Stingrays, Anteaters, and Orchids: The Year in Newly Discovered Species

Science, please meet this bevy of unusual creatures.

Every year, without fail, wildlife biologists identify troves of plants, animals, and more that had previously been unknown to science. The current tally of described species stands at about 1.5 million (mostly insects—it’s their world, we’re just living in it), and recent estimates suggest there are between 2 and 12 million yet to be identified (including many, many bacteria). So scientists will continue looking—often racing against “anonymous extinction,” when species disappear before we even know they exist—and we’ll continue admiring all the weird and wonderful things that wander in from just beyond the limits of our vision.

Polka-Dot Stingray

This elegant freshwater stingray was found in the middle and upper stretches of Brazil’s Tocantins River. Appropriately named Potamotrygon rex—”rex” being Latin for “king,” due to its large size and regal appearance—it is among the more than a hundred species endemic to the Tocantins.

Skywalker Hoolock Gibbon

This tiny white-browed primate, known as a hoolock gibbon, can be found swinging from high trees in eastern Myanmar and southwestern China. For a long time, it was believed to be an Eastern hoolock gibbon, Hoolock leuconedys, which are found on the eastern side of the Irrawaddy-N’mai River. But in January an international team of primatologists proved that, despite sporting the same iconic white brow, the gibbon is actually physically and genetically distinct from its eastern cousin. They dubbed it Hoolock tianxing, with the common name Gaoligong hoolock gibbon, which literally translates to “skywalker hoolock gibbon” in reference to their swinging habits—and in honor of the Star Wars saga. Their namesake approved:

So proud of this! First the Pez dispenser, then the Underoos & U.S. postage stamp… now this! #GorillaMyDreams #SimianSkywalker #JungleJedi https://t.co/JKCe5kZFmJ

— @HamillHimself (@HamillHimself) January 11, 2017

Elfish Eyebrow Toad

Found in the southern Annamite Range of Vietnam, this new species of toad measures just over an inch, making it the smallest in its genus. They’re found in Southeast Asia’s rare elfin forests, so named for their stunted trees and often diminutive residents. Ophryophyrne elfina—roughly, “elfish eyebrow toad”—can be recognized by the tiny set of hornlike protrusions above the eyes.

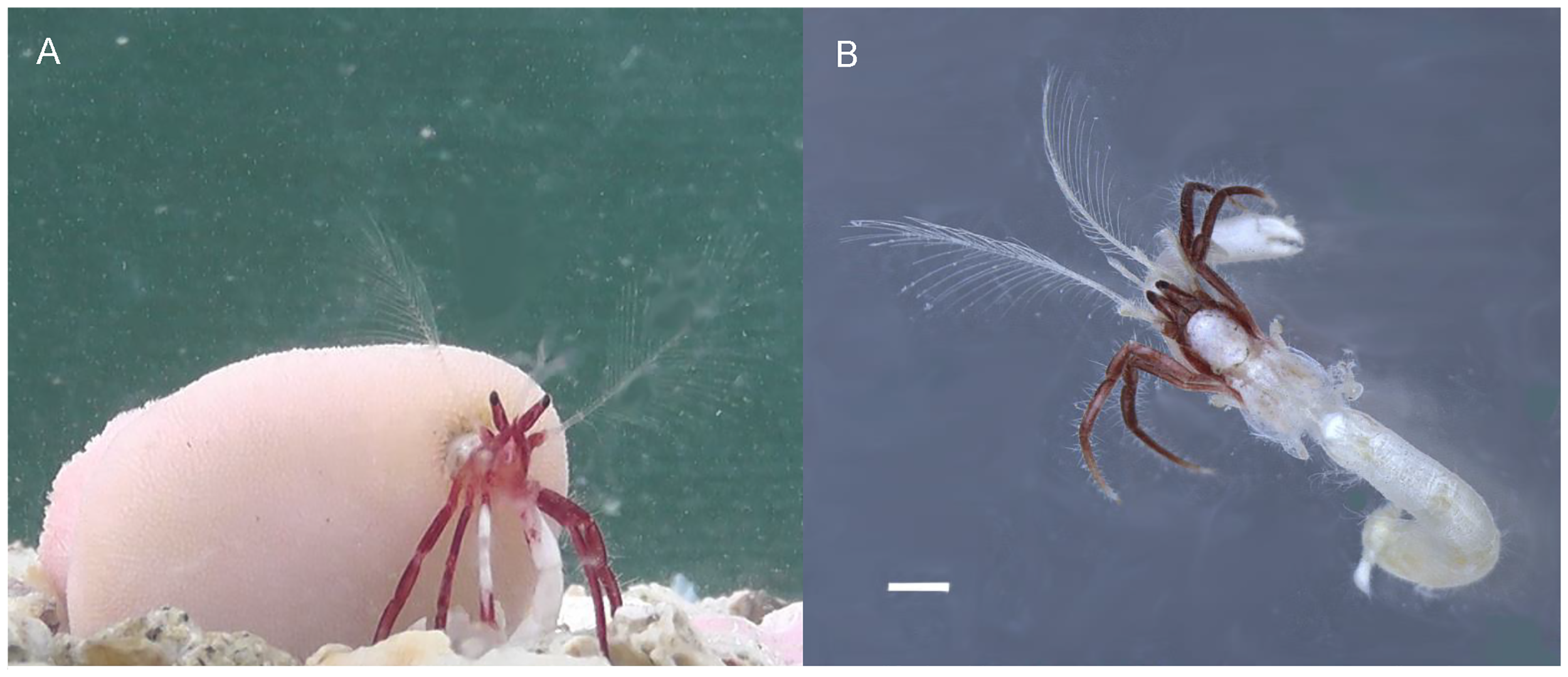

Hermit Crab With an Expanding Home

Hermit crabs are known for crawling around in their little shell homes until they grow too large and need to look for a new one. But Diogenes heteropsammicola, a newly described species of hermit crab found in the shallows of the Amami Islands, north of Okinawa, is done with this constant home-swapping. Instead, it resides in living coral, which grows symbiotically with it. No upsizing required—just crustacean real estate bliss.

Orchid That Smells Like Champagne

Austrian botanists Anton and Christa Sieder were on a hiking trip in remote northern Madagascar when they noticed a beautiful orchid that they couldn’t believe no one had formally reported before. It has a broad, white flower, close to two inches wide—making it the largest known orchid—and a lovely scent, redolent of champagne. Madagascar is known for its wealth of unique orchids, but those northern reaches, which can take days to reach, still hold secrets. A year after the Sieders first reported the find, a botanist from Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, an independent botanical research association, went to see it, confirmed the find, and reported the new species in the Kew Bulletin.

Bird Distinguished Only by Its Song

This is another story of look-alike creatures that turned out to be distinct species. This tiny manakin bird, with a crest of red feathers and a bright yellow splotch across its front, was discovered in Peru in 1996. Scientists immediately noticed that it did not look like any other bird found in the area, and instead resembled ones that live across the continent, in Venezuela. But when they compared the song of the Peruvian manakin to that of its Venezuelan doppelgänger, they realized the birds are different. The newly discovered Machaeropterus eckelberryi, named after a famous bird illustrator, sings a one-note tune that rises in pitch, without the undertones of its cousin. The discovery was reported in the journal Zootaxa.

Electric Blue Tarantula

Found during a night hike in the Guyana rain forest by Andrew Snyder, a doctoral student at the University of Mississippi, this opalescent blue arachnid is more unusual than even its flashy appearance suggests. Tarantulas typically live alone, but Snyder found a bunch of these inhabiting different holes in the same tree, suggesting that it may be a communal species. This specimen was among more than 30 other species that are probably new to science observed during a month-long survey of the Potaro Plateau in central Guyana, on the northern edge of South America.

Grass That Tastes Like Salt And Vinegar Chips

Australian biologists Ben Anderson and Matthew Barrett were walking around the Pilbara, a desert in Western Australia, to collect new specimens of flora, when they stumbled into a eight new types of Spinifex, a grass that grows in sand dunes. It wasn’t until the team made it back to the lab that they realized, by accident, that one of them carried a rather unusual feature: the taste of salt and vinegar potato chips. “The taste was discovered by accident by my supervisor, Pauline Grierson, late one night during lab work. She was sealing envelopes as she was working with the grass and licked her fingers and wondered where the taste came from,” Anderson said.

A Candle of Anteaters

For a long time it was believed that all the anteaters of Brazil’s rain forest belonged to the same species, Cyclopes didactylus. But Flavia Miranda, a biologist at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, was not convinced. After noticing differences in the fur coloration of some of these mostly nocturnal creatures, Miranda spent 10 years scanning Brazil’s forests and natural history museums to collect biological samples. She then led a team of four other scientists to look at their DNA and identify other differences. Thanks to their study, published this month in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, it appears that there could be up to seven different types of anteaters.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook