The 1890 Version of ‘Wild’ Saw a 10-Week Slog Through the Carpathian Mountains

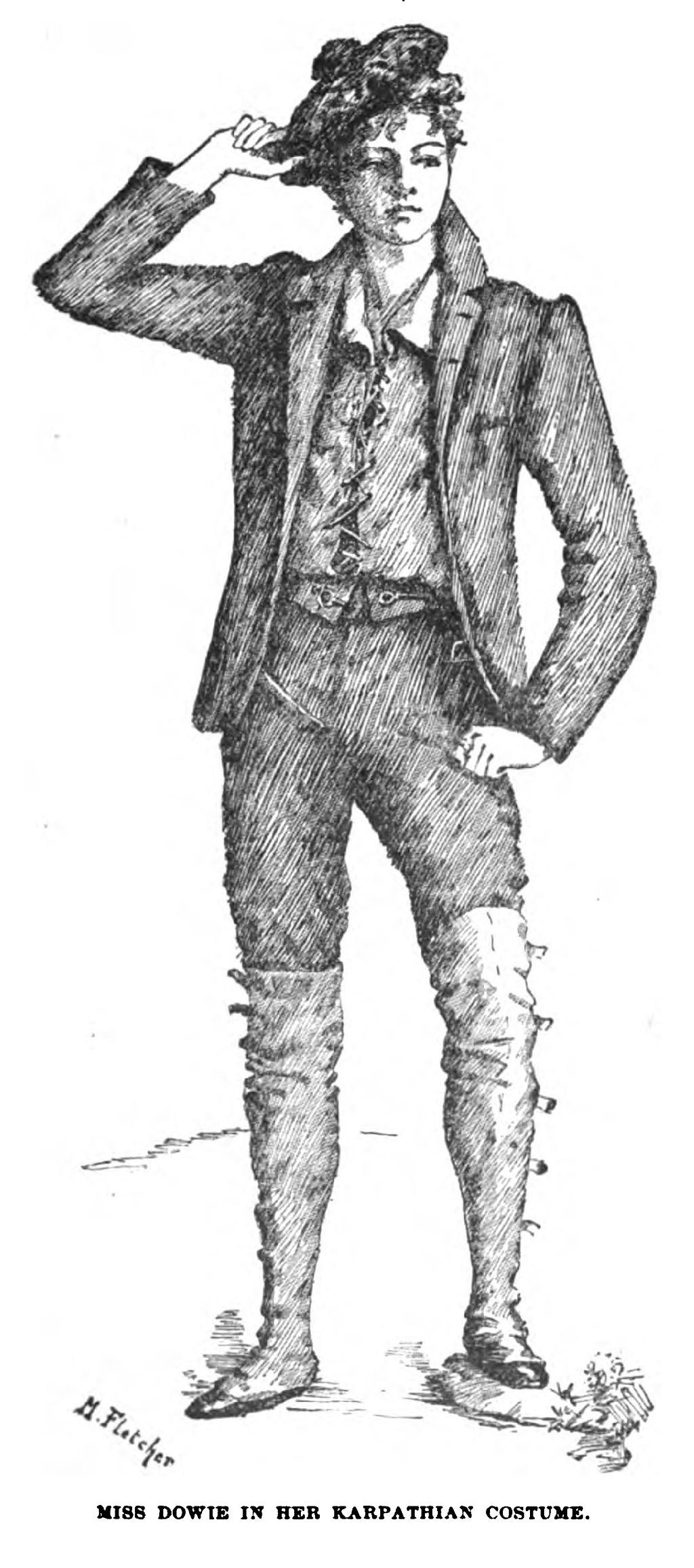

Feminist travel writer Menie Muriel Dowie was understandably irate about her book’s reception.

Menie Muriel Dowie. (Photo: Public Domain)

It was the beginning of the fall in 1890 and 23-year-old Menie Muriel Dowie was the talk of the town.

“This young lady may be taken as the representative of the fearless girl of the period,” wrote the Birmingham Daily Post. Another newspaper described her as “the heroine of the hour in scientific circles.”

Dowie had just delivered a paper to the British Association for the Advancement of Science on her solo travels to the Carpathian Mountains in modern-day Poland. She earned a publishing deal in the following months and wrote a bestselling record of her travels, A Girl In the Carpathians. Gossip columnists fawned at the extraordinary Dowie– dressed in men’s clothes and armed with a pistol–for her brave travails in a remote pocket of Eastern Europe.

But in the face of dozens of positive reviews and column inches devoted to her growing reputation in high society, Dowie wanted to set the record straight. What she wrote was “not a tale of adventure” and what she did during a summer in Poland was not, by the standards held to men, daring or brave. Dowie articulated this in a stinging rebuke to her critics in the preface of the fourth edition of A Girl In the Carpathians.

“Dashing forsooth! Because I smoke cigarettes and say so. Brave, because I go where any young man would go cheerfully blindfold!” Her book was nothing more than a diary of her travels and a summer’s roaming, she said. And she wrote it “with a disregard for conventions she saw no reason to respect.” At one stage, she wrote that she disliked travel, which is not “so amusing as not traveling.”

This is what Kolomyia, where Dowie began her trip, looks like today. (Photo: CC BY: SA 4.0)

This was a time in British society when women travelers like Ellen Browning and Gertrude Bell were making waves for their adventures abroad, but Dowie saw herself differently.

“In many ways she was a woman way ahead of her time in that she wanted to live her life and live a career on her own terms,” says Jane Robinson, author of Unsuitable for Ladies: An Anthology of Women Travellers. “More modern than the modern woman. She didn’t want to be identified with any particular group. ‘I’m me and I’m doing what I want to do.’ That’s ultra modern.”

Born in Liverpool but raised in Scotland and educated for a time in France and Germany, Menie Muriel Dowie was encouraged by her parents to hunt, shoot and fish. She was homeschooled from the age of 14 onwards and once said school didn’t offer girls enough opportunities. Before she decided to become a writer, she wanted to become a surgeon. Dowie sang, recited poetry and started writing for small magazines as a teenager.

Her parents encouraged her to be adventurous and experience life outside of her social confines. Dowie’s grandfather, Robert Chambers, was a famous science writer and early evolutionary biologist. After her father died, Dowie used the money she inherited to travel alone to modern day Poland in the Carpathian Mountains. From the moment she arrived, Dowie made sure she would be taken seriously and adopted a “not-to-be-trifled-with manner.”

The modern day Polish Carpathian Mountains. (Photo: Marctasman / BY: SA 2.0)

Dowie spent 10 weeks moving between villages, climbing hills, crossing rivers and sleeping in the open air. She made detailed notes on the customs and appearances of the people she met. The pistol she carried to warn off wolves and bears was never fired, although did get herself into scrapes; she broke a rib and once treated a girl who cut off the end of her finger chopping nettles.

“I knew no way to deal with the girl and her howling, but I gave her my arm to grip like mad, while I treated the finger with bread pressed into dough, cobwebs from adjacent rafters, and the pinafore,” she wrote.

For her exploits Dowie won the Victorian Wreath in October 1890, a prize for “an act of womanly devotion or daring.” But Dowie found the praise quite patronizing and tiresome.

She wished for a world where women and men would be commended for bravery on equal terms and not, she wrote, “because she wears knickerbockers.”

Later she added, “Ah! The vision of such a future leaves one gasping, does it not?”

Dowie’s anguish may have been directed at reviews like this one, written in Science. The reviewer applauds Dowie for the book about the summer when she “abandoned herself to a life with the natives.” Characters like Dowie are rare, the author continues, and that is a fortunate thing: “she is certainly bright, but independent almost to a fault.”

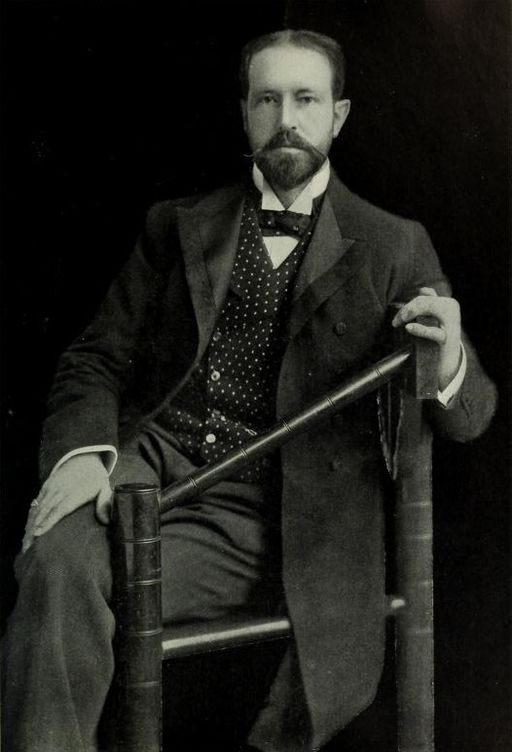

Dowie went on to write fiction and her book Gallia sold well. Her celebrity status increased when she married the traveler and journalist Henry Norman. They had a very public divorce after Dowie had an affair with Norman’s best friend Edward FitzGerald, a mountaineer. Having lost custody of her son, Dowie stopped writing and stepped away from public life. She then became a very successful cattle breeder in England. After traveling in North Africa and Europe, she spent her final years in Tucson, Arizona.

Henry Norman, Dowie’s first husband. (Photo: Public Domain)

Dowie’s maverick status comes in part from her position towards feminism. She became a feminist icon, says Jad Adams, a writer and expert on Victorian Britain, and she certainly, at times, associated herself with feminist causes. But she never identified herself as a feminist, which Dowie hints at in an interview.

“I should like something said to show that I am not a woman’s rights woman, in the aggressive sense; that I do not rejoice in ugly clothes and that I am not desirous of reforming the world, or doing anything subversive of the present agreeable muddle, which is so well suited to lazy women like myself.”

Perhaps this is why she fell into relative obscurity, despite her early fame, notoriety and individualism. “She was a woman going in places and doing things that women didn’t normally do,” said Adams. “For that reason she was certainly a figurehead and someone people looked up to, but she didn’t have any sense of solidarity.”

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook