The Cartographers Who Put Water Where It Didn’t Belong

From a distance, European mapmakers documenting North America often perpetuated strategic myths of oceans, lakes, and rivers.

To hear Admiral Bartholomew de Fonte tell it, his voyage was full of serendipity and promise. In a 1708 edition of the English periodical The Monthly Miscellany or Memoirs for the Curious, de Fonte recounted a journey, some five decades prior, “to find out if there was any North West Passage from the Atlantick Ocean into the South and Tartarian Sea.” He had shoved off from Lima, he wrote, and navigated to the present-day Pacific Northwest, where he entered an intricate system of watery arteries that beckoned him inland.

He chronicled one fortuitous scene after another. Nudged along by gentle wind, he floated into a lake he christened Lake de Fonte. It was 60 fathom deep (roughly 360 feet), and “abounds with excellent cod and ling, very large and well fed.” The water was also speckled with islands thick with cherries, strawberries, and wild currants. The land was shaggy with “shrubby Woods” and moss, which fattened herds of moose.

His tales were full of plenty—lush land, well-stocked seas—and they were also totally apocryphal. There’s no proof of the voyage, or of the character of de Fonte himself. The whole saga, excerpted in the historian Glyndwr Williams’s book, Voyages of Delusion: The Quest for the Northwest Passage, was later attributed to the magazine’s editor.

When plotting out their maps of North America, many 18th-century European cartographers relied on accounts that drifted across their desks. These were a collage of nautical references, local lore, missionary dispatches, and more. Since it wasn’t always possible to fact-check these observations, even maps by the most conscientious makers could be sprinkled with errors. Some of these incorrect annotations were aspirational—and many of them had to do with waterways.

Say that de Fonte had indeed, as he claimed, passed a ship that had sailed inland from Boston. That would have been proof of a viable route through the Northwest Passage, which would have been a major boon to British and French traders. This type of passageway, or other interior waterways like it, would have been so convenient, in fact, that a number of cartographers seemed to will it into being by putting it on paper.

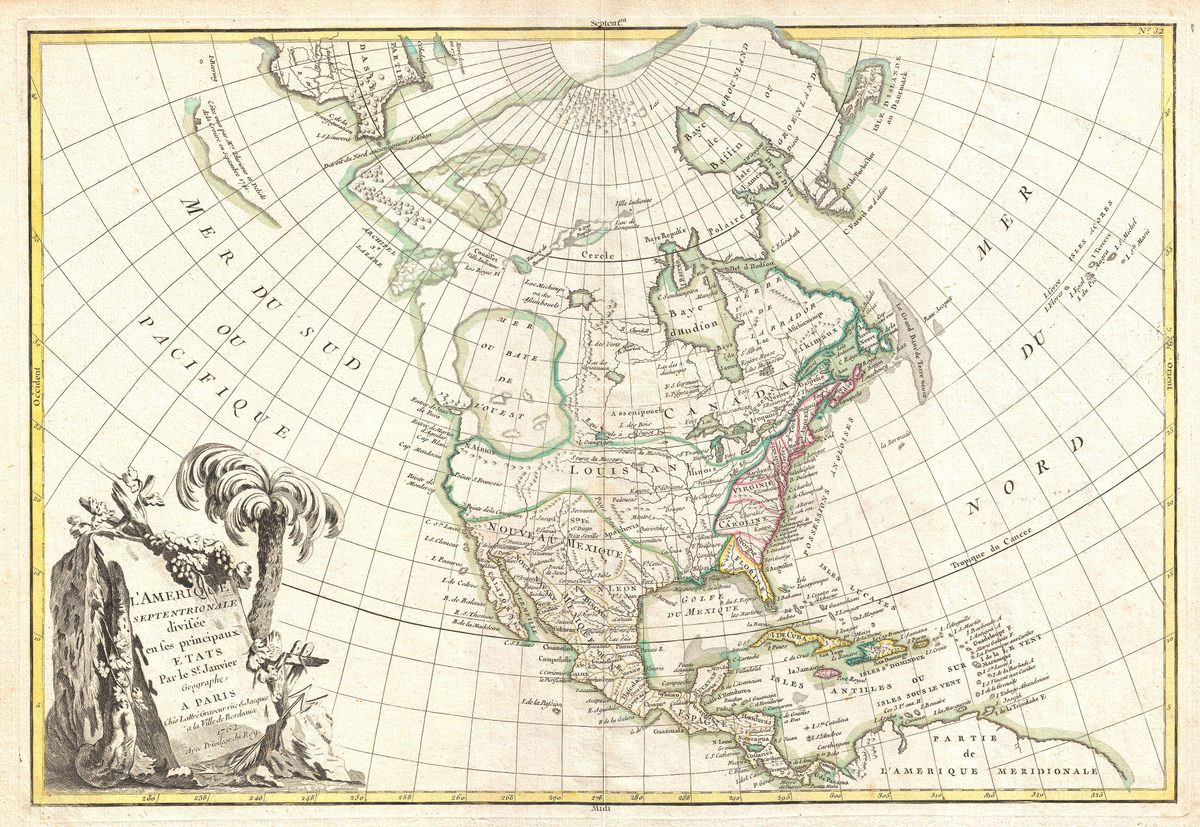

Kevin James Brown, the founder of Geographicus Antique Maps, traces the notion of an inland sea to the 1500s, when the Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano spotted the sounds abutting North Carolina’s Outer Banks and assumed he was looking at an ocean. This sea dried up from maps within a few centuries—just in time to make way for an inlet or strait described in another (potentially fabricated) narrative of the explorer Juan de Fuca’s voyage. The Sea of the West (or Mer de la Ouest), a later and larger speculative sea occupying much of the present-day West Coast, gained traction in the work of the cartographers Guillaume de l’Isle and Philippe Buache.

By the early 18th century, writes Brown, cartographers were combating the problem of patchwork knowledge by plugging in best guesses—drawn from science and geographic patterns—“to fill in blank spaces when little else was known.” The Sea of the West “is the perfect example,” Brown writes. “Though a salt water inlet from the Pacific had long been speculated upon and hoped for, Buache and de l’Isle embraced the theory because it supported both the ambitions of the French crown in the New World and the theoretical geographic theory that Buache was developing.” It was a speculative addition—and a strategic one.

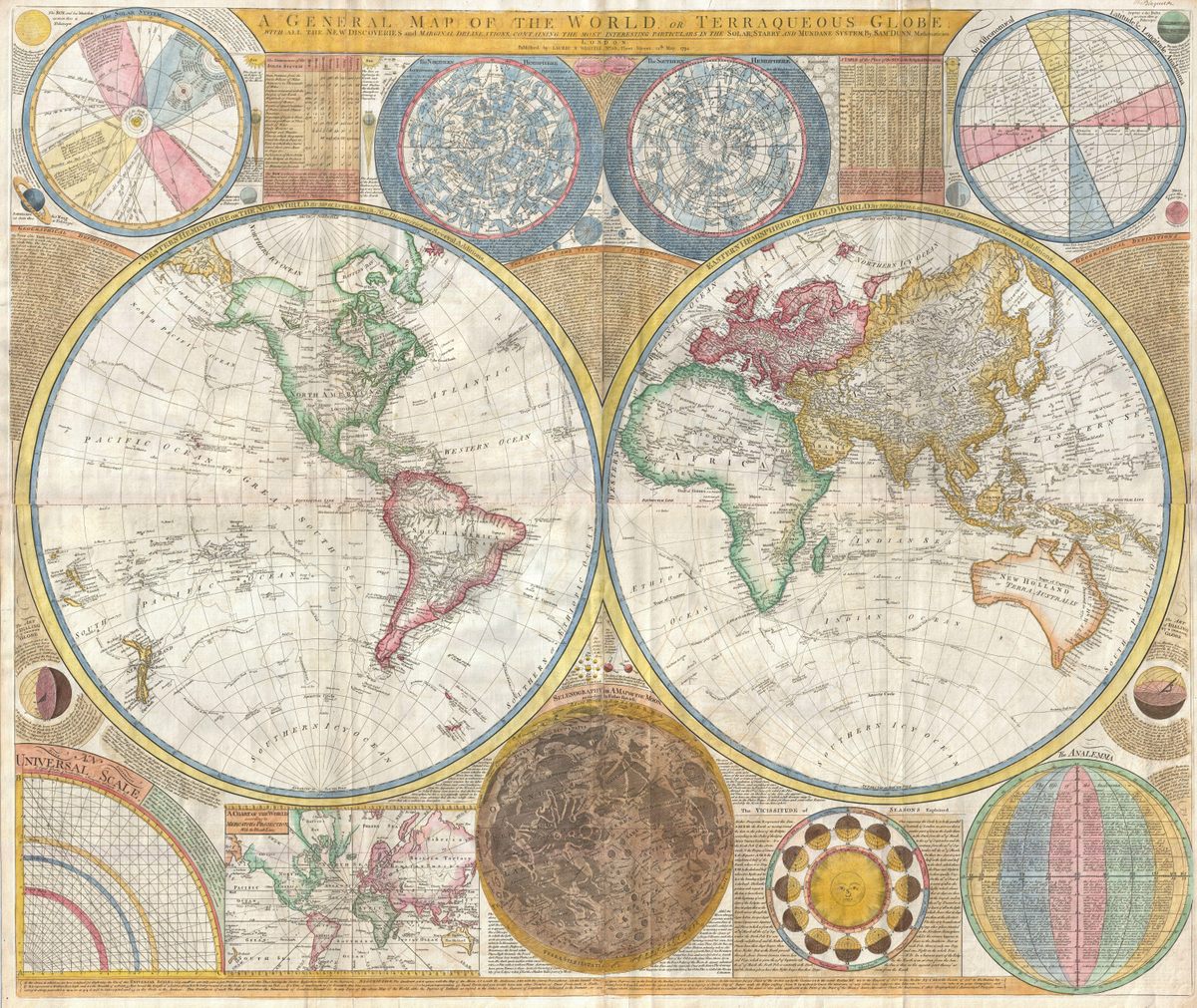

Ditto the the River of the West, an apocryphal route that meandered from the middle of the continent to its western edge. Two different potential routes are suggested on this 1794 double-hemisphere map by Samuel Dunn.

These features disappeared from maps soon after, as expeditions got an in-person look at the geography and dismissed the more fanciful additions. Now, they linger as reminders that maps don’t only recount geographic traits, but also the aspirations (politically, economically, and otherwise) of the people who plot them.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook