Why America’s Thanksgiving Turkey Is So Boring

The bland appeal of the Broad Breasted White.

This Thanksgiving, nearly 50 million turkeys will wing their way onto America’s tables. Many will be packed with butter, some will be swaddled in bacon, a few will be deep-fried. But almost every single one will be a Broad Breasted White, a breed that has existed for barely 60 years. Americans don’t eat the Broad Breasted White because it is delicious. It is the turkey of choice because it is cheap, and because it is very white. Yet this bland bird has ousted almost every other strain to become America’s champion gobbler, leaving many more delicious contenders by the wayside.

Until the mid-19th century, American farmers gave little thought to how they bred their turkeys. The ones you had mated with the other ones you had, or perhaps the ones your neighbor had, or perhaps a tempting fowl from across the way. You might adjust a turkey’s feed for a more succulent supper—Andrew F. Smith, in his book The Turkey: An American Story, describes housewives force-feeding peppercorns to newly hatched chicks—but on the whole, beyond basic husbandry, you let them be.

Then came “hen fever.” In 1850s America, people began to wake up to the idea that by carefully crossing one bird breed with another, you might come up with a superior third—for show or for the dinner table. John C. Bennett, a doctor from Massachusetts, initiated the Exhibition of the New England Convention of Domestic Fowl Breeders and Fanciers. “All who have fine fowl” were invited to contribute, and dozens of exhibitors showed off their best birds. Poultry fancying, as it was called, seized the country. In his 1850 The Poultry Book, Bennett’s publishers describe him as “the first to set in motion this laudable excitement .... to him is due the credit of originating the interest which is now felt in respect to poultry.” The book sparked imitators and successors, as well as reams of agricultural magazines and journals.

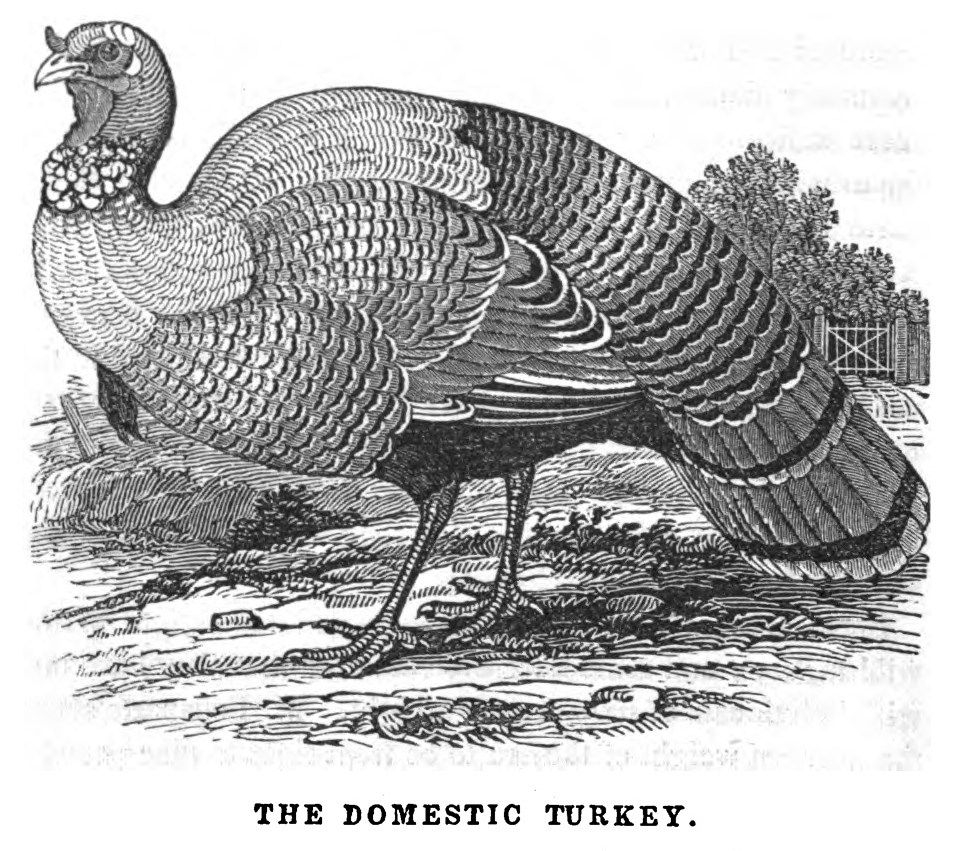

By 1860, the New York Times reported, some of the interest had abated. In a review of a lecture on poultry, the paper noted: “The hen fever which raged so extensively a few years ago was not altogether an evil .… Since its advent the character of our poultry has improved more than fifty per cent. With such results we ought to have a hen fever every year.” While hen fever had mostly focused on chickens, turkeys did not escape attention. Bennett’s book dedicates some pages to turkeys, and quotes H.D. Richardson, a British poultry-raiser, in saying that the domestic turkey is “genuinely wild in all its habits, the unreclaimed denizen of the wilderness.”

Turkey farming soon came into its own. In turkey shows and county fairs, fanciers competed on adherence to breed standards, like a dog show. The breeds varied widely, and often sported bright, interesting plumage. The Bourbon Red, from Kentucky, has striking strips of russet and snowy white. The stately Narragansett is speckled dark brown and white, with a dark arc swooping over the end of its tail feathers. The Bronze turkey could be mixed with others to give its own glossy feathers a sheen of purple, green, or copper. Americans were growing turkeys that looked good and, by all accounts, tasted great. A 1911 edition of the New England Fancier tells how the bird grows fat in its early life on grasshoppers and out in the woods: “Its flesh is the finest and more esteemed than any.”

Then, in the early 1900s, technological improvements turned what had been a backyard industry into something that could turn a serious profit. Refrigeration and the rail industry helped send slaughtered birds careening across the country. They cannily began to charge by the pound rather than by the bird. Profits swelled and breasts inflated like balloons. The focus shifted away from those colorful feathers, unseen by eaters, and onto the biggest breasts possible.

By the 1920s, the Bronze turkey ruled the roost. They were flavorful but, more importantly, they were large. Through careful breeding with British birds, they could soon weigh as much as 40 pounds at only nine months old. But they were monstrous in another sense. Low to the ground, with huge, buoyant breasts, they couldn’t really mate without assistance. As early as the 1930s, artificial insemination took over those duties for them. Other turkey breeds could not compete with this feat of genetic design, and many began to die out.

These birds were the commercial norm, officially named the Broad Breasted Bronze in 1947. But consumers, it turned out, didn’t just prize size. People wanted a bird with lots of white meat, with “clean,” unmottled flesh, and they wanted it cheap, cheap, cheap. By crossing the Broad Breasted Bronze with the White Holland, another popular variety, farmers finally made a bird that grew very quickly, with a hefty breast that was very white. This, as people who savor dark meat know, came at the cost of flavor, but the price was right. Ultimately, cost per pound won out. “They don’t taste of anything,” says Smith, author of The Turkey, “which is why you have to coat them in butter.”

The Broad Breasted Bronze was relegated to second place. The now-ubiquitous Broad Breasted White can weigh 38 pounds at just 18 weeks old. This commercial strain (a cross of two breeds, but not technically a breed in its own right) represents some 99 percent of the turkeys on the market. It is so dominant that its name does not appear on grocery store packaging (though one wonders whether “Plainville Farms,” the name of one large commercial producer, is somewhat tongue-in-cheek). This all comes at a scary potential cost that’s not factored into the price tag—the survival of domestic turkeys. Writing for the Times, Patrick Martins of Heritage Foods U.S.A. explains the predicament: “The future of the turkey as we know it rests on only one genetic strain. And the fewer genetic strains of an animal that exist, the less chance that the genes necessary to resist a lethal pathogen are present.”

The last 20 years have seen a small change, however. In 1997, there were just 1,335 breeding heritage turkeys left in the United States. Extinction seemed imminent, with only a few “old-timers” familiar with their breeding quirks. But groups such as Slow Food and the growth of “foodie” culture have led more Americans to reexamine what they want to put on their holiday tables. In 2006, the last known census counted 10,404 birds, with many hobbyists purchasing heritage chicks. Despite this renewed interest, Smith says, the Broad Breasted White is here to stay, however tasteless it might be. “That’s my humble opinion. But I’d be very happy to be proven wrong.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook