Is Mordor Based on the Himalayas?

Much of Asia seems to be riddled onto the Lord of the Rings map of Middle Earth.

Where on earth was Middle-earth? Based on a few hints by Tolkien himself, we’ve always sort-of assumed that his stories of “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings” were centered on Europe, but so long ago that the shape of the coasts and the land has changed.

But perhaps that’s too easy and too Eurocentric an assumption; perhaps, like so many other things these days, Tolkien’s fantasy realm too is in dire need of mental decolonisation.

And here’s an excellent occasion: an Iranian Tolkienologist has found intriguing hints that the writer based some of Middle-earth’s topography on mountains, rivers, and islands located in and near present-day Pakistan.

As mentioned in a previous article—recently reposted on the Strange Maps Facebook page on the occasion of the death of Ian Holm—Tolkien admitted that “The Shire is based on rural England, and not on any other country in the world,” and that “the action of the story takes place in the North-West of ‘Middle-earth’, equivalent in latitude to the coastlands of Europe and the north shores of the Mediterranean.”

Extrapolating from the location of the Shire in Middle-earth and from other clues dropped by Tolkien, geophysics and geology professor Peter Bird matched the geography of Middle-earth with that of Europe (more about that in the aforementioned article).

However, seeing Middle-earth as a mere palimpsest for present-day Europe is to place an undue limit on the imagination of its creator. As Tolkien also said about the shape of his world: “[It] was devised ‘dramatically’ rather than geologically or paleontologically.”

In other words, certain parts of Middle-earth may very well have been inspired by other places than European ones. It is telling that it took a non-European connoisseur of Tolkien’s topography to find some examples.

In an article published on Arda.ir, the web page for the Persian Tolkien Society, Mohammad Reza Kamali writes that during several years of cartographic study, “I found that maybe there are real lands [that] could have inspired Professor Tolkien, and some of them are not in Europe.”

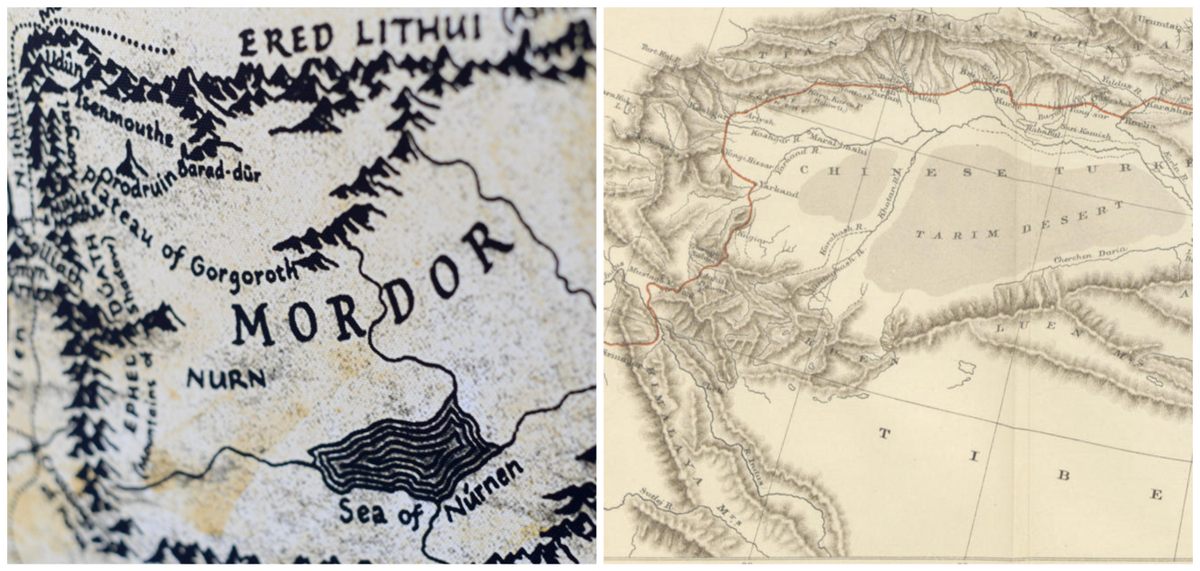

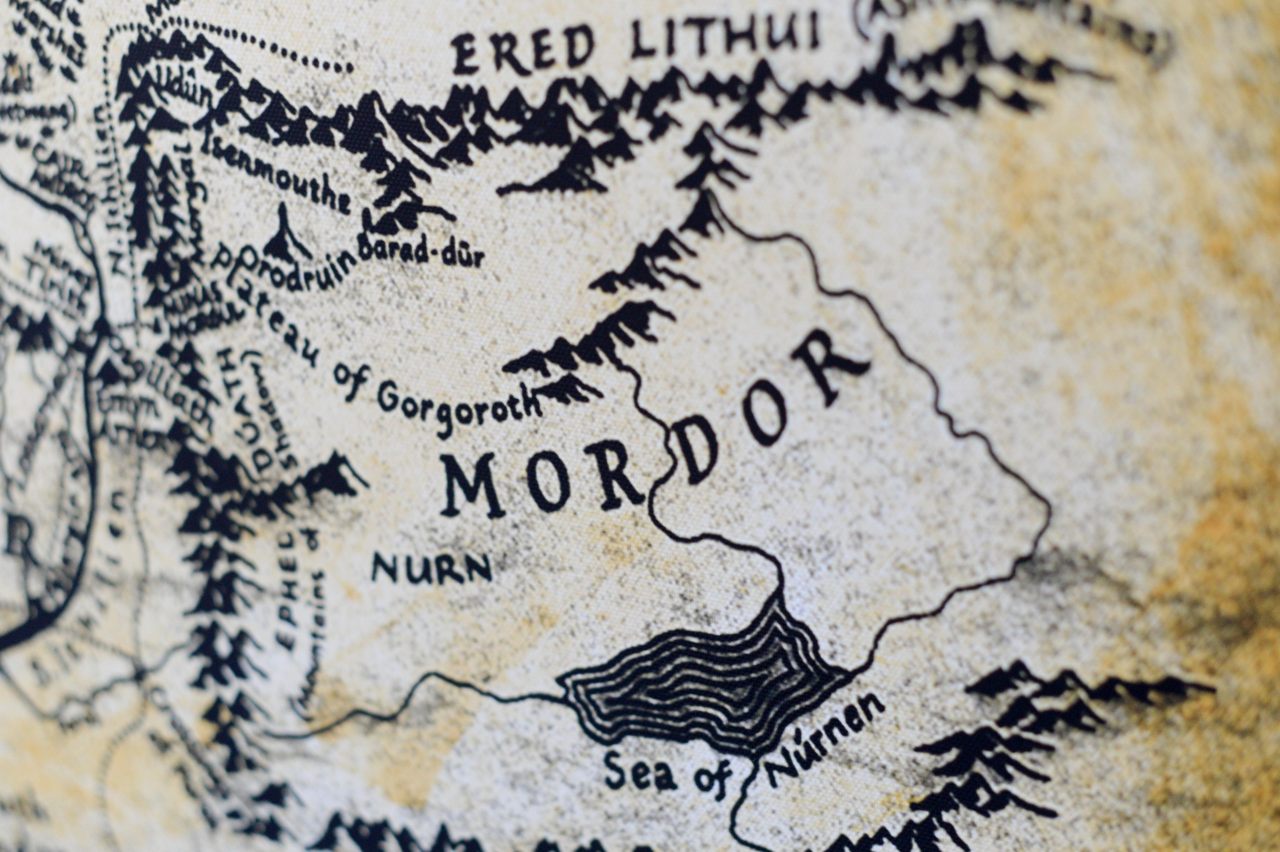

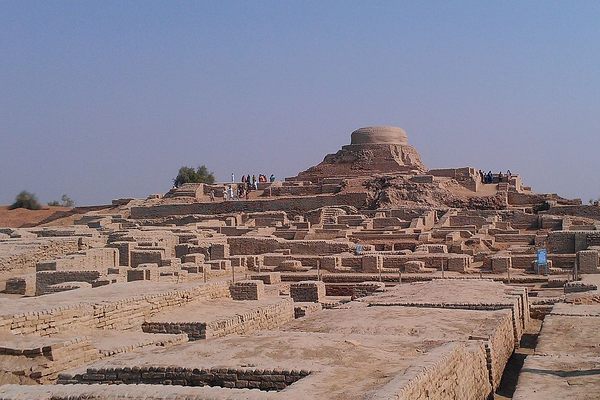

Around 2012, Kamali’s eye stopped when it came across a Google Map of Central Asia that showed the mountain chain of the Himalayas, the peaks of the Pamirs bunched together in an almost circular area, and the huge, flat oval of the Takla Makan desert, bounded to the north by the Tian-Shan mountains.

“I had seen that map before,” he writes. “This is of course Mordor, the land of Sauron and the dark powers of Middle-earth, where Frodo and Sam destroy the One Ring.

In Tolkien’s world, the Himalayas transform into Ephel Duath, the Mountains of Shadow; and the Tian Shan into Ered Lithui, the Ash Mountains. And the circle-shaped Pamirs “are the same shape and in exactly the same corner as the Udûn of Mordor, where Frodo and Sam originally tried getting into Mordor, via the Black Gate.”

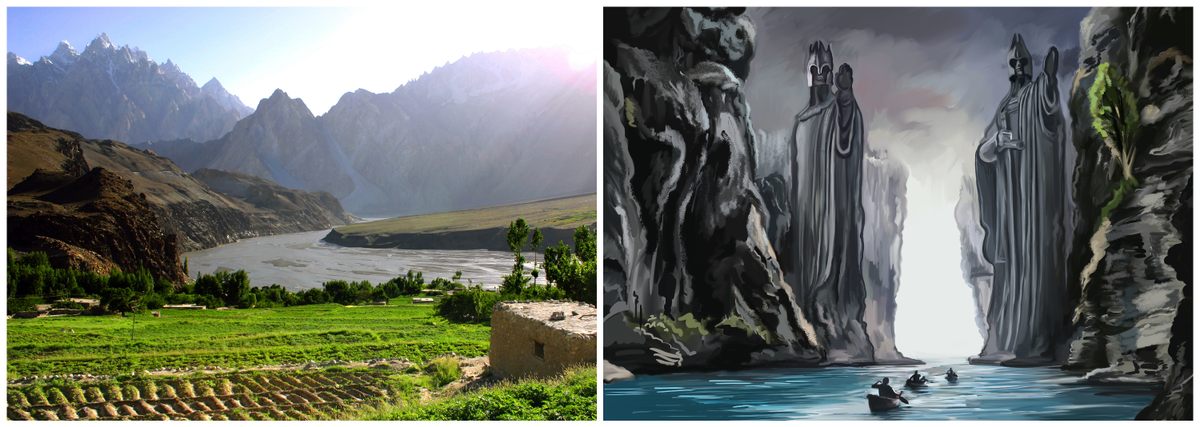

Mulling over these similarities, Kamali became convinced that Tolkien’s map work was heavily inspired by Asia. Looking further, he found more evidence. Consider Anduin, the Great River of Middle-earth, in whose waters the One Ring was lost for more than two thousand years.

On Tolkien’s map, the Anduin bends toward the sea in a shape similar to that of another great river: the Indus, which runs the length of Pakistan. Like the Anduin, it flows to the west of a major mountain chain. A prominent feature of the Anduin is the river island of Cair Andros, just north of Osgiliath. Its name means ‘Ship of Long Foam’, a reference to its long and narrow shape, and the sharpness of its rocks, which split the waters of the Anduin like a prow.

Kamali is not entirely sure, but proposes that Tolkien may have been inspired by a similar-shaped island in the Indus. Now integrated into the Tarbela Dam, which was inaugurated in 1976, it would still have been a separate island in the 1930s and ’40s, when Tolkien dreamed up his map.

Turning our eyes to the mouth of the Anduin and Indus, we see another pair of islands, and Kamali is more certain about the real one having inspired the fictional one. The fictional one is Tolfalas Island, the largest island in Belfalas Bay.

At first glance, it doesn’t seem to have a real-life counterpart near where the Indus joins the Arabian Sea. But take a look at the coastal part of the Indian state of Gujarat. It is known as Kutch, a name which apparently refers to its alternately wet and dry states. In the rainy season, the shallow wetlands flood and Kutch becomes an island – the biggest island in the Gulf of Kutch, and not too dissimilar to Tolfalas Island.

But are these similarities really more than coincidences? Why would Tolkien, who was based in Oxford and steeped in English lore and Germanic mythology, turn to the Indian subcontinent for topographical inspiration? Perhaps because cartographic knowledge of that part of the world was far more general in Britain then than it is now. Until the late 1940s, the countries we know today as India and Pakistan were part of the British Empire. Detailed maps of the region would have been standard fare for British atlases.

Kamali is convinced that the topographical features on Tolkien’s map of Middle-earth are not mere fantasy, but derive from actual places in our world, and were ‘riddled’ onto the map. In that case, we may look forward to more discoveries of Tolkien’s real-world inspiration.

Here’s one example of Tolkienography—if that’s what we can call the effect of actual geography on this particular writer’s imagination—which I gleaned myself, some years ago in East Yorkshire. A local historian told me that Tolkien had been stationed in the area during the First World War, and had apparently stored away some local place names for later use. The name Frodo, he said, derived from a town where he had attended a few dances – Frodingham, a village across the Humber in northern Lincolnshire, not far from Scunthorpe (Scunto? We dodged a bullet there).

Whether that story is entirely true or not is beside the point. As fantasy fans know, any grail quest is ultimately about the quest, not the grail. In fact, to quote Mr Kamali, the treasure is important only because it’s well hidden, “by a clever professor who enjoys riddles.”

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook