Sold: A Pigeon, for $1.4 Million

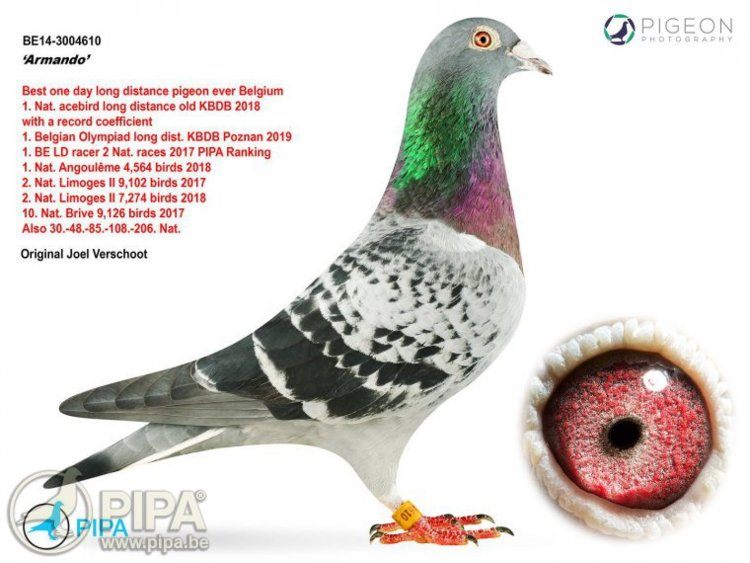

Meet Armando, a champion racer.

In many cities around the world, feral pigeons are a dime a dozen. They roost on roofs, they coo from wires, and they peck outside bakeries, waiting for day-old handouts. Pigeons that are domesticated and bred for racing are birds of a fancier feather—and one buyer recently shelled out $1.4 million to add a little guy named Armando to their roster of winged competitors.

The Belgian breeder Joël Verschoot put Armando up for sale on the pigeon auction site PIPA, where several bidders scrambled to nab him. When bidding closed on March 18, 2019, Armando’s price had inched above €1.2 million (more than $1.4 million, in U.S. dollars). Seven of Armando’s offspring were also up for sale, and they’ll fan out across Belgium, Turkey, Germany, The Netherlands, and China. Armando will be heading to China, too, where the sport of pigeon racing has boomed in recent years. On the mainland, where most forms of gambling are prohibited, pigeon racing gets a pass, and there are at least 100,000 pigeon breeders in Beijing alone, CNN reported.

Many wildlife groups and rehabilitators are fundamentally opposed to pigeon racing, arguing that the birds face a barrage of challenges before, during, and after the events, which sometimes span hundreds of miles. “We think this is a flawed situation right from the beginning,” says Elizabeth Young, founding director of Palomacy, a pigeon rescue organization in the San Francisco Bay Area. Young’s group works with domestic pigeons who find themselves in the wild, including ones that were grounded during races, often because they were struck by hawks, outmatched by the wind, or ran out of energy.

From a purchaser’s perspective, this bird had several things working in his favor, says Tim Heidrich, secretary of the National Pigeon Association, a bird fanciers’ group. Armando has already soared past the competition in several long-distance races, and delivered sterling performances in Belgium, Heinrich says, where competition is stiff. Selecting a racing pigeon can be similar to selecting champion dogs or thoroughbred race horses, says Deone Roberts, sport development manager at the American Racing Pigeon Union. “Pedigree can be important for the owner who may be hoping for genetic transmission of the most desired qualities,” Roberts says. Armando is also young enough to be bred several times over the years, Heidrich says, “thus maximizing the investment in him.”

While other top birds have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars in the past—and despite Armando’s bona fides—“I think the price got very much out of hand,” Heidrich writes in an email. “You probably had a couple of billionaires bidding with their egos instead of their brains.” Still, Heidrich adds, “Like a great race horse, he’s worth what someone is willing to pay.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook