A Secret Note Hidden in an 1800s Dress Has Been Decoded

A team explores insights about Victorian life and who the woman might have been.

When Sara Rivers Cofield found a rust-colored 1880’s bustle dress in a Maine antique mall a decade ago, she had no idea she would unearth a puzzle that would stump cryptographers across the globe. As an archaeologist for Maryland’s MAC Lab, Rivers Cofield has long been interested in historical fashion as a hobby—she began collecting antique bags at age 12. She’s found a few forgotten items in purses, like a wheat penny and a pendant, but says, “This is the first time I ever found anything in a dress, and most of the dresses that I have don’t have pockets.”

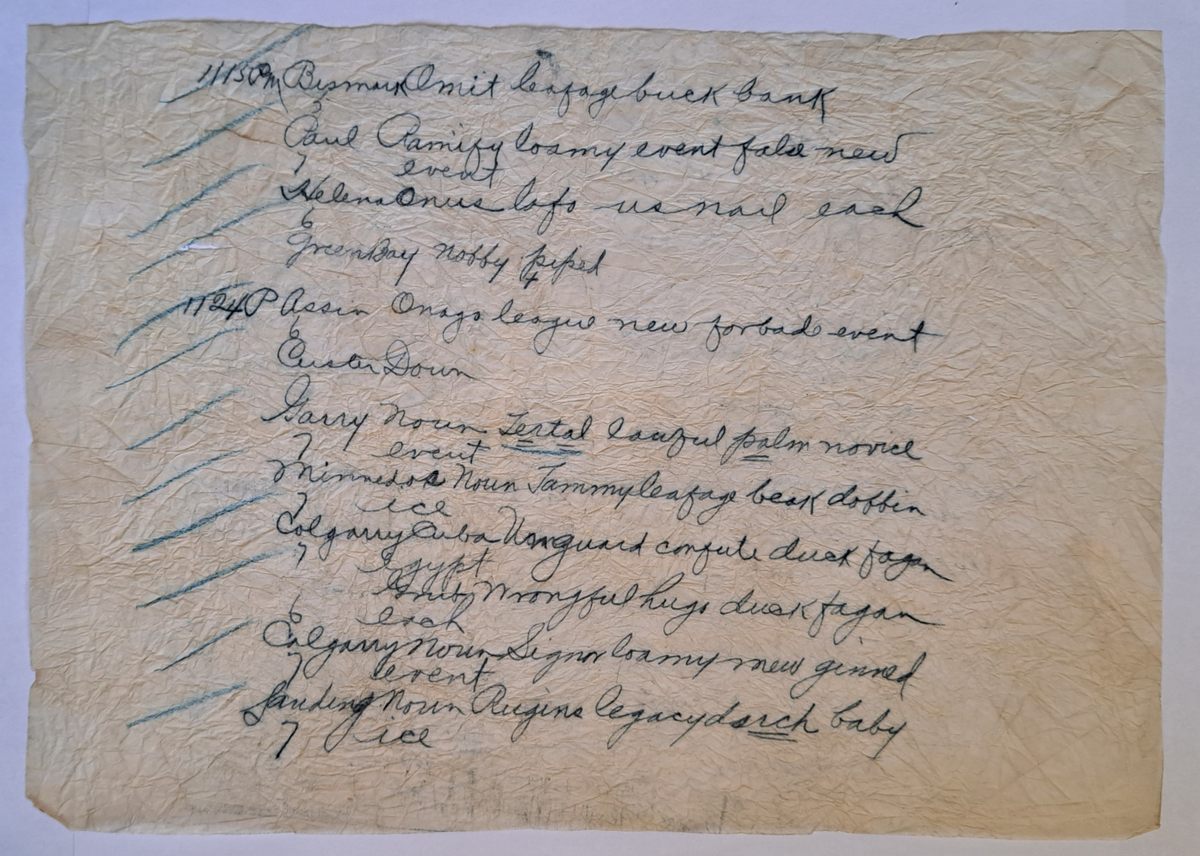

Tucked amidst layers of silk, Rivers Cofield found a hidden pocket with a note that seemed nonsensical. “Helena onus lofo us nail each / Green Bay nobby piped,” read one line. Posting the dress to her blog, she asked readers to rise to the challenge. Bloggers listed it among the top 50 unsolved codes in the world, and many took a stab at it.

Finally, Canadian hobbyist Wayne Chan solved the mystery in 2022, publishing his findings in 2023. While not espionage or international secrets, that cipher contained coded information that did in fact change daily life in North America.

Chan is a coding hobbyist, and he focused on the 1800s note during holiday breaks from his job at the University of Manitoba. As a computer analyst with the Centre for Earth Observation Science, he’s long been interested in patterns and coding. While initially certain this was a telegraph code, it took nearly four years—and 170 code books—to figure out which one.

By examining the data listed, Chan deduced that these messages were sent to the United States Signal Corps on May 27, 1888. The Signal Corps eventually became what is today’s National Weather Service, an agency of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA]. And the note contains a series of shorthand weather report telegrams sent to that central reporting location in Washington, D.C.

The ability to predict the weather was one of the most revolutionary advancements in American life after centuries of being ravaged by surprise storms or losing crops to unexpected freezes. “People often ask me if I was disappointed it was ‘just the weather,’” says Rivers Cofield, “But my whole career is about studying everyday life through trash people left behind. This was more revealing about everyday life in the 1880s to me than any other collection I’ve worked with, archaeological or antique fashion. It’s a much bigger picture than any one-off secret intelligence transaction.”

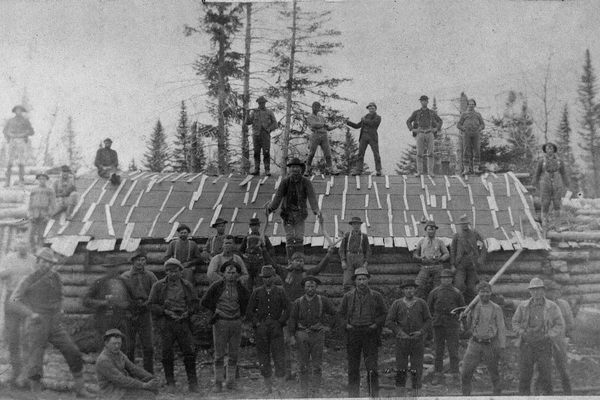

Humans have really only begun to understand and track weather patterns in the last 150 years, says Alison Gillespie, public affairs specialist for NOAA’s research division. Before the telegraph, people relied on observations and lore like “red sky at night, sailor’s delight” to gauge the weather, but it was far from accurate. Devices to record data—like barometers, dew point calculators, and gadgets to measure wind speed called anemometers—were perfected during the mid 1800’s. “There was so much interest in trying to understand the nature of weather,” says Gillespie. Volunteers around the country recorded weather observations as patterns began to emerge. “Citizen science was happening in that period, and it grew into the whole field of meteorology.”

While official weather reporting only began in 1880, the invention of the telegraph in 1837 inadvertently began to provide the clues needed to launch the field of meteorology, Chan found in his research. Telegraph operators began to associate downed lines or reports of rain to the west as an impending sign of what weather they could expect next—a novel concept at the time.

“Around 200 weather stations in the U.S. and Canada would transmit their weather observations at least three times a day,” says Chan. Within three hours of reporting to the Smithsonian, weather maps were drawn, sent to the press, and posted in public spaces. The six-word messages relayed the city, barometric pressure, dew point, temperature, cloud cover, and wind direction and velocity. Day after day, laypeople transmitted the weather while scientists worked hard to predict its patterns.

These messages were so important, wrote Chan in his paper, that telegraph lines to D.C. were left open during transmission windows so no weather reporting was missed. Coding the data made the per-word cost of frequent telegrams feasible.

Humans have long been interested in disguising messages for many reasons, says Dr. Andrew Hammond. He’s a historian and curator at the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C. and says that from NSA employees to hobbyists, the appeal is the mystery. “People become interested in this for a variety of reasons, but quite often people just enjoy the challenge of breaking or cracking a puzzle.” As to codes in clothing? It’s not uncommon.

“Codes have been hidden in all manner of clothing and accessories—hats, watches, shirts, trousers, shoes, you name it. Almost anywhere that has a decent chance of successfully concealing a code may be brought into play,” says Hammond. He cites examples including stitching that contained Morse code during World War II and a more recent occurrence where exploited textile workers hid messages inside clothing.

Gillespie says that her organization has many artifacts and exhibits about the history of meteorology, but this particular find has fascinated NOAA. “What sets this one apart is that it was a little bit forgotten, the role of the telegraph, and then you put a mysterious person in a beautiful dress into it—that really brings it to life for a lot of us.”

Wayne found 18 women who may have worked at the organization that predated NOAA at that time, and narrowed down who he felt would have a dress this fancy based on their job and station in life. The dress had a name tag, Bennett, but that name doesn’t match up with his list. River Cothen speculates that it was a wife of a male telegraph worker and she found it doing laundry and saved it because paper was precious—perhaps even for a baby wipe, as one of the women they found was pregnant at the time. However, though the theories were fascinating and well-researched, ultimately the hypotheses are conjecture at this point, and nothing can yet be proven.

Rivers Cofield was always all about the dresses, but says she is now fascinated by her newfound knowledge of weather reporting. From home barometers she’s uncovered when excavating homesteads to today’s satellite images, being able to forecast the weather was revolutionary. “I don’t really care what the weather was on May 27, 1888,” she says, “but it is hugely impactful to think about how people’s lives changed at that time.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook