A Whirlwind Tour of Space Race Relics

Places left behind by Americans and Soviets in the race to the stars.

A 1965 stamp depicting Alexey Leonov on the first spacewalk. (Photo: EugeneZelenko/Public Domain)

During the Cold War, the U.S. and the USSR fought for dominion over the coveted title of World’s Most Powerful Country. But the conflict didn’t just stop at Planet Earth. The missile proliferation between the two countries turned into a race to get to space. It was a chance to exert ideological control not just over the people of Earth, but over the cosmos. Whoever made it there first would be representing their nation as the best that Earth had to offer.

Earth is littered with vestiges of this contentious rivalry, which paved the way for such innovations as meteorological systems, the International Space Station, and the Internet. Here’s a list of landmarks from our foray into the final frontier, and the one-upmanship that spurred it on.

Laika Monument

MOSCOW, RUSSIA

Laika Monument (Photo: Wikipedia.ru/Public Domain)

Laika was a little dog picked up off the streets of Moscow by the Russian space program, selected because of her sweet face. Though both Russia and the U.S. had sent animals to space previously, Laika was the first to orbit Earth when she launched in 1957. Unfortunately, Laika didn’t return alive—the details are unclear, but it’s believed she suffocated, overheated, or was intentionally euthanized during her flight.

Despite the fact that they denied it for decades to come, Soviet scientists always knew this would be the case. Technician Yevgeny Shabarov recalled that “after placing Laika in the container and before closing the hatch, we kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight.”

Scientists admitted much later that the entire purpose of Laika’s flight was to see if a mammalian body could physically withstand spaceflight. In this regard, the project was a success; Laika did make it to space, albeit without a return plan. This monument erected to Laika in Moscow commemorates her sacrifice, which paved the way for human cosmonauts to come.

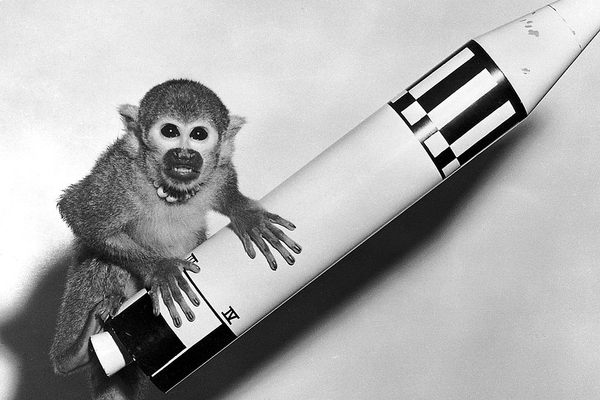

Miss Baker’s Grave

HUNTSVILLE, ALABAMA

The grave of Miss Baker the squirrel monkey, with banana offerings left by visitors. (Photo: mike fabio/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Not all space animals perished in covert death missions, though—some returned alive. One such case is Miss Baker. She was one of many animals sent to space, but the first ever recovered alive by NASA. In 1959 Miss Baker, a squirrel monkey, and Miss Able, a rhesus monkey, were outfitted in tiny space suits and shot out of Earth’s atmosphere. Their flight lasted a mere 16 minutes.

The monkeys landed in the Atlantic Ocean, and were recovered with much excitement by NASA. Their safe return meant that primates could survive space travel. Miss Able died just four days later due to being given too much anesthesia during surgery, but Miss Baker lived a long life after her pioneering mission into space. She spent her retirement in captivity at Huntsville’s U.S. Space & Rocket Center, and upon her death in 1984 was buried in the parking lot. Visitors to her grave typically pay their respects with bananas.

Aerojet Dade Rocket Facility

HOMESTEAD, FLORIDA

A view of the abandoned rocket, through a small hole in its cover. (Photo: Brett Levin/CC BY 2.0)

By the early 1960s, enough tests had been performed that we knew it was possible for humans to attempt space travel. But how were they to get there? NASA began to experiment with different methods of fueling the mechanical behemoths that were to shuttle mankind into space. One of the places experimentation took place was at the Aerojet Dade Rocket Facility outside of Homestead, Florida. The testing grounds were in the middle of the Everglades, hidden from the Russians.

Ultimately NASA ended up using a different kind of fuel than what Aerojet was testing, and the facility was abandoned. But when you’ve got a failed secret rocket in a hole in a national park, it’s difficult to find someone to take it off your hands. No attempts to repurpose the land ever took off, and so the facility, rocket and all, remains as secluded and abandoned as ever.

Ham the Astrochimp’s Grave at the New Mexico Museum of Space History

ALAMOGORDO, NEW MEXICO

Ham’s gravestone. (Photo: David N. Lotz/Findagrave.com)

A three-year-old chimp called Ham (named for the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center where he received his training) was the first hominid to successfully “man” a flight to space and return alive. Ham was launched from Cape Canaveral on the Mercury-Redstone 2 flight, in 1961.

Despite numerous technical problems during the flight, Ham was able to complete the tasks he had been trained for (pulling levers, pushing buttons) at about the same rate he had on Earth. This gave NASA reason to believe that a human astronaut would be able to do the same. Ham was recovered from the Atlantic Ocean, and his only injury was a bruised nose. He lived out his days at D.C.’s National Zoo, and his remains were interred at the New Mexico Museum of Space History’s International Hall of Space Fame. That is, his remains minus his skeleton, which is on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Baikonur Cosmodrome

BAIKONUR, KAZAKHSTAN

Rollout of the Soyuz rocket for the Expedition 21 mission, September 28, 2009. (Photo: NASA/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Outside the tiny village of Baikonur, the Soviets were planning something big. The Cosmodrome was where they had launched Sputnik in 1957, and Laika’s rocket the same year. In 1961, just a few months after Ham’s spaceflight, Yuri Gargarin was launched from the Cosmodrome on Vostok 1, becoming the first man in space.

The facility was literally off the map for many years, using fake coordinates, but American spy planes were able to spot the Cosmodrome from the air. The U.S. was not, however, able to beat them to space. NASA’s first man in space, Alan Shepard, took flight just one month later. Though it’s still in use by the Russian space program today, the Cosmodrome is considerably more public. Visitors can tour the facility and even watch rocket launches (for a hefty price).

Star City

SHCHYOLKOVO, RUSSIA

The centrifuge gravity simulator at Star City. (Photo: Bernt Rostad/CC BY 2.0)

To prepare for his mission, Gargarin and other cosmonauts lived and trained in the mysterious Star City. This place, like the Cosmodrome, wasn’t on maps either. The Soviet space program wanted to keep the little village a secret to ward off theft or even attack by the U.S. Though it was wholly manufactured by the government, Star City was host to a thriving community. The cosmonauts moved there with their families in tow, so the city had post offices, schools, even a movie theater.

Unlike the Cosmodrome, Star City is no longer in use. Instead, it has become a tourist destination. Visitors can see what it was like for the very first cosmonauts to prepare themselves for space, right down to trying on space suits and experiencing zero gravity.

Cosmonaut Grove

BAIKONUR, KAZAKHSTAN

Cosmonaut Grove in the Cosmodrome, Baikonur. (Photo: kilhor/CC BY 2.0)

On a nondescript pathway behind Cosmonaut Hotel, a place for cosmonauts to stay and rest up before their launches, are two lines of trees labeled with plaques from the men and women who planted them. They, of course, were cosmonauts.

Every Russian who’s ever been to space has planted a tree here. Yuri Gargarin’s is the oldest and tallest, while those planted more recently by the Soyuz crews are just saplings. The grove provides a moment of peace before spaceflight—perhaps the cosmonauts find it comforting to leave something behind to grow on Earth.

Monument to the Conquerers of Space

MOSCOW, RUSSIA

The monument features a rocket taking flight with a jet stream behind it, classically Soviet in its minimalism. (Photo: Lynn Greyling/Public Domain)

The Soviets were very proud to have been first to space, to say the least. Yuri Gargarin became an international celebrity the moment he set foot back on Earth. They must have been confident of their success though because plans for this monument, emphatically dedicated to the “conquerors of space,” were set in motion three years before Vostok 1 even launched.

Launch Complex 34

BREVARD COUNTY, FLORIDA

Launch Complex 34, with the rocket cradle at center right. (Photo: brx0/CC BY-SA 2.0)

In 1967, NASA was to launch its first manned mission of the Apollo project, the first attempt to reach the moon. During a rehearsal launch, however, the cockpit caught fire. The flames combined with the pressurized oxygen of the cabin, producing toxic fumes. Astronauts Grissom, White, and Chaffee were killed.

Launch Complex 34 now sits stark and empty. The massive concrete pad still has the rocket cradle at its center, now emblazoned with a plaque to commemorate the tragic accident along with the “ABANDON IN PLACE” graffiti marker on all Cape Canaveral ruins.

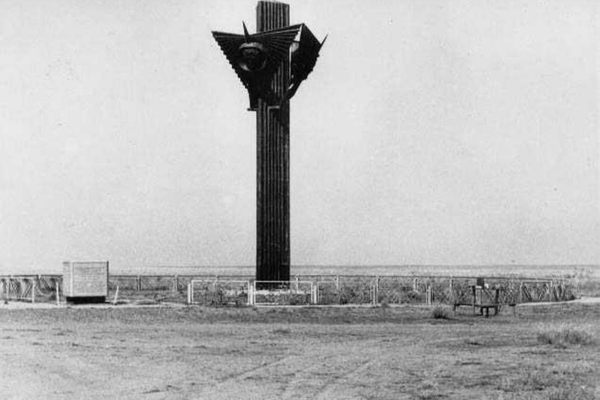

Soyuz 11 Memorial

ZHANAARKA DISTRICT, KAZAKHSTAN

The Soyuz 11 Memorial before being vandalized. (Photo: vikkom0203/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Soviets had tragedies in pioneering the space frontier, too. The 1971 Soyuz 11 mission began well enough. The cosmonauts had broken the record for the most days spent aboard a space station (22), and even after a small fire on the station, their reentry into Earth’s atmosphere appeared normal. But when the recovery crew opened the capsule that had landed in the Kazakhstani desert, they realized this wasn’t at all the case. Cosmonauts Dobrovolsky, Volkov, and Patsayev were dead, their faces black and blue. On detaching from the space station, the cabin had completely depressurized at a rapid rate, and the three men asphyxiated, making them the only cosmonauts to die in space.

The Soyuz 11 Memorial was erected soon after on the very spot the capsule had landed. It was a towering structure in the middle of the desert featuring the engraved faces of all three cosmonauts. In 2012 it was found destroyed by vandals, and since then a smaller monument has been raised in its place.

Alan Shepard’s Golf Club at the United States Golf Association Museum

FAR HILLS, NEW JERSEY

Astronaut Alan B. Shepard’s sock, golf club, and mission patch. (Photo: Courtesy of USGA Museum)

The United States was the first to land on the moon in 1969. Besides Neil Armstrong’s “one small step for man” and the planting of the American flag, perhaps no greater meme has arisen from the Apollo missions than golfing on the moon.

Apollo 14 Commander Alan B. Shepard’s golf session was an unsanctioned experiment not intended to happen during the mission, but when you’re one of a handful of people to set foot on the moon, you’ve got to have your fun. Shepard, an avid golfer, fashioned a makeshift golf club, squirreled it away in his sock, and hit two balls on the lunar landscape. The first veered off into a crater, but the second went for, according to Shepard, “miles and miles and miles.”

The club, the sock, and an Apollo 14 mission patch are on view at the United States Golf Association Museum in New Jersey.

Philadelphia’s Moon Tree

PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA

The moon tree clone. (Photo: Jeremy Thompso/CC BY 2.0)

While Alan Shepard was golfing, Stuart Roosa was orbiting the moon in a command module. He wasn’t alone, though. Before becoming an astronaut, Roosa was a smoke jumper (a kind of parachuting firefighter).

A friend in the Forest Service asked him to bring seeds on the trip to the moon to test the effects of zero gravity on the growth of plant life. Around 500 seeds traveled on the Apollo 14 mission, and were planted and closely studied following their return.

In 1975 and ‘76 all of the moon tree saplings were given away in celebration of the United States bicentennial anniversary. They went to Brazil and Japan, to Monterey, Indianapolis, and Philadelphia. The Philly tree lived until 2011, when it got sick and died. However, the city isn’t totally without extraterrestrial plant life: a clone of the original moon tree was grown in a lab, and its sapling is going strong in the same spot as its parent. While some moon trees didn’t survive, others have grown tall—there might even be one near you.

Timanfaya National Park

TINAJO, SPAIN

The moon-like terrain of Timanfaya National Park. (Photo: Miriela Rodríguez/CC BY-SA 3.0 es)

Devastated by volcano eruptions in the 1700s, Timanfaya National Park was left barren and desolate. It’s so otherworldly, in fact, that it was used when training astronauts for a lunar geological survey on the Apollo 17 mission.

Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics

MOSCOW, RUSSIA

A mythologically flamboyant statue of Yuri Gargarin at the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics. (Photo: Petar Milošević/CC BY-SA 3.0)

By 1981, the fires of the space race had begun to cool. Man had been to space, walked on the moon, and in the mid ’70s the USSR and the US had collaborated on a couple of space missions. At the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics, opened in ‘81 to commemorate two decades since Yuri Gargarin’s spaceflight, one can see objects from throughout the course of Russian space travel, including Yuri Gargarin’s spherical space capsule and the taxidermied bodies of Belka and Strelka, two space dogs.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the space race was off for good. The two countries’ programs diverged. NASA has scaled back its operations and rarely performs manned missions, and the Soviet space program was converted into the Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities, which mostly does experimentation on the International Space Station.

Now, some are turning to private institutions for hopes of space adventures in the future. With proper funding, technology and training, men on Mars might not be so far-fetched.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook