The Psychic Tea Rooms of 1930s New York Didn’t Predict All the Police Raids

Tea parlors were the battleground in a war against fortune telling.

On April 17, 1929, Mikette Cuba was fined $100 for a most unusual crime: illegal fortune telling. She had looked in the tea cup of an undercover policewoman, and predicted “a trip across water” and “a tall dark man.” But she made one fatal mistake. She accepted 25 cents in return for the premonition and fell into a New York Police Department trap. Charging money for fortune telling was illegal, and the Police Department was waging war against “tea rooms of occult nomenclature.”

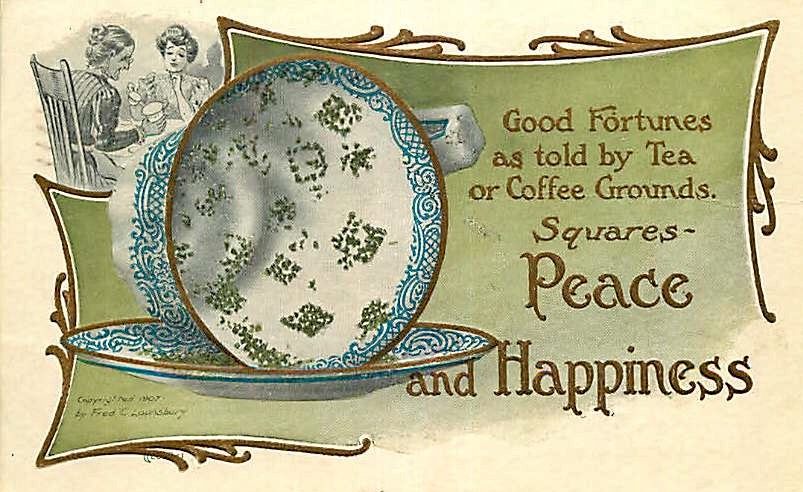

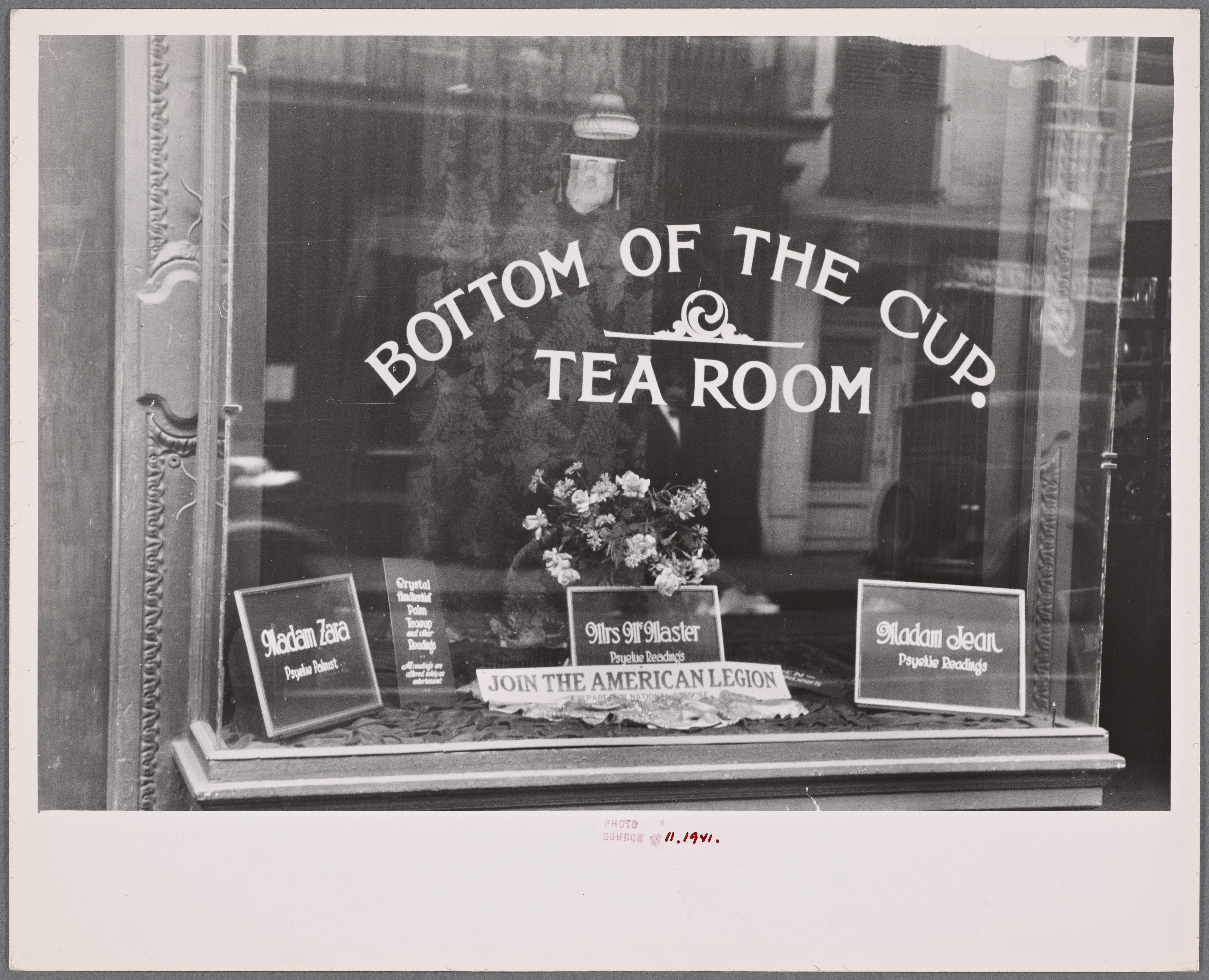

From the late 1920s and onwards, fortune-telling tea rooms flourished in American cities from Pittsburgh to Portland. They emerged out of decades of popular interest in the supernatural, and the most popular theme was a stereotypical depiction of Romani life. Staff wore colorful shawls, fiddlers provided entertainment, and elaborately dressed fortune tellers read tea leaves, palms, or crystal balls for excited guests.

At venues such as Mikette Cuba’s workplace, the Gypsy Tea Room on 5th Avenue, the New York Herald Tribune explained that “a peep into the future is offered as inducement toward purchase of tuna fish salad with mayonnaise dressing, nut bread and pimento sandwiches, a dill pickle, ice cream, tea, and angel cake.”

Legally, these peeps into the future had to be free. American laws against fortune telling had already been on the books for hundreds of years, but by the 1920s, they had been tightened and enforced. Fortune tellers in New York weren’t allowed to take any payment from guests, or even from tea house proprietors. They could only accept tips. Anyone caught straightforwardly telling fortunes for money was fined under New York’s “Statute of Prediction” or charged with disorderly conduct.

This was how Mikette Cuba got in trouble. Two weeks before Cuba’s conviction, Policewoman Mary Vaughan went undercover at the Gypsy Tea House to catch a fortune teller in the act. Vaughan and fellow officer Lillian Harrison were at the forefront of the department’s efforts to target the city’s tea room fortune tellers. Since tea rooms were largely a female space, policewomen took the lead in gathering evidence against fortune tellers.

The city’s fortune-teller vendetta had classist and paternalistic undertones. Jan Whitaker, in her book Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn: A Social History of The Tea Room Craze in America, writes that fortune-telling tea rooms were entertainment for working-class women. As the trend gained steam, in 1931, the New York Times accused fortune tellers operating out of tea rooms of causing “a wave of melancholia among women” because of their frightening prophecies. Since a number of fortune tellers were of Romani heritage, much of the media furor was also racially motivated.

Mary Sullivan, the head of New York’s policewomen, told the Herald Tribune in 1931 that the department was receiving complaints from husbands whose wives visited tea-room fortune tellers. Sullivan told the reporter that “it is common practice of these fortune tellers to tell a woman that her husband is friendly with a mysterious blonde.” To Sullivan, fortune telling was an evil, “which we are trying to wipe out.”

In the first half of 1931 alone, 100 convictions were obtained against New York fortune tellers. The American Society of Magicians, perhaps fearing for their reputations, also got involved in the Sullivan-led drive to expose the city’s fortune tellers. The Society produced a letter from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. declaring they had no evidence that fortunes could truly be told. Sullivan herself went undercover to bust fortune tellers, and none of her unfortunate targets, she commented, were “informed by his stars, spirits, or crystal that I happened to be an undercover policewoman.”

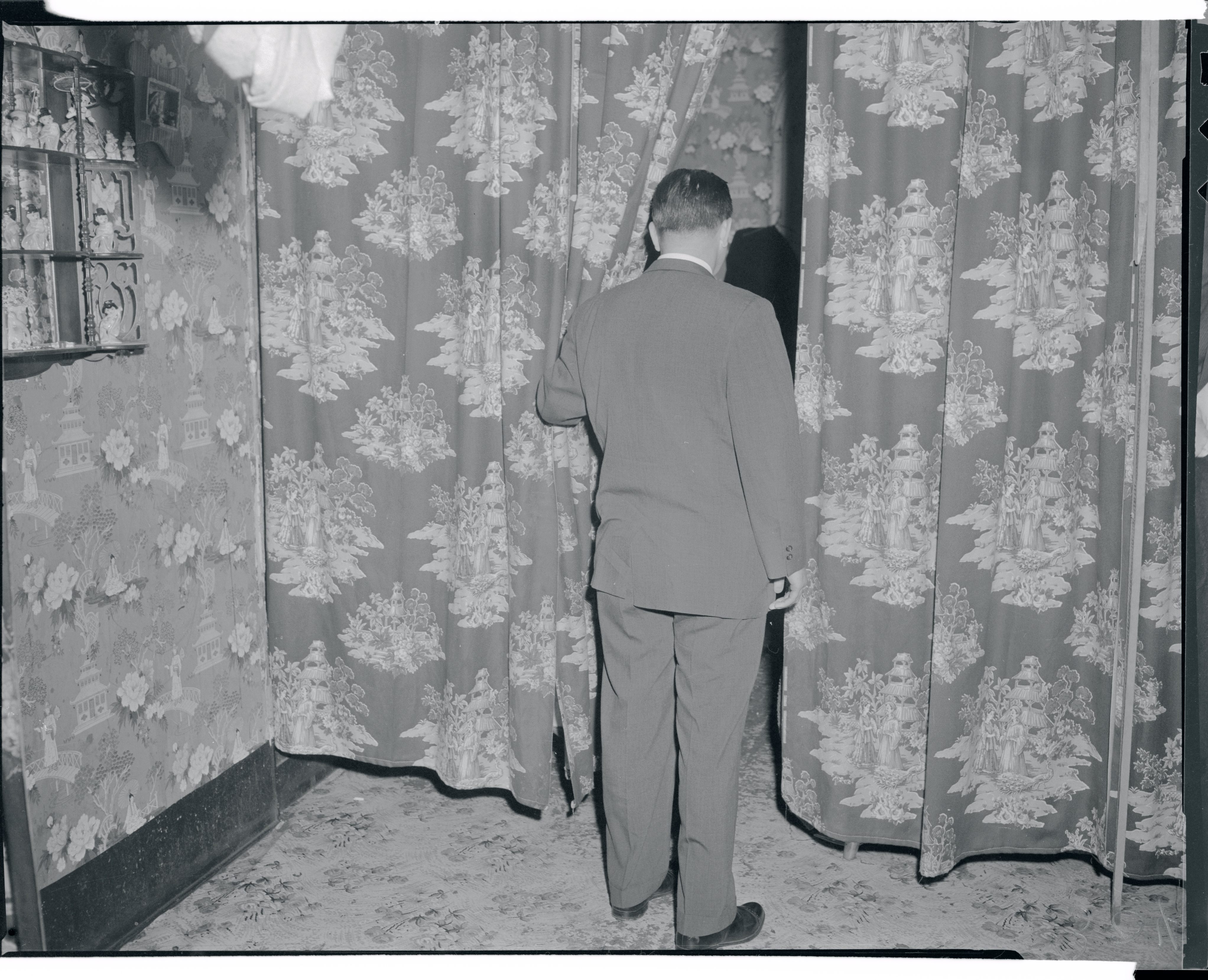

Raids continued through the 1930s. On April 20, 1934, six NYPD policewomen and eight detectives raided three tea parlors, all on the same street. Twelve fortune tellers were brought before a magistrate. The Gypsy Den, the Romany Tea Garden, and the Gypsy Sandwich Shop were the targets. Policewomen had gone undercover as customers, perhaps sipping tea and eating sandwiches, and getting their fortunes told. The policewomen reported that in return “patrons paid what they liked.” It was enough for a raid.

Despite the police pressure, tea rooms remained popular, inexpensive entertainment. In 1935, a hit ballad “In A Little Gypsy Tea Room” reached the top of the international charts, fueling the craze even more. Plus, in a country wracked by the Great Depression, fortune tellers were sources of employment advice, writes Whitaker.

But by the time World War Two started, the raids were taking a toll. On April 1, 1941, fortune teller Anna Meade pleaded guilty to fortune telling after a policewoman busted her. At her trial, Meade explained that she had been warned against telling fortunes at her Gypsy Tea Room in Jamaica, Queens. After stopping her fortune telling practice, her tea room lost so many customers that she started again, leading to her arrest. “I am giving up and moving out,” she said at her trial. Plus, the decades-long popularity of the tea room was fading. By the end of the war, writes Whitaker, tea rooms were “the old lady of the restaurant industry.”

In New York State today, claiming a genuine ability to communicate with spirits or lift curses—and getting paid for it—is a class B misdemeanor. Instead, fortune tellers must declare their prophecies are “solely for the purpose of entertainment or amusement.” Nevertheless, New York City streets are still lined with psychics and card readers. But these days, they advertise with neon signs instead of angel food cake and a cup of tea.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook