Space Art Propelled Scientific Exploration of the Cosmos—But Its Star is Fading Fast

The huge, hidden cost to severing the bond between art and science.

In a serpentine building that snakes through the Connecticut countryside, a strange meeting took place this past July. A group of four scientists from NASA, including an astronaut, a robotics expert, and the agency’s deputy administrator, conferred with some 30 painters, sculptors and poets. Adding an extra layer of mystery to proceedings was the fact that the meeting was hosted by Grace Farms, a faith-based think-tank co-created by an evangelical hedge-fund billionaire.

Tea was served. Thomas Pynchon may or may not have been present.

The aim of this odd confluence was to engage an “artistic response” to NASA’s journey to Mars, the space agency’s ambitious goal of putting a human on the red planet’s surface sometime in the 2030s. To help set the mood, NASA brought some zappy toys to share—a Hololens headset that offered an augmented reality view of Mars, as well as surreal images of winds carving the Martian surface. According to those present, scientists spoke of the necessity of having “an outpost” on Mars to help solve the many riddles of the galaxy. The question they were asking the assembled artists was whether they could help communicate this vision to the public as part of a new program entitled “Arts + Mars”.

Some of the artists were left scratching their heads. Many of them, schooled in the ambiguities and anti-authoritarian verities of contemporary art, saw NASA’s open call for guileless propaganda as being entirely at odds with the art they practice. “The conversation about art was at such a naïve level,” said one attendee, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of rousing the space agency’s ire. “It just didn’t seem like NASA was that interested in what we had to say.” What’s more the overtly commercial and exploitative language of the Mars boosters—their mentions of partnerships with private industry and “putting tracks on Mars”—did not play well with their youngish, liberal audience.

Concept image of a moon landing from 1959. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

There is no doubt that NASA needs some help. The moon landing will celebrate its 50th anniversary soon and the number of people inspired by actual memories of that event is dwindling fast. With no “space race” to offer a geo-political impetus to the expedition NASA desperately needs to engage the millennial generation in their Martian quest for the next 15 years.

Yet when the NASA scientists asked the attendant artists to refrain from posting pictures of the meeting on social media, it seemed to sum up both a generational and a temperamental mismatch. (In an email, a NASA spokesperson said that ”participating artists are free to discuss their attendance.”)

From a NASA perspective, the secrecy was a budgetary imperative. In 2003, the renowned performance artist Laurie Anderson was appointed NASA’s first “artist-in-residence” with the remit of creating art about the agency’s exploration of space. Republican congressmen quickly seized on the move as a sign of wanton profligacy. “Mr. Chairman,” sputtered Representative Chris Chocola of Indiana on the floor of Congress, “nowhere in NASA’s mission does it say anything about advancing fine arts or hiring a performance artist.” There has been no artist-in-residence since and the reverberations were no doubt part of the reason why NASA’s workshop at Grace Farms seemed tentative and vague.

In the not-so-distant past, though, space and art intermingled happily. Artists were crucial to NASA’s development, at times outpacing the science of space travel itself. What happened?

From the 1875 book Elements of Astronomy. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

When Art and Science Were Friends

In 1542, the German botanist, Leonhart Fuchs, created a book replete with hundreds of extremely detailed drawings of plants. This was unusual. A pervasive prejudice dating back to antiquity had scorned the usefulness of visual images in scholarship. Writing in his introduction, Fuchs railed against such lunacy: “Who in his right mind would condemn pictures which can communicate information much more clearly than the words of even the most eloquent men?”

From the Renaissance onwards, art and science became inextricably bound together. You can see it in Leonardo Da Vinci’s sketchbooks that he used as laboratories for his thinking, and you can find it 300 years later in John James Audubon’s lushly illustrated catalogue of American birds.

However sometime in the 19th century the introduction of photography and its offspring—cinema, radiography—severed this relationship. Scientists embraced these new technologies for their clarity and dispassionate precision. Artists, meanwhile, felt liberated from having to reproduce the natural world realistically, and began infusing it with their own subjective emotions. Once bosom buddies, art and science slowly drifted apart from each other, without either seeming to mind too much. Science still needed some illustrations, but illustrations now seemed more handmaidens to science than the equal partner they had once been. It’s notable that the greatest of anatomical textbooks, Gray’s Anatomy, published in 1858, is named after its author, Henry Gray, and not its illustrator, Henry Vandyke Carter.

Nevertheless there were still some areas of science that photography could not touch. Chief among them was outer space, which was too far away to be photographed yet too thrilling to be left undocumented.

These subjects required imaginative as well as illustrative skills to help understand them. The space artist was born.

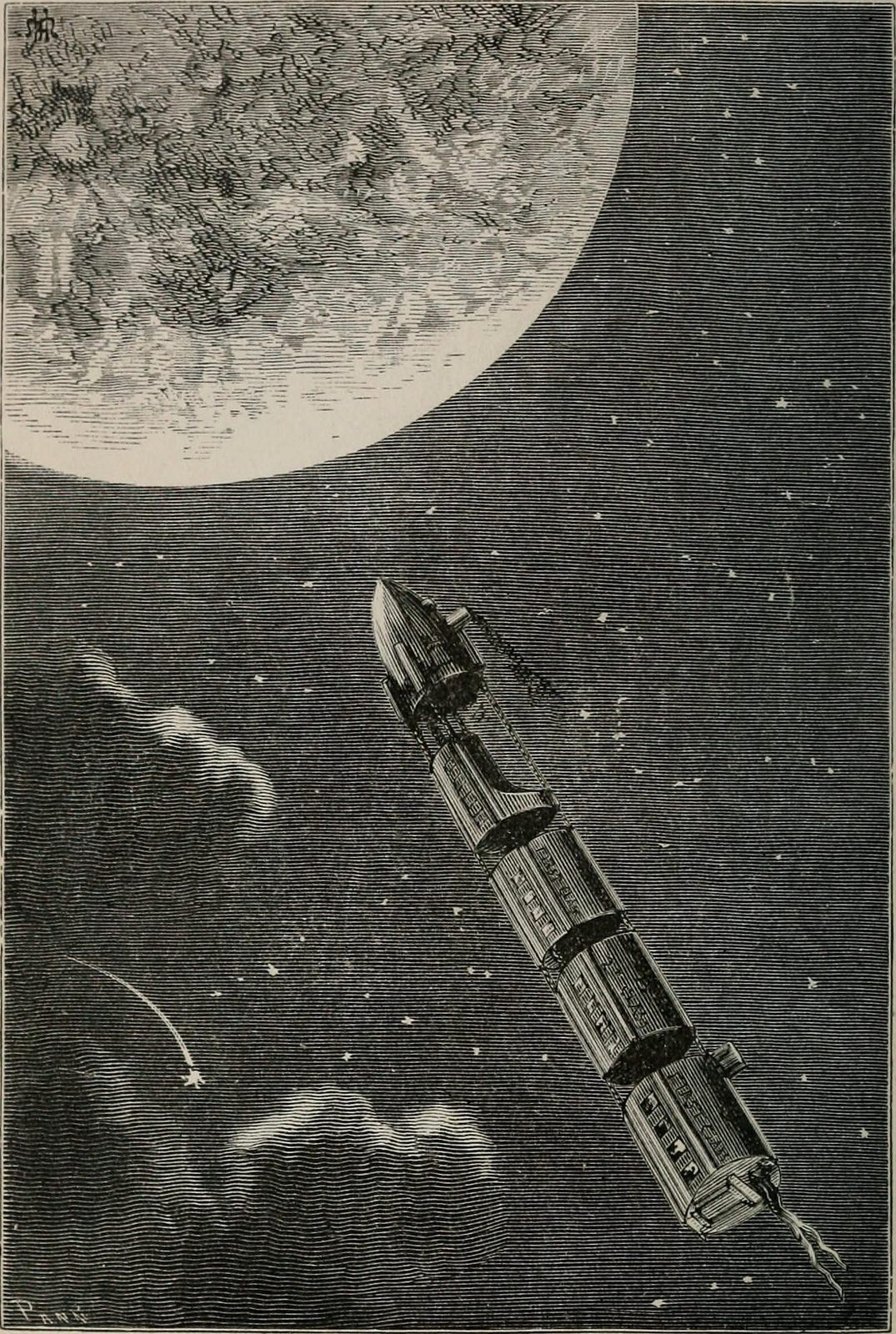

An illustration from the frontispiece to From the Earth to the Moon. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

How Space Art Took Off

Space art can trace its beginnings to the illustrations found in Jules Verne’s 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon. Before Verne, tales of outer space had largely been venues for satire, mysticism and comedy. But Verne chose to portray space travel realistically using the scientific data that was available to him at the time, and his illustrators followed suit.

Sometimes, the illustrators surpassed the scientists. In the early 20th century, Lucien Rudaux, a French commercial illustrator and amateur astronomer, created countless pictures of the moon taken from his own observations. Rudaux was baffled why scientists spoke of the moon as being dominated by towering jagged peaks. He believed it should be depicted with smoother more rounded terrain, a fact that would only be verified with the Apollo moon landings more than 20 years after his death.

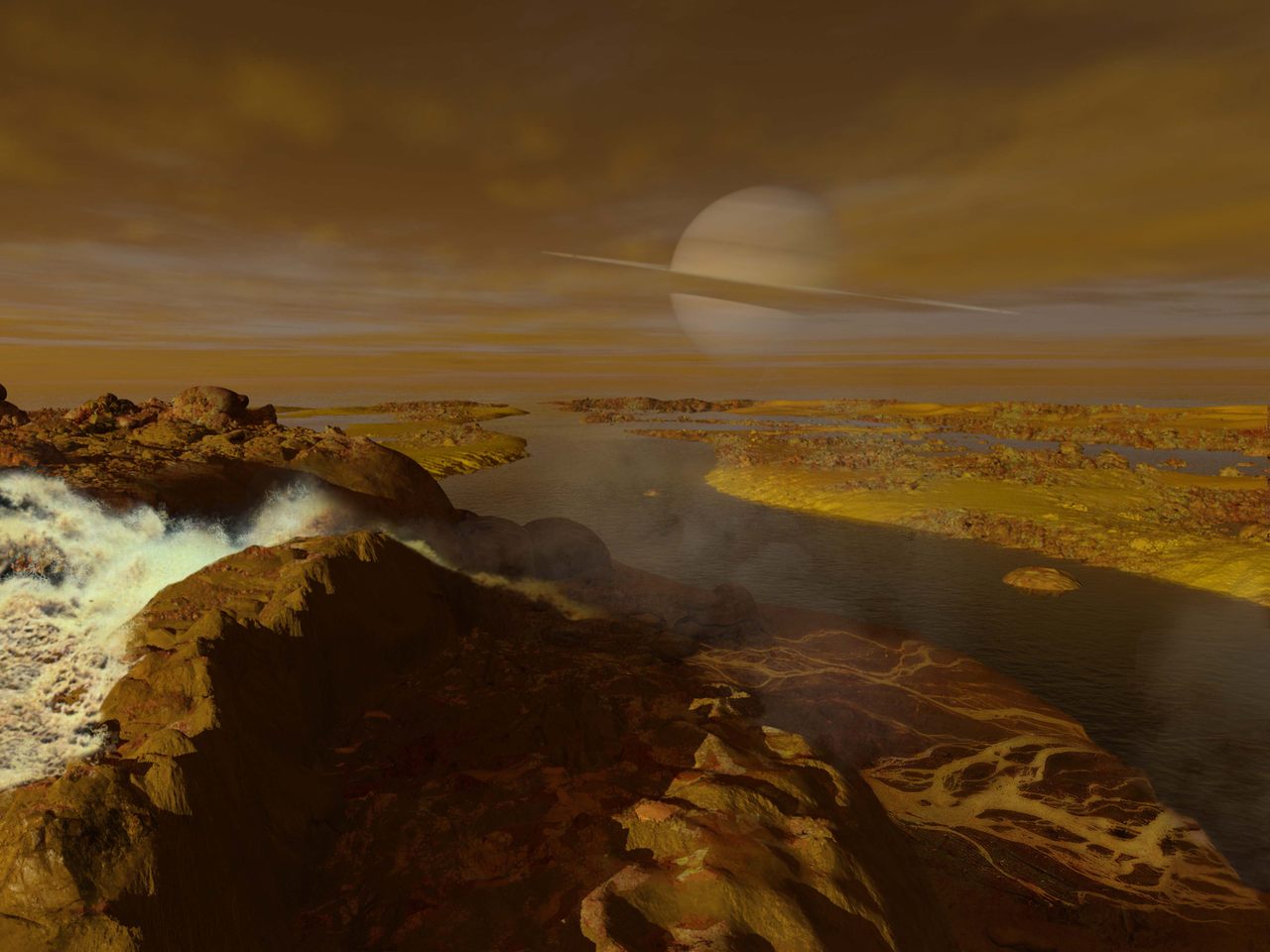

However the discipline took its greatest leap forward with the work of one specific pioneering American space artist. Chesley Bonestell had trained as an architect and worked as a designer on the Chrysler Building in New York—perhaps an inspiration for his subsequent pictures of space rockets. But it was a series of paintings he created for Life magazine in 1944 that caught the imagination of a war-weary public searching for transcendence. These paintings showed Saturn from the perspective of its moons, an impossible view but painted in a realistic and plausible manner. His depictions of space travel were so vivid that he almost single-handedly rid it of its Buck Rogers connotations, stirring up a torrent of public and government interest and support.

Chesley Bonestell’s Saturn as seen from Mimas, 1944. (Photo: Reproduced courtesy of Bonestell LLC)

“Most scientists simply don’t think visually,” says Ron Miller, one of the most well-known and prolific space artists working today. It is this ambivalence towards the visual that he sees as lying at the heart of the continued split between the two disciplines. Miller knows a thing or two about getting people excited about space. He has created space-themed postage stamps, been a production designer on David Lynch’s Dune, and painted countless otherworldly scenes for books and magazines. He believes it is the space artist’s remit not only to reveal science’s discoveries to the world but also to build enthusiasm for it, to be the educator that NASA seems to be looking for in its Arts + Mars program.

For Miller, the true precursors to the space art of today were the painters of the Hudson River School. “Back in the late 19th century when Yosemite and Yellowstone [national parks] were discovered, artists like Thomas Moran and Alfred Bierstadt painted gigantic paintings, 10 feet, 20 feet wide, that actually toured the country,” he says. Indeed if you look at Moran’s painting of Castle Geyser in Yellowstone, the image is strangely alien, the landscape singed, the lake an ungodly blue, the sky dashed grey-black as if it had been scorched by fire.

“Their purpose was to make people believe that these insane places existed,” he says.

Thomas Moran’s painting of Castle Geyser from 1874. (Photo: Boston Public Library/Public Domain)

Jon Ramer, President of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA), concurs. “We seek to inspire people to want to go and see what is ‘out there’ in our universe,” he says.

It’s strange to think that while space exploration is a defining factor of the modern era, many space artists hearken back to the landscape painting of a pre-modern age to depict it. Largely this is due to space art still following Leonhart Fuchs’s dictum of communicating information clearly. But perhaps this is also a nostalgic wish to return to a time when scientists and artists took each other’s work seriously.

When Chesley Bonestell was painting his realistic planetscapes in the late 1940s, Wernher von Braun, America’s leading rocket scientist at the time, called his art “the most accurate portrayal of those faraway heavenly bodies that modern science can offer.” This was an astonishing pronouncement. It suggested that Bonestell’s imaginative renderings were as important as von Brauns’ own calculations. Certainly Bonestell felt that his art was as rigorous as the science he depicted. When von Braun sent him some sketches of possible rocket ship designs they were returned with blistering criticism of the scientist’s inconsistencies and oversights.

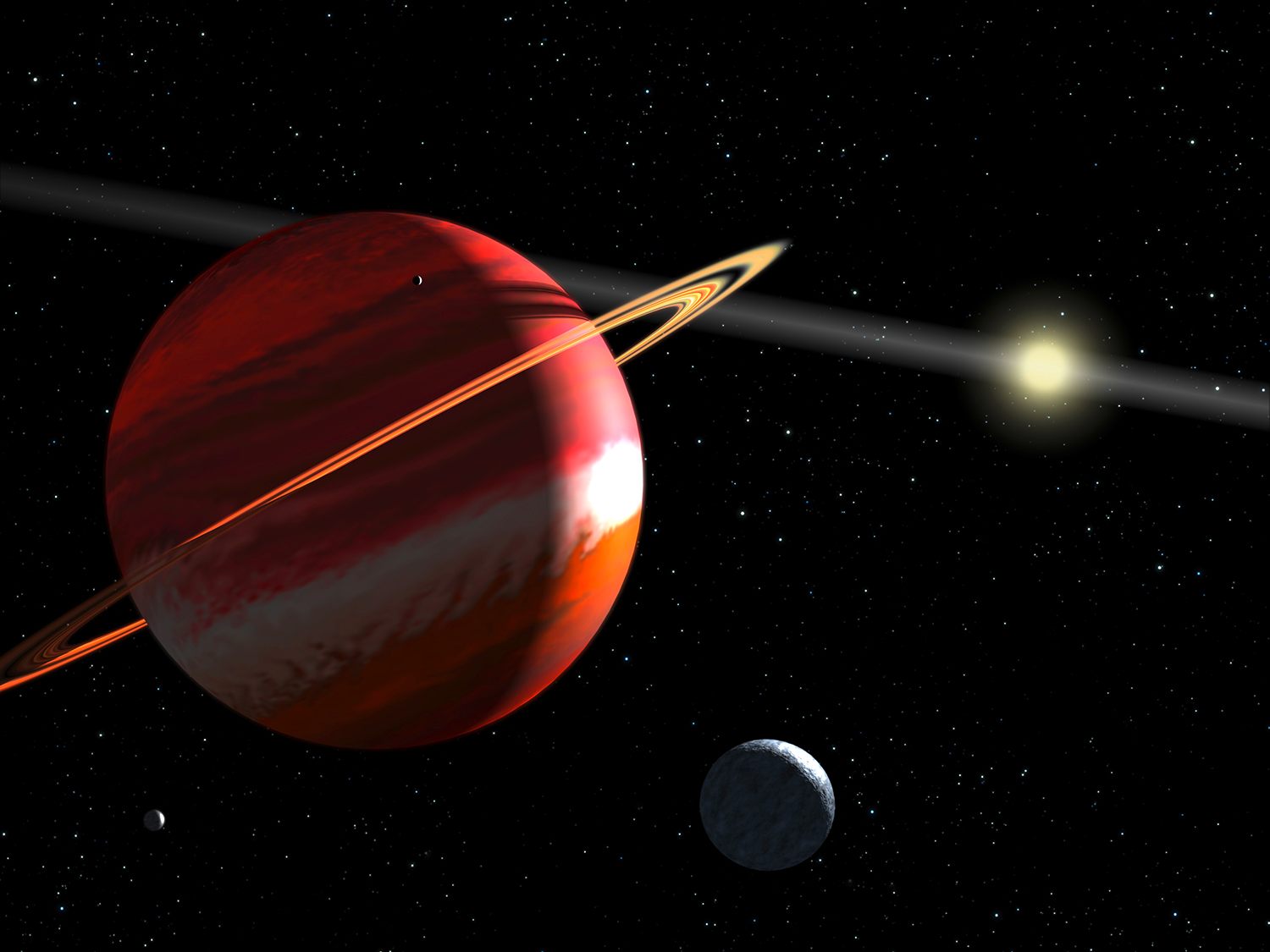

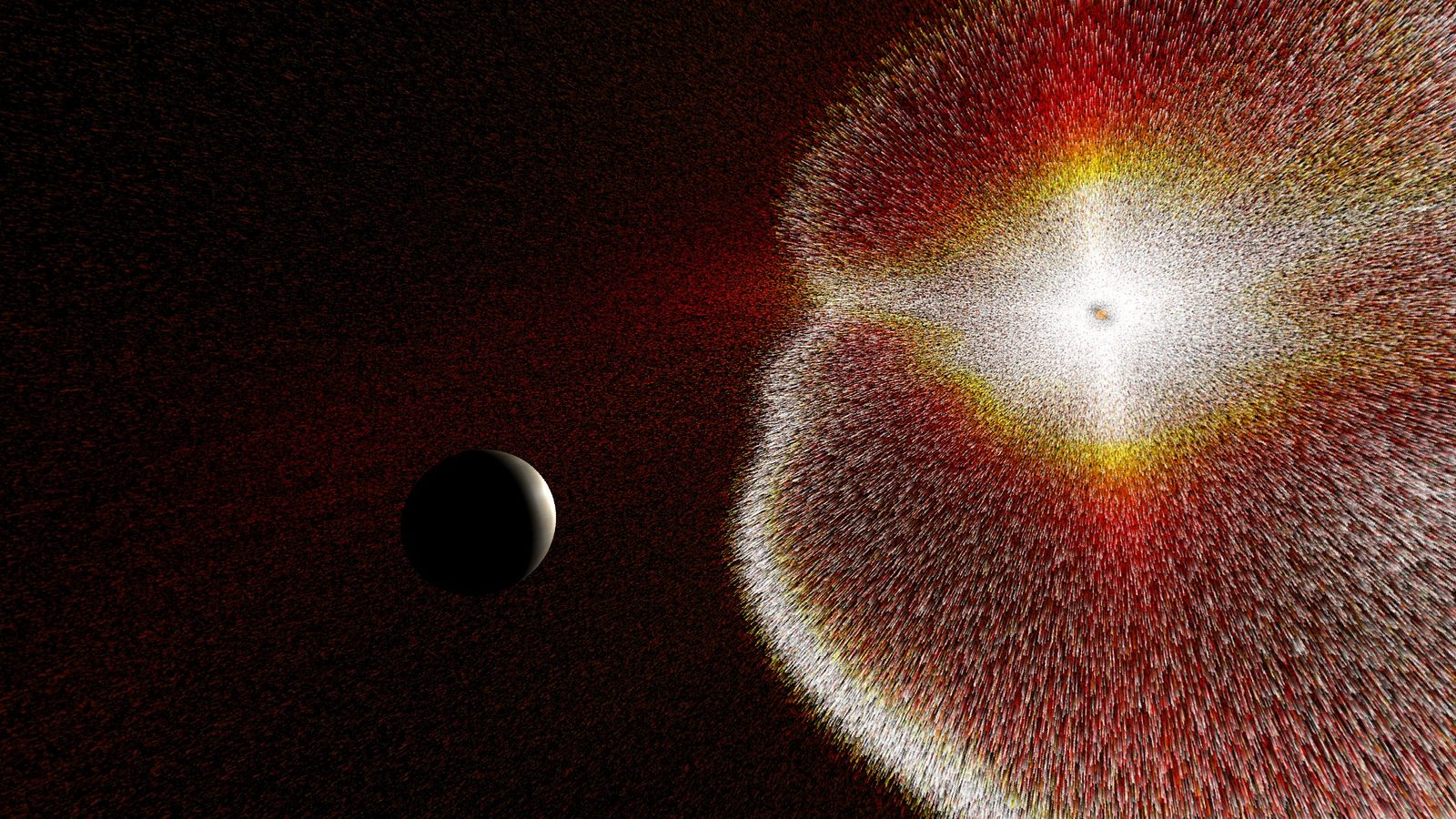

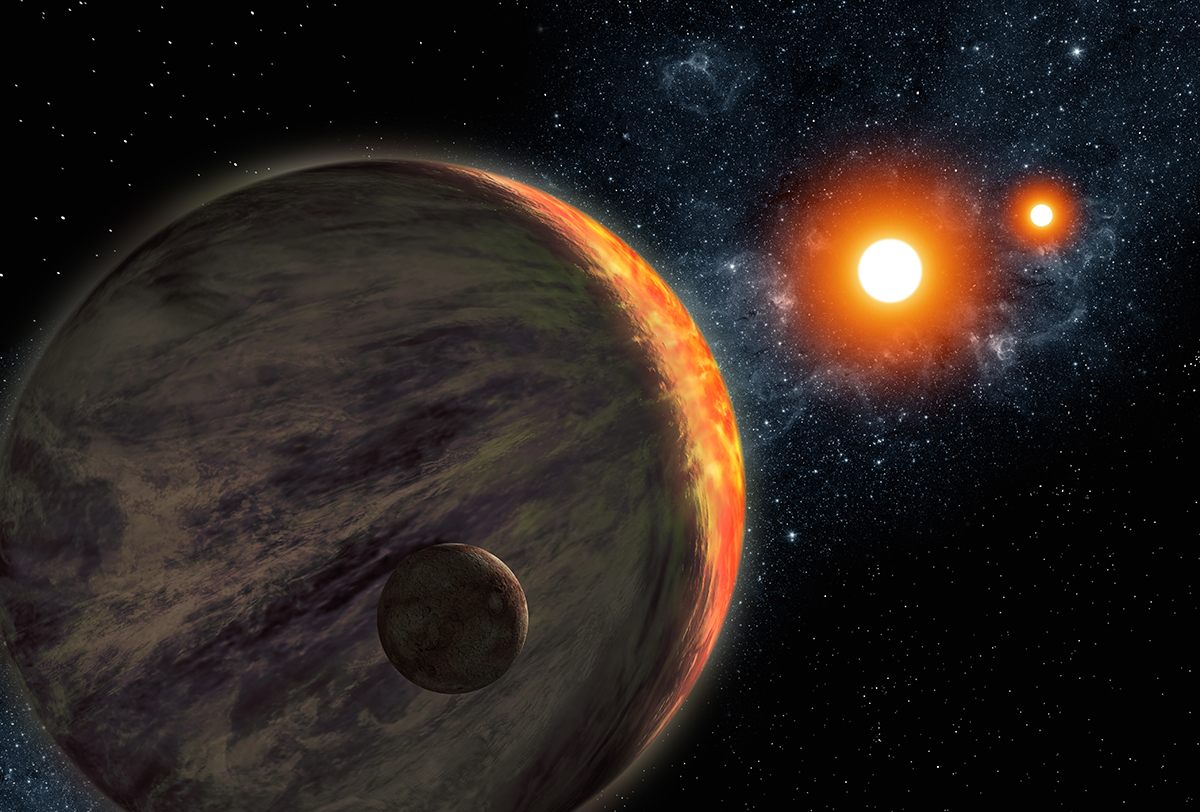

From the European Space Agency, an artist’s concept of the nearest exoplanet to our solar system. (Photo: NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI))

Enter the Exoplanet

The year was 1995 and something was making a distant star called 51 Pegasi wobble. It wasn’t wobbling much but it was wobbling enough that there were small fluctuations in the light it emitted. These small changes had been picked up by an earthbound spectrometer, a machine that analyzes the shifting spectrum of starlight, and scientists at the Geneva Observatory were now puzzling over the numbers. They eventually came to the conclusion that the only thing that could cause a star to wobble in such a manner was a planet, for just as a star’s gravity affects the movement of planets, so a planet’s gravity affects the movement of a star.

Space aficionados reacted immediately. Although scientists and science fiction writers had for centuries imagined countless planets in other solar systems, scientists had never before actually found proof of a single one.

There was just one problem: Although 51 Pegasi b’s existence as an exoplanet orbiting a sun like our own could be inferred, it couldn’t actually be seen. 51 Pegasi b lies approximately 300 trillion miles away from Earth and gives off a feeble amount of light compared to its star. So although this discovery was hailed as one of the greatest of our age, something felt like it was missing—namely, visual evidence.

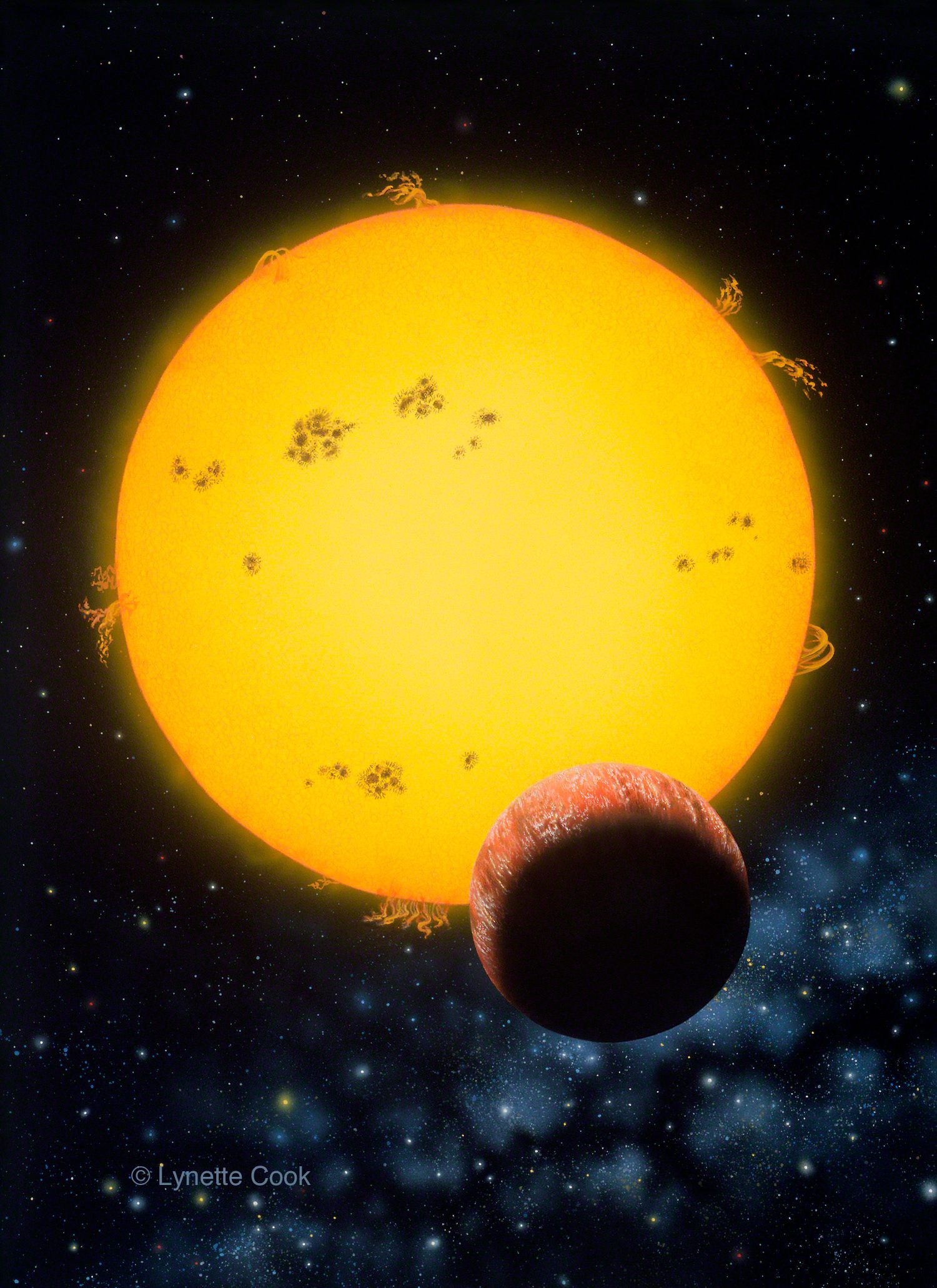

At the time of this discovery Lynette Cook was a freelance scientific illustrator living in San Francisco. She was working part-time as an artist and photographer at the Morrison Planetarium at the California Academy of Sciences, providing visuals of our cosmos to the delight of children, adults and stoned teenagers. When a scientist friend suggested she try her hand at depicting this new discovery she thought, “Why not?”

Working for free, she first discussed 51 Pegasi b with various astronomers and tried to pin down its size, color, distance to its star and possible composition. Then she turned to her paints. The result, created in a mixed media combination of gouache and colored pencil, was the first ever picture of a confirmed exoplanet. Cook depicted it alongside its churning sunspot-specked star, the superheated gases in its atmosphere giving it a red luster as clouds of iron vapor streaked across its surface. From a barely-detectable inference, 51 Pegasi b was finally revealed in all its terrible glory.

Lynette Cook’s artwork of 51 Pegasi b. (Photo: Lynette Cook)

Although astronomers initially seemed uninterested in Cook’s work, the media was hungry for images. Cook’s artwork was thus used countless times in documentaries, magazines and books. Indeed the painting of 51 Pegasi b proved pivotal to her career and was the first of many exoplanets she portrayed. The original was eventually purchased by the Geneva Observatory where it hangs as the sole physical embodiment of a remarkable discovery.

Work like this, says Bill Hartmann, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, can do more than just get people excited about space travel; it can help improve the very science it depicts. Hartmann was an investigator for the Mariner 9 probe that mapped Mars for the first time in 1972. He originated the now-accepted theory that the moon was formed by the earth’s impact with another planet some 4.5 billion years ago.

He’s a visionary thinker. He’s also a space artist.

Hartmann sees his artistic role as being that of a synthesizer, blending a mass of disparate and highly specialized astronomical data into a more complete whole. This is often necessary in a field that wallows in minutiae at the expense of the big picture. Hartmann remembers attending a scientific conference where the brightness of the auroral glow around one of Jupiter’s moons was announced in kilo-rayleighs (a unit of measurement). When Hartmann asked if that meant it could be seen by the naked eye the scientists giving the presentation were dumbfounded and couldn’t come up with an answer. “This question hadn’t occurred to them as something interesting to know,” he says.

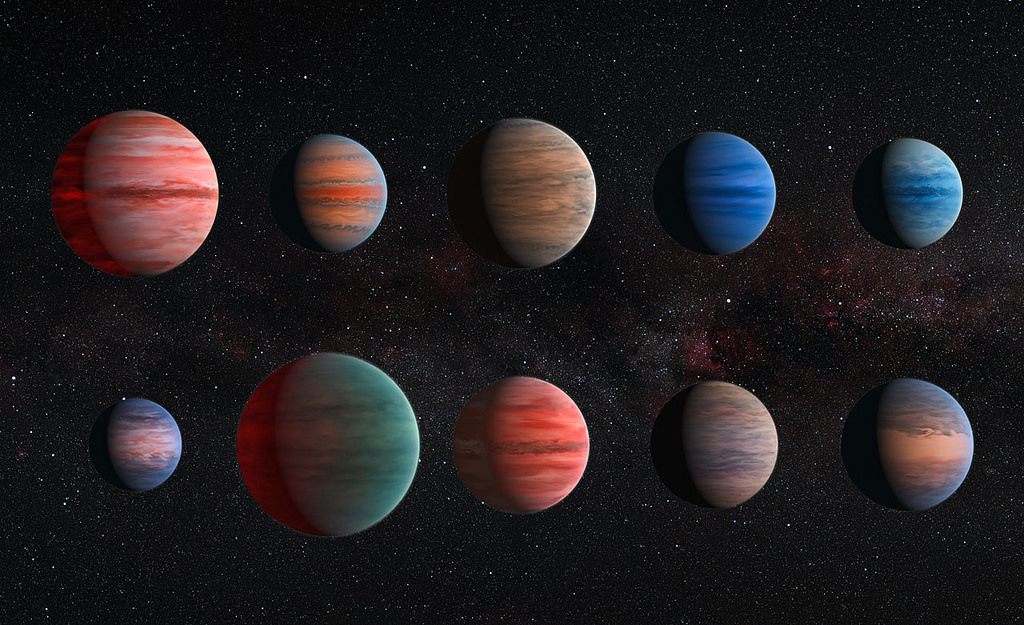

An artist’s impression of 10 hot Jupiter exoplanets, drawn to scale with each other. (Photo: ESA/Hubble & NASA/CC BY 2.0)

He explains how in the 1970s there was little overlap between the scientists who studied icy comets and those who studied rocky asteroids. When Hartmann decided he wanted to paint a comet as if he was standing on its surface he realized that there was “essentially no work” on the comet’s possible geology. Only asteroid structures had been studied but surely, he thought, the two must have features in common. Hartmann’s painting thus led to the sharing of ideas between two previously unconnected fields of research. “Art has long been used to clarify science, and vice versa,” he says. “Leonardo Da Vinci sketched waves to learn about wave motion but dissected bodies so he could paint better portraits.”

Since 51 Pegasi b first swam into view 20 years ago, over 3,000 other exoplanets have been discovered. They vary in size, density and absurdity with some planets believed to have atmospheres of vaporized rock and mantles of liquid diamond. As such you’d think these would be boom times for space artists like Lynette Cook but in fact it’s been quite the opposite. Her space art career has never been more tenuous.

“The budgets to hire people like me on the part of publishers and science organizations has really dwindled in recent years,” she says. Partly this is due to recent changes in print economics. Cook has watched as publishers have become increasingly willing to use inaccurate and poorly rendered “no-fee” illustrations to keep costs down. “I saw a shift,” says Cook, “from commissioning new art, to wanting me to rework earlier images, so they looked different (but didn’t cost as much), to reusing older art “as is” for new discoveries.” Eventually her clients simply stopped calling, “as if they were stars in the heavens that were winking out.”

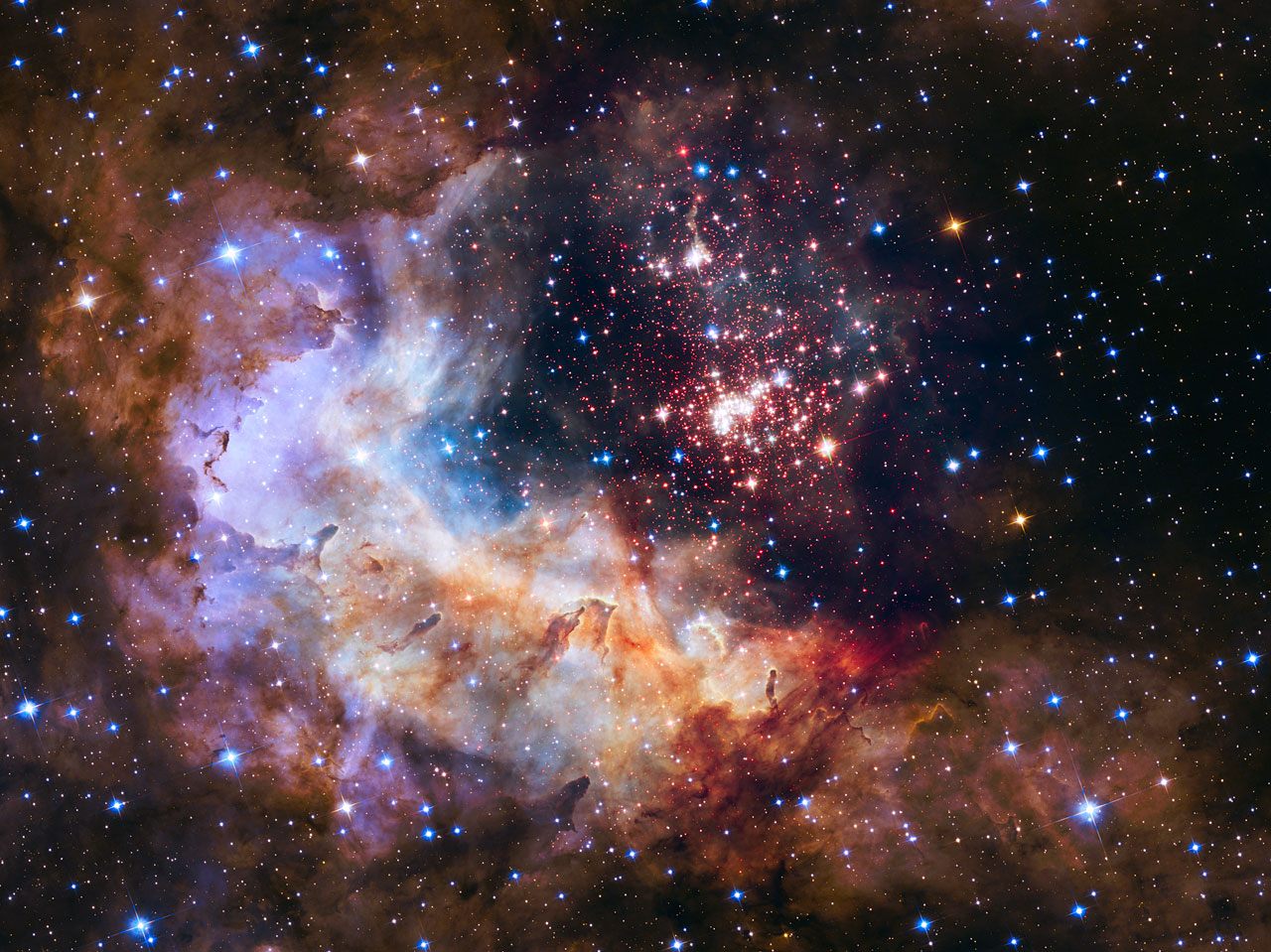

An image from the Hubble Space Telescope of Westerlund 2, a star cluster. Space photography has also impacted space artists. (Photo: NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), A. Nota (ESA/STScI), and the Westerlund 2 Science Team)

There is another slayer of space art budgets, though: the success of space photography. Over the past two decades huge amounts of photographic imagery has been sent back from NASA probes at Pluto, Ceres, and Saturn, not to mention the Hubble Telescope. These images were primarily intended for scientific research, but the fact that they were beautiful—and rights-free—hasn’t hurt in raising public awareness in NASA’s mission. The only people it has hurt are the space artists.

Outer space is getting easier and easier to see. The camera’s reach has gotten ever longer and, as the depths of the universe have become increasingly familiar to us, there appears to be less demand for the imaginative types of space art as practiced by Chesley Bonestell, that less than a century ago inspired us to strap a man to a rocket and blast him off our planet. For all the ostensible benefits of art and science working together, artists have found themselves being squeezed out of the field of astronomy, just as they had out of the life sciences in the 19th century.

Solarium concept art at NASA. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/ Public Domain)

Eye Candy Goes High-Tech

In the hyperwall room at NASA’s Goddard Research Center in Maryland it is hard not to feel like God. There in front of you is the Earth portrayed in super high definition on a huge wall of video monitors. The forces and emanations that shape it ebb and flow before you—whirling ocean currents, roiling clouds of carbon dioxide, and the madly pirouetting paths of hurricanes. You can focus on a particular region or just let the whole thing wash over you as if you were in an ambient chill-out room, albeit one filled with sober men wearing laminated tags.

These animations are the work of the Scientific Visualization Studio (SVS) whose job it is to turn the myriad sets of data NASA scientists produce into images that explain, entice and entrance. Using software created by the animation studio Pixar, Dr. Horace Mitchell and his team of 10 visualizers make science palatable to both the public and the grant-endowing poobahs of NASA who, overseeing such a vast and diverse enterprise, are just as likely as the public to need some scientific hand-holding.

“In the early days I think the scientists were more focused on getting their work done, getting the next paper out, getting their reputation established. They looked at this as eye-candy,” Mitchell chuckles. Climate change, Neil deGrasse Tyson and the evolution of social media have shifted this landscape. “Now I think there are very few scientists who don’t understand the value of public outreach.”

A still from the video Dynamic Earth: Exploring Earth’s Climate Engine, created by NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/CC BY 2.0)

The animations SVS creates are more an alluring extension of graphs and charts than they are a subjective depiction of the world. This is what traditional scientific illustration became. It doesn’t aim to inspire new scientific ideas or help improve a scientist’s work, but it does seek to make the specialized scientific knowledge comprehensible. “Sometimes you have to show people something before they understand its worth,” says Mitchell.

As an educational tool, its purpose is tightly defined—the SVS graphics are more translation than expression. This is art on NASA’s terms, closely clinging to the data. Occasionally, however, translation can become its own form of expression.

Tucked into a cramped corner of NASA’s ramshackle visitor center is the video installation known as Solarium. It depicts the sun’s raging ultraviolet light, normally invisible to the naked eye, but here colorized and cropped. For the viewer pressed up against the images by necessity of the tiny space, the view is all-encompassing—you feel as if you’re flying over a firestorm—and the chance of fully comprehending it is minimal. One looks first, and enquires second. Transforming the data into immersive visceral thrills without heed to its practical purpose seems something of a bold move for NASA, almost a misuse of sacred data, but it suggests that the Art + Mars workshop at Grace Farms this summer might not be as much of a dead end as it seemed. Although Solarium is hidden away like a mad aunt in the attic, it’s a tentative step out of the quantifiable world of data and into one of subjective experience. In doing so it seems to get to the very essence of NASA’s mission statement: seeing the unknown with your own eyes is, after all, the very essence of exploration.

A still from the video for Symmetry, filmed at the Large Hadron Collider. (Photo: Courtesy Arts@CERN)

Dance Like NASA’s Watching

People are dancing in the Large Hadron Collider. Somewhere beneath the French-Swiss border, men in blue hardhats are spinning, falling, leaping, and doing things that particle physicists don’t normally do. They are part of a dance-opera that was unveiled last year called Symmetry, just one in a long line of artistic interventions organized by the European Organization for Nuclear Research’s official arts program, Arts@CERN.

Over the past five years sculptors, photographers, musicians and filmmakers have been invited to CERN (which takes its name from the French moniker Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) to create works inspired by its science and to stimulate the minds of the 10,000 engineers and scientists who work here and at other CERN facilities. Just as the Large Hadron Collider smashes particles into one another to test different theories about the underlying structure of reality, so the arts program seeks to create similar collisions between art and science. Scientists have been surprised in the CERN library by slow-moving dancers crawling under their chairs or by having the sounds of the collider recorded and played back to them. Sound artist Bill Fontana, photographer Andreas Gursky, and the sculptor Anthony Gormley have all had residencies here, each one accompanied by a “scientific partner” drawn from CERN’s staff.

The question is what are they hoping to gain.

Ron Miller’s depiction of Kepler-16b. (Photo: Ron Miller)

“We need to bring other voices inside our conversation,” says Monica Bello, the head of Arts@CERN. “Artists are the most radical thinkers in a non–systematized environment, they are really pushing new questions. They are rigorous in the way they process information and in the way they interact with other experts.” On the one hand, Bello sees the artists transmitting CERN’s extremely complex deeds to a worldwide audience in museums and galleries, but she also sees the arts programs as having the holistic aim of “supporting artists and scientists talking to each other, focusing on developing devices together, thinking how knowledge is expanding and having many other kinds of conversations.” When asked what the main aim of the program is, Bello says simply, “We’re supporting research.” It’s part of Arts@CERN’s success that she doesn’t need to say whose research they’re supporting. Scientist and artist have become one.

A growing movement seems to understand the importance of the visual to science. This is especially true in the more theoretical sciences where, free from the camera’s prying lens, an artist is needed to visualize the concepts. Take, for example, the art of Professor David Berman, an authority in the tortuous complexities of string theory, whose prize-winning collaborations with contemporary artists have thrust theoretical astronomy into the art world and artists into the world of theoretical astronomy. This is space art at its furthest, invisible frontier. Berman’s reasons for doing so are clear: “If you can imagine doing an experiment in which you have a group of scientists who sat isolated in their offices and didn’t talk to artists, or weren’t exposed to art, and then you had scientists who talk to artists and are exposed to art, and then saw what research they produced after x number of years, then I believe that the diverse scientists would do better.”

Yet there’s still some way to go. While other scientific agencies have instituted artistic residencies few are as well-integrated, or as well-funded, as Arts@CERN. CERN’s budget for artistic residencies and art activities ranges between $225,000 and $337,000 a year, and has, so far, not appeared to raise any eyebrows amongst the European nations funding it. It is hoped that the CERN model can inspire other scientific ventures to follow suit.

It’s certainly a model that Lynette Cook, exiled from the very science she helped to popularize, can appreciate. “Anything that brings artists and scientists together to collaborate in some way —and which also provides funding to said artists—is a good thing, in my opinion,” she says. Indeed Arts@CERN often seems to be striving to recreate the Renaissance mindset of art and science being so obviously useful to one another that nobody in their right mind would challenge it. Might NASA’s Arts + Mars program follow this route?

There are hopeful signs. Shortly after its inaugural meeting in July, NASA announced that it would be developing “action steps” for its Arts + Mars program in 2017. It also dropped its stipulation for secrecy from the attendant artists (although it did provide a pre-approved statement for the artists to use on their social media—old bureaucratic habits die hard). In shoring up the relationship between art and science, NASA does more than improve the odds of the popular success of the Mars mission; it takes one giant leap towards getting rid of the pervasive prejudice that art has no role in science, and science no role in art.

Update, 9/22: An earlier version of the story said that Grace Farms was created by an evangelical billionaire; it was a co-creation. We clarified the text.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook