This Connecticut Inn Has Hosted Sea Chantey Singalongs for Half a Century

Landlubbers are very welcome.

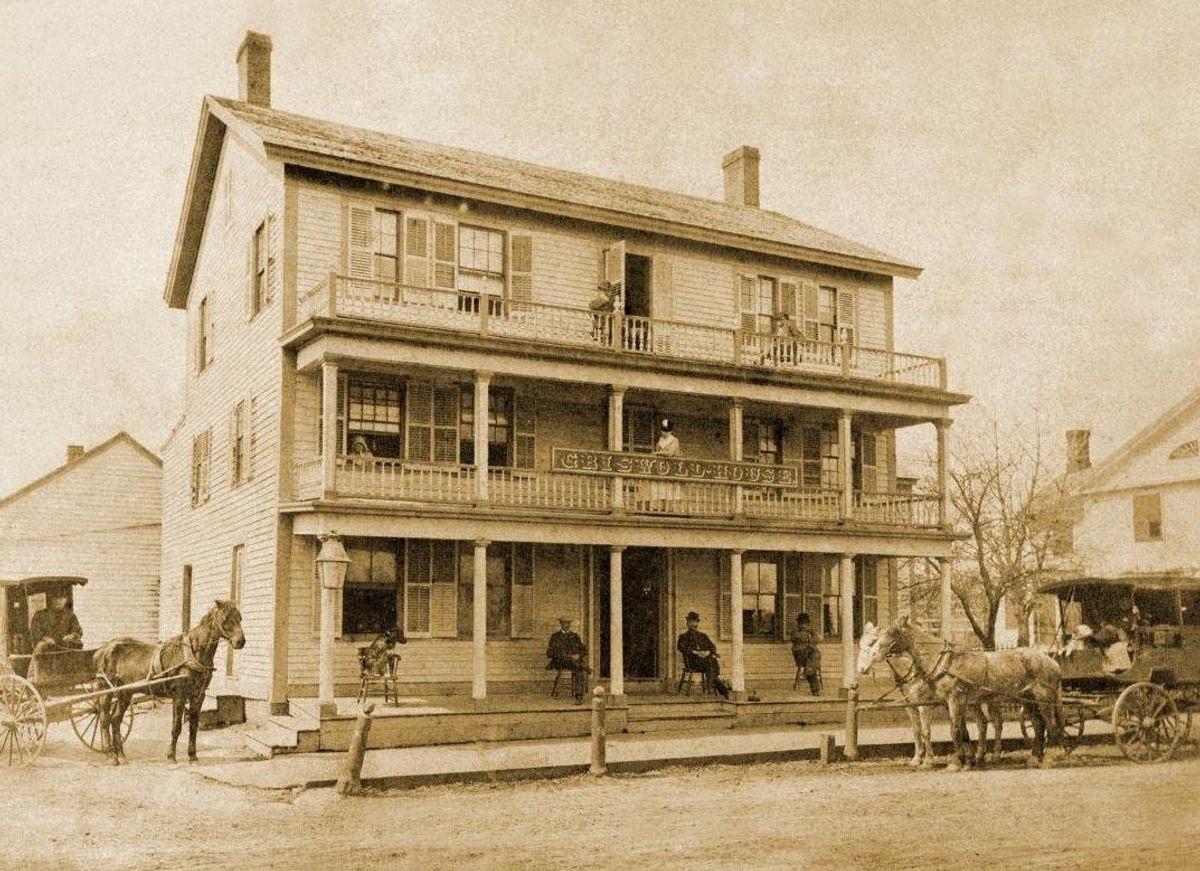

On 8:30 p.m. on any given Monday before the pandemic, The Griswold Inn would be packed. A stately colonial building in the sleepy, coastal New England town of Essex, Connecticut, the Griswold Inn sits just steps from the water. Flying gallantly above the sidewalk was a flag featuring an anchor and the phrase “Chanteys tonight!” Small groups would huddle outside the Inn, finishing cigarettes or sipping Guinness in the breeze blowing in off the Connecticut River while, inside, throngs of people packed the front room. Young, old, regular, first-timer, salt-crusted, landlubber—they all crushed together at the bar and fanned around the central heater and precariously mounted Christmas tree, which is on view all year and redecorated for each season. Four musicians strummed their instruments, warming up as one frantic server weaved her way through the room, filling the drink orders she knew by heart.

Packed with framed documents, photographs of old riverboats and steam ships, even an entire oar from the whaling ship Charles W. Morgan, moored just a few miles away in Mystic Seaport, the walls of the Griswold Inn give the place a sense of an historical exhibit. The artifacts are homages to the area’s seafaring, shipbuilding, and river-faring traditions—and many locals dock themselves at the bar, week after week, to sing about them, beating the washed-up TikTok trend by several decades.

Welcome to Sea Chanteys at the Gris, a weekly tradition since 1972. Cliff Haslam, who started the event nearly 50 years ago, is accustomed to standing at the front of the room shouldering a large, twelve-string guitar. After a few words about the importance of canal boats and canal workers, he once launched into “Shove Around the Jug”—a folk song with origins in Maine that describes the allure of the women from a particular town on the Erie Canal— and the entire room joined him for the chorus. Powerful, full-throated chords built of open harmonies make the notes easy for even the roughest voice to find, and the lyrics repeat so often that, by the end of a song, a newcomer can belt as enthusiastically as someone who has been attending for years. The sung stories are embodied, paired with dances, coordinated claps, or stomps: This is full-body storytelling, with a melody.

Starting with a repertoire that was as much English, Irish, and Scottish folk songs as it was sea music—with its subgenres of chanteys, forebitters, and whaling songs—Haslam performed solo at the pub for over 10 years before he invited some of his regular patrons to join him onstage. One, Joseph Morneault, played whistles in the crowd and then in the band, eventually playing mandolin, mandola, banjo, and concertina, too. The regulars who became the band dubbed themselves the Jovial Crew in the mid-1980s, and the current incarnation of the lineup, featuring Tim Marth and Rick Spencer as well as Haslam and Morneault, has been playing together for the last decade.*

Bob Stepno, a former Jovial Crew member, recalls finding out about the chantey nights by chance and proximity. When he moved to Essex in 1988 to work at a newspaper devoted to boating, the flag advertising chantey night was hard to miss, he says. He’d been hanging around folk music nights at various coffeehouses since the 1960s, so when someone brought a mandolin to the Gris one night, he picked it up. “I gave it a few strums and Cliff [Haslam] immediately invited me to bring mine down,” he says. The band’s lineup has changed over the years, with Haslam as the constant anchor. The repertoire now includes sea music, folk music, ballads, and the occasional dirty song, saved for the third and final set of the evening.

Sea chanteys were designed to aid sailors in their work pushing and pulling assorted items on a ship. While often lumped together with anything sung about—or aboard—18th-century vessels, chanteys are work songs whose purpose was to mark and coordinate collective pushing and pulling aboard the ship, such as raising or lowering an anchor. (The Wellerman song that recently made the rounds on TikTok isn’t really a chantey, because it’s not a ship work song so much as a ballad about a ship supply company in Australia, the Weller Brothers. At best it could be what’s known as a ‘cutting-in’ chantey, sung while relieving a whale of its blubber.)

Sam Haller, a chantey-night regular and a former deckhand on a three-masted topsail schooner, understands the music on a visceral level because he worked on one of the types of ships often referenced in the songs. The vessels had always fascinated him, but working as a deckhand and bosun (from “boatswain,” effectively deckhand-in-chief) changed his relationship with them. “It was dangerous, tough, work,” he says. “We were readily injured….It was not a singing ship; it was a praying ship.” Though he didn’t sing, Haller’s work helped him understand the perspectives in the tunes. “These are songs about working a dangerous, low-paying job far from everything that you know, waiting to go to shore and get drunk,” he says.

Haller also finds that the local historical context adds to the experience at the Gris. “To be doing something like this in a place like Essex, at the Griswold Inn, is tremendous,” he says. “Essex was famous for shipbuilding—these little New England towns are dependent on keeping that historical experience alive. You feel the history in these places.”

Gris regular Ben Parker, an origami artist, also found fellowship at chantey nights. He visited for the first time in 2011, with several friends, and kept going back. “You see the regulars, or the folks who come every other week, or the summer people, or the winter people,” he says. “Despite being disparate groups—a whole range of demographics—we all got along.” Though he doesn’t have a musical background, he found that he really dug the songs, and liked the challenge of memorizing them. He now keeps a notebook of songs he’s practicing or would like to learn, and he found that chantey nights buoy his spirits. “I could go to the Gris in celebration or to drown in sorrows,” he says. “It was cathartic.” When he found himself out of work a few years ago, the chantey community felt mooring. Parker says that he “went out to the Gris, got drunk, sang, and then felt better the next day.” After losing another job during the COVID-19 pandemic, when chantey nights were paused, he adds, feeling better “took a whole lot longer.”

While the pandemic rages on, Parker and a few other key Gris regulars created a weekly, invite-only Zoom called the “Has-Beens Sing,” with each individual sharing a ballad in turn. The rest of the community has largely migrated to a Facebook page, “Sea Chantey Regulars.” Already robust, it also saw a considerable bump when chanteys surged in popularity on TikTok, and membership is now nearly 800 strong. But devotees look forward to an in-person return to the Gris as soon as possible. Facebook pages are great for sharing links, and Zoom meetings keep people in touch, but since it’s hard to sing together over a crowded call, everyone winds up singing alone—a vast departure from the collective crooning they once shared at the Gris on Monday nights.

That’s where Haslam has serenaded generations of regulars. “There’s people we’ve met who get married and have kids and then their kids show up and say that their grandfather used to show up,” he chuckles. “I guess that’s my legacy: introducing people to this music, and having a good night singing along.”

*Correction: This post has been tweaked to clarify when the band started going by the name “Jovial Crew.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook