we already had this rich family history. On top of that, my friend was telling me our salt would come from a protected source that had never been touched by humans. It was so surreal. I knew we had to do it.”

Partnering with her brother, Bruns moved home and revived the J.Q. Dickinson brand. The company drilled its first well in the spring of 2013 and installed five hoop-houses for solar evaporation shortly thereafter. By 2014, Kanawha Valley salt harvested from the Iapetus Ocean was once again available for public consumption. As Bruns had hoped, the product took off, selling out within three weeks. Today, the company hand-harvests around 6,000 pounds of salt a year and has wholesale accounts with more than 120 chefs and specialty food shops.

But more than a narrative-driven artisanal novelty, the salt is distinguished by its taste.

“The minerality from millennia of stone erosion elevates this salt above other sea salts I’ve tasted,” says Ian Boden, a 2013 and 2017 James Beard Foundation Best Chef in America semi-finalist. In his hyper-local Staunton, Virginia, restaurant, The Shack, Boden uses J.Q. Dickinson salts for finishing as well as for making miso and gochujang. “I love how the coarser product gives bright pops of salinity and crunch, and adds depth to meats and vegetables.”

For Boden and other local-foods-oriented chefs, that historical depth of flavor imbues dishes with an extra something special, and is worth the $25-a-pound price tag. “If you think about it, Nancy’s salt is the oldest regional taste-product in Appalachia and probably the whole world,” he says. “To me, that fact alone makes it a pretty magical ingredient to serve.”

*Correction: This post previously described Kathleen Counter Benison as an associate professor at the University of West Virginia. In fact, the university is called West Virginia University.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook