How Russia’s Space Dogs Inspired a Galaxy of Swag

The cutest little cosmonauts launched a zillion tchotchkes.

It is no small feat to become one of the few to travel in space. To stand a chance with NASA, for example, an applicant must have an undergraduate degree in engineering, math, or science, as well as at least three years of related work experience or 1,000 hours behind the controls of a jet aircraft—and nearly perfect vision (or glasses that get it there). In 2016, there were more than 18,300 human applicants vying for precious few seats. In the middle of the 20th century, as the Soviet space program ramped up, the job criteria were different: The missions called for candidates who were easygoing, telegenic, and no more than 13 inches tall. And they all had to be dogs.

Those qualifications were from a time when the American and Soviet space programs weren’t sure that any living thing could handle the journey beyond our atmosphere. So they sent animals up first. Fruit flies, monkeys, mice, dogs, and a chimp all reached space before humans dared to, in order to see whether it was possible to send a living thing off-world and bring it home unscathed. In many cases, it wasn’t. Some creatures were never intended to even attempt the return trip, and others died along the way or upon reentry. When the ethics of this form of animal testing were noted at the time, they were overshadowed by the geopolitical implications of the space race. And that attention made some of those early animal spacefarers into bonafide superstars. Perhaps none shone brighter than Laika, Belka, and Strelka, three dogs sent to space by the Soviet Union.

These pups, and the seemingly endless parade of merchandise that featured their little whiskered faces, are the heart of Space Dogs: The Story of the Celebrated Canine Cosmonauts. The new book pairs text by science journalist Richard Hollingham with photographer Martin Parr’s extensive collection of space-dog swag, collected through two decades of combing eBay and Moscow flea markets.

Beginning in summer 1950, Soviet researchers enlisted potential canine cosmonauts by driving through the Moscow streets and plying strays with little bites of sausage. The most promising recruits were the right size, docile, light-colored, and female—an advantage partly because they wouldn’t feel compelled to lift their legs to pee, which could make a big mess in microgravity. The best among those were housed in a suburban mansion, where they underwent medical exams, plus simulations to mimic the noise, vibrations, and pressure they’d encounter during launch. The first space-mutt duo, Tsygan and Dezik, went for a suborbital flight in a capsule in July 1951 before drifting back to Earth via parachutes. They landed safe and sound, but Dezik died in another mission later that month.

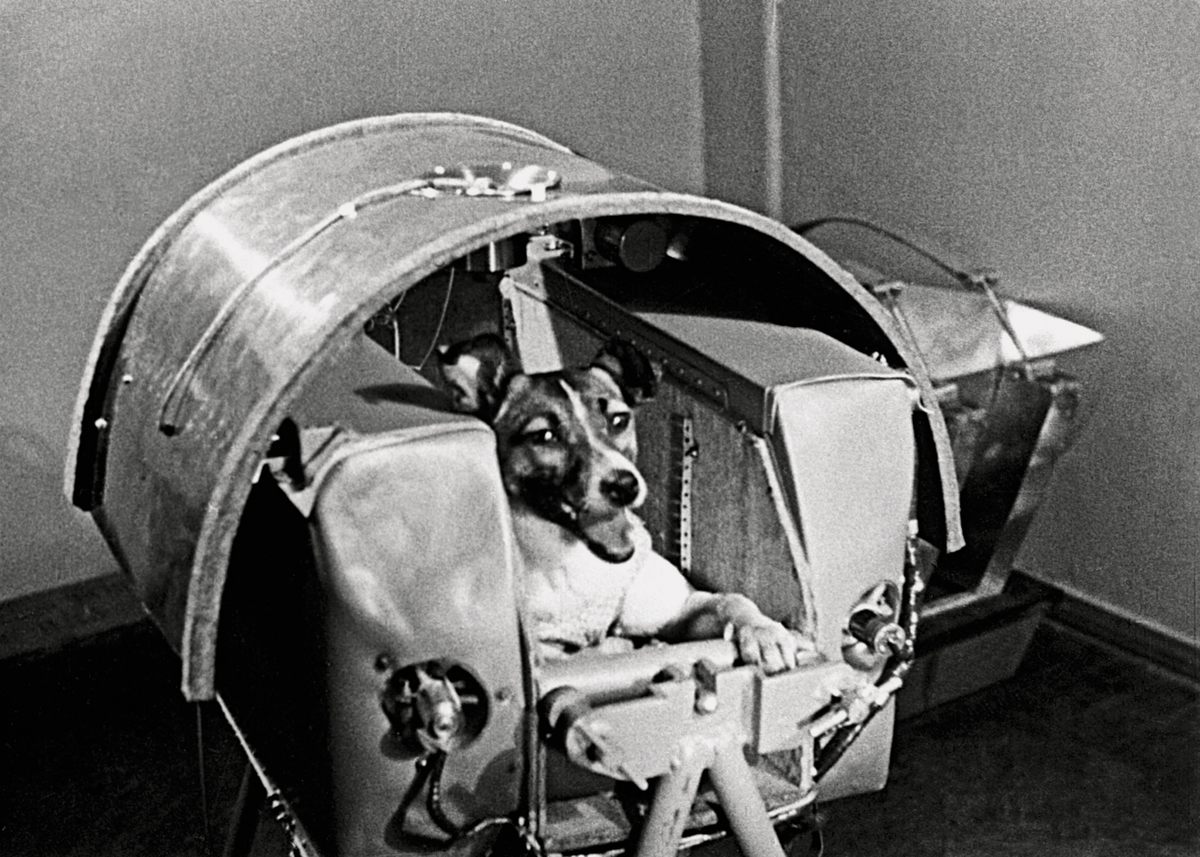

Several other dogs flew on suborbital flights throughout the decade, but Laika—a little pooch who was probably a husky-terrier mix—was the first to go into orbit, on Sputnik 2, and was the first cosmonaut to really fetch public affection. Her narrow face, flanked by golden stars, rockets, planets, and slivers of the moon, popped up on stamps, postcards, porcelain plates, clocks, watches, cigarettes, matches, and much more—anywhere there was room to plaster it. She was often depicted as Lenin was, Hollingham writes—chin slightly lifted, noble gazed fixed out on the horizon. Though the public didn’t know it at the time, Laika’s mission was always going to be one-way; the Soviets didn’t yet possess the technology to pull a spacecraft out of orbit and land it back on Earth. But on these pieces of patriotic propaganda, Hollingham notes, “the dog was presented as though she had known she was dying for an important cause: helping her masters conquer outer space.” Much later, at a press conference in 1998, Soviet scientist Oleg Gazenko expressed doubts about having dispatched Laika on a death mission. “The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it,” he said.

Though she died within hours of being in orbit, probably from overheating, Laika proved that living creatures could withstand leaving the atmosphere and being in microgravity. In 1960, a duo named Belka and Strelka orbited the Earth 18 times and returned safely home, tails awag.

When their paws hit the ground, the business of space-dog swag truly boomed. “Laika souvenirs had been popular,” Hollingham writes, “but Belka and Strelka took the commemorative space dog business to a whole new level.” The pair appeared on wall clocks, collectible coins, nesting dolls, porcelain decanters—including one shaped like a rocket, with their little heads poking out of portholes, as though they were riding in a car, ears flapping in the breeze.

In a diplomatic power move, Nikita Khrushchev later sent the Kennedy family one of Strelka’s puppies, a dog named Pushinka (Пушинка), or Fluffy. She hit it off with Charlie, one of the Kennedy family dogs, and soon the White House had an international litter on their hands. More than 5,000 kids wrote in asking for one, and the “Red Space Dog’s grandpups,” named Streaker and Butterfly, eventually went to a Missouri boy and a girl from Illinois, the Associated Press reported. It’s hard to imagine a cuter space-dog souvenir.

The last of the Soviet space dogs flew in February 1966, when Ugolek and Veterok spent several weeks in a windowless craft, while implanted heart monitors tracked the effects of longer spaceflight on their bodies. Ultimately, Hollingham writes, “the dogs helped enable the Soviets to establish space stations and, with the results of the experiment published around the world, added to NASA confidence in sending astronauts through the Van Allen [radiation] belts and to the Moon.” Though the era of the space dogs has ended, they haven’t been forgotten. A monument to Laika went up in Moscow in 2008, and Belka’s taxidermied remains can be seen at the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics. Meanwhile, handpainted decanters and little porcelain versions of Belka and Strelka are available from the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles.

In the several decades that people, plants, and pets have been orbiting our planet, landing on the Moon, or docking on space stations, one thing remains clear: Space is not an easy place to stay alive. Up there, fluids float freely, which means that human faces wind up swollen, with plugged sinuses, and plants are often either waterlogged or parched. Muscles and bones weaken from disuse, and without the buffer of our planet’s magnetic field and atmosphere, astronauts are exposed to intense radiation—sometimes likened to roughly 6,000 chest X-rays. How, exactly, truly extended spaceflight will affect biological tissues is an open question that scientists are working hard to answer, including by recently comparing the chromosomes, gene expression, and cognitive abilities of the astronaut Scott Kelly, who lived for nearly a year on the International Space Station, with those of his identical twin, Mark, who spent that time on Earth.

Several countries and private companies have announced plans to shuttle many more people into the void of space in the coming years—and maybe even install some there for the long haul. That’s an idea that decades of research—from Laika to Kelly—have been building toward. If we do take that step, will our familiar, furry companions return to space, this time by our sides? NASA, which has ambitions to send people to Mars, recently released a fanciful poster showing a helmeted human and a canine pal standing atop a Martian dune. As journalist Marina Koren wrote for The Atlantic, it doesn’t make a ton of sense to schlep a pet dog to the red planet—there won’t be much to sniff, and the soil is too toxic to romp across. But it wouldn’t be a total surprise if we have dogs along on the next frontier of crewed missions. Only this time they wouldn’t be canaries in a cosmic coal mine, but rather companions to offer comfort in space’s cold, distant reaches. The next generation of space-pup swag would be exciting indeed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook