How Soviet Children’s Books Became Collectors’ Items in India

Thanks to nostalgia, the literary legacy of the USSR has a long afterlife.

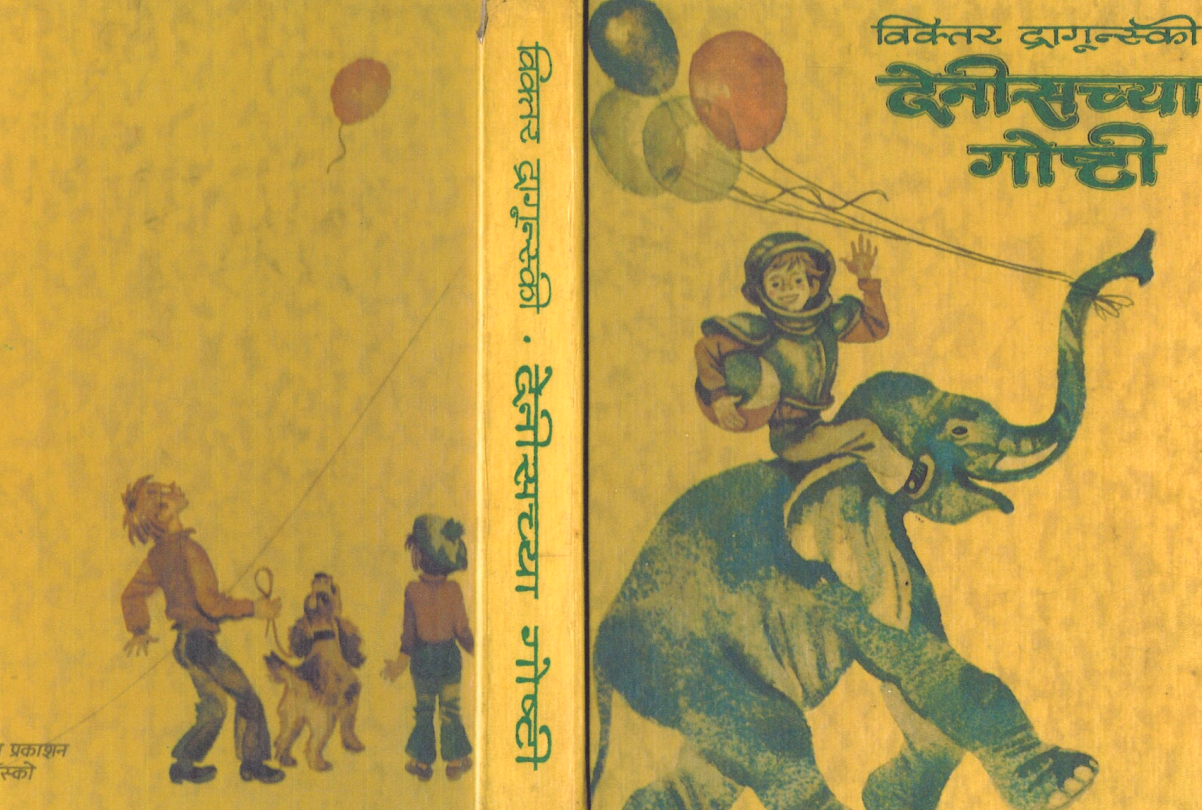

When he was about nine or 10 years old, Devadatta Rajadhyaksha read the book The Adventures of Dennis, by Victor Dragunsky. Rajadhyaksha was mesmerized by naughty little Dennis, who kept grass snakes, lizards, and frogs in his pockets, made funny faces in front of the mirror, and liked to hop and skip. The book was originally written in Russian, but Rajadhyaksha read the book in his mother tongue, Marathi, as Dennis Chya Goshti.

Rajadhyaksha is now in his forties, and the book is still a favorite. Now an accountant in Maharashtra in central India, Rajadhyaksha collects Soviet-era books translated into Marathi. He is active on a Facebook group that celebrates, preserves, and promotes the books, and he and fellow book lovers Nikhil Rane and Prasad Deshpande produced a documentary on Soviet books in Marathi titled Dhukyat Haravlele Laal Taare (Red Stars Lost in the Mist). “These books lit up our childhood,” Rajadhyaksha says. “At that time, we didn’t know they were from the Soviet Union, but their format and design made them irresistible.” The group has even collaborated with an Indian publisher, Lokvangmaya Griha, to reprint five Soviet-era books.

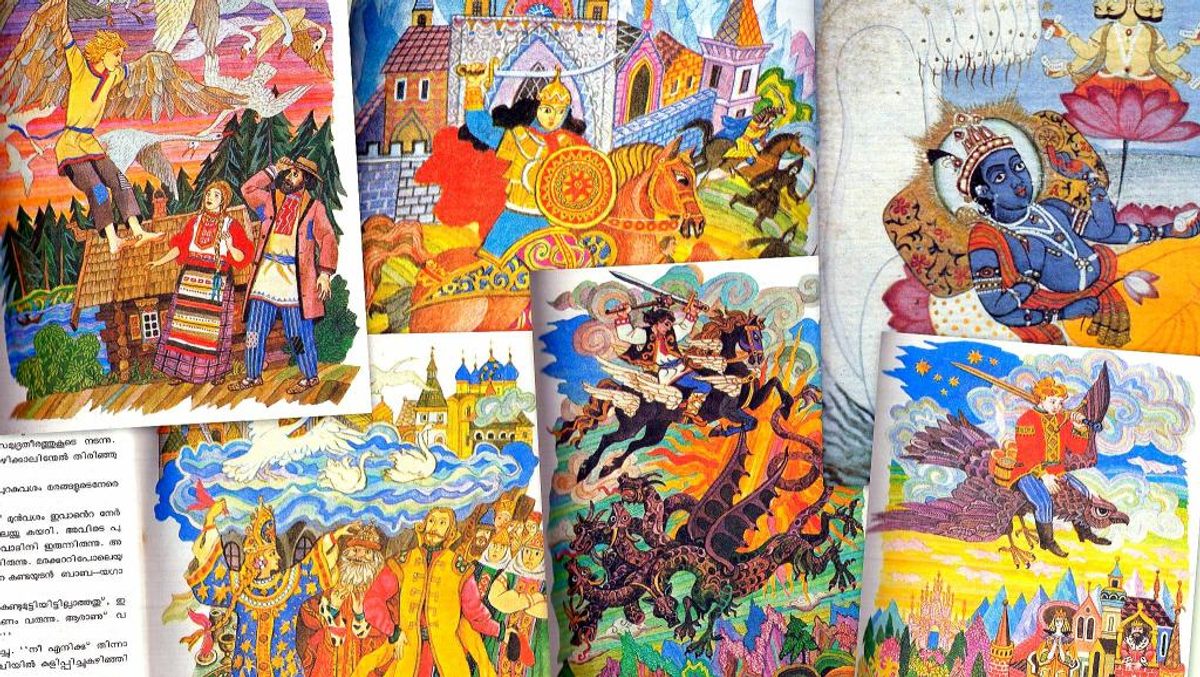

For Indians who grew up in the late 1970s, 80s, and 90s, love of Soviet-era literature is a binding force. Translated books from the Soviet Union were readily available and extremely affordable via book fairs and exhibitions staged by local distributors and book houses in small towns and bigger cities. Across the country, local publishers such as Navakarnataka distributed Indian-language versions of everything from Russian classics by the likes of Gorky, Chekov, Tolstoy, and Pushkin to books on philosophy and popular science, as well as textbooks covering mathematics, physics, chemistry, and engineering. Kids met the elderly Baba Yaga and various other characters in vividly illustrated children’s stories.

The books had a wide reach, but precise publication numbers are hard to pin down. One estimate comes from America’s Central Intelligence Agency, which watched Soviet activities in India closely throughout the Cold War era. Soviet publishers and partner distributors fanned out roughly 25 million books, magazines, and pamphlets in India annually, including some materials published in 13 languages, notes a 1985 CIA intelligence assessment.

Publishers including Progress Publishing House (PPH), Mir, Raduga, and smaller outlets hired Indians to live in Moscow and translate Russian works. One of them, Ravindra Rasal, translated books into Marathi. Rasal, who still lives in Moscow, earned a PhD in Russian language from Moscow State University and joined Mir in 1983. He worked with both Mir and PPH until the USSR broke up in 1991. Unlike PPH, which first translated a Soviet book into English before arriving at the Indian-language version, Mir translated scientific and science fiction books into Indian languages directly from Russian, so that the meaning wasn’t warped in translation. “The quality of our translated versions was very high,” Rasal says.

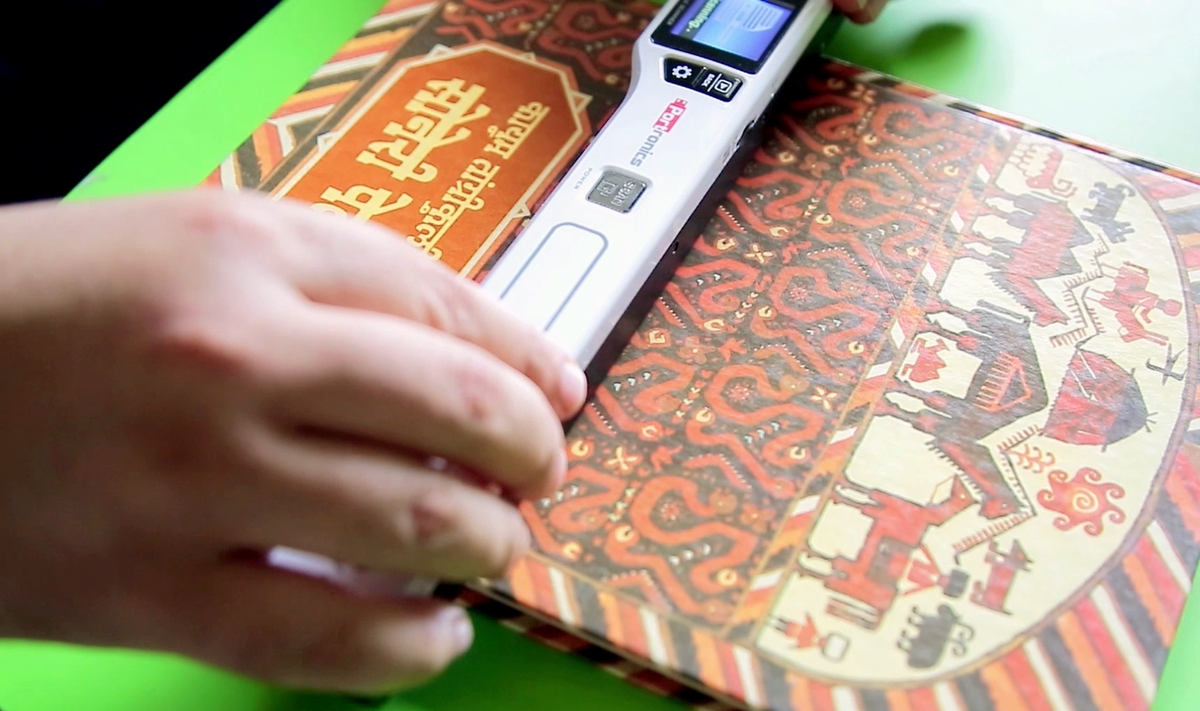

Today, online communities such as the one Rajadhyaksha is a part of are working to create digital archives of Soviet books in languages such as Malayalam, Marathi, Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, Urdu, and English. One of the earliest collections is on a blog by a blogger known only as Da Mitr or The Mitr, which means “friend” in Hindi. An Indian physicist and mathematics teacher, the blogger has been collecting Soviet books for over 25 years. “My collection began from reading All About the Telescope (a book on astronomy by Pavel Klushantsev) when I was about eight or nine,” he says. His collection now numbers some 800 Soviet-era books, many of which have been scanned, digitized, and uploaded to The Internet Archive.

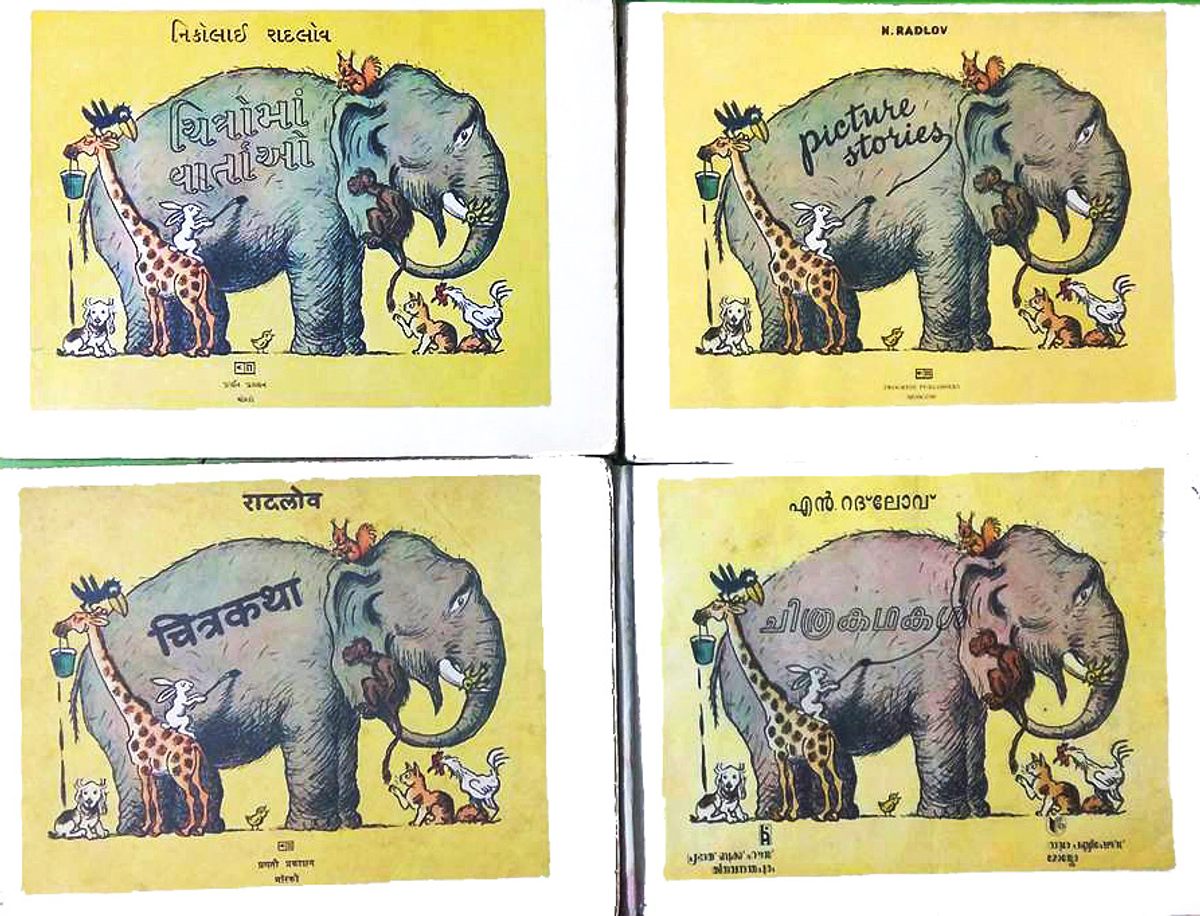

There are several other online communities, most of which launched between 2010 and 2013. All are passion projects, run by book lovers who devote their free time to seeking out Soviet-era books. For instance, Somnath Dasgupta, a chemical engineer in West Bengal, is the heart and soul behind a site and Facebook page devoted to digitizing Soviet books translated into Bengali. In Kerala, a Facebook group set up by Sajid Latheef (a college lecturer teaching English who also writes Gothic horror stories under his pen name, Maria Rose) focuses on Russian books in Malayalam. These groups often preserve the same stories translated into several languages. Alexander Raskin’s much-loved book When Daddy Was A Little Boy, for instance, is Baba Jakhon Chhoto in Bengali, and Achchante Baalyam in Malayalam.

In its 1985 report, the CIA contended that book publishing was a way for Russia to build “influence capabilities” in India and run a propaganda campaign. But Jessica Bachman, a historian at the University of Washington who studies Indo-Soviet cultural and literary interactions from the 1950s to the 90s, says the publishing efforts weren’t exclusively about spreading sentiment. “The exchange did come out of political and ideological motivations, but there were other overlapping motivations as well, such as trade,” Bachman says. “A small percentage of the books did contain anti-American, anti-capitalist propaganda, but the numbers of children’s books, engineering and science books, popular science, and Russian classics far outpaced the propaganda publications.” Moreover, Soviet books introduced Indian readers to unfamiliar layouts, including offset printing, where text and images shared a page. And after Indian independence, a paper shortage meant that books were incredibly expensive. “The Soviet Union stepped in with affordable reading material,” Bachman adds.

Many readers felt personal attachments to the translations. Deepa Bhasthi saw Soviet books and magazines as a child’s way of communicating with other cultures and people. It was a two-way conversation: The children’s magazine Misha, from Pravda publishing, included a pen pal section where young readers could provide their addresses and swap letters with children in the USSR. Bhasthi had two Russian pen pals and discovered that one of them loved Bollywood movies—which, as an episode of 99% Invisible explains, offered a respite from the resolute realism of Soviet art at the time. Bhasthi is now a writer, and believes the books shaped her career path.

This connection to Soviet culture meant that some readers were quite shaken up by the collapse of the USSR. Sreejith Nair, who was 10 at the time, felt devastated. “Tears rolled down my cheeks,” he recalls. “I felt my whole world was coming to an end.” The USSR had seemed like a comforting, protective presence. “I loved the Malayalam-language Russian-origin children’s books I read. Every month, I’d wait for the post to get my copy of Misha and be transported to wondrous faraway lands where fish could talk, frogs could tell tales, and horses jumped over fort walls with gallant princes riding them,” he says. That stopped after the USSR broke up. Driven by those memories, the grown-up Nair now collects Soviet-era books and textbooks.

Soviet-era scientific literature, such as books on engineering, math, and more, also enjoys cult status in India. These volumes are prized by students attempting the notoriously difficult engineering entrance exams for the Indian Institutes of Technology.

Local publishers have occasionally reprinted translations of Russian classics and children’s books, but the quality often pales in comparison with the original editions. Progress Publishers in Moscow has made many books copyright-free, and can connect readers with public-domain editions. That’s good news for readers trying to reconnect with the simpler days of their childhood, when they could journey around the world within the pages of a book.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook