The 1920s ‘Circus Girl’ Who Fought Sexism—With Tigers

Animal trainer Mabel Stark challenged expectations about women in entertainment.

When the Al G. Barnes circus came to Clovis, New Mexico, in 1921, the Clovis News highlighted one performer whose reputation preceded her. “Woman has achieved many startling things in recent years. She has invaded legislative halls and courts and other hallowed precincts that have always been regarded as the sole property of masculinity,” the reporter wrote. “But Miss Mabel Stark… has done more than this. Not only has she achieved that which no other woman has ever done before her, but her feat has never been accomplished by man either.”

The feat? Taming a full-grown tiger.

“Mabel Stark used to be a trained nurse,” the New York Times reported in 1922. “That was a long time ago, and she had a nervous breakdown… So she took to training tigers. It is much simpler and easier, thinks Miss Stark.” In actuality, Mabel Stark’s life history was spotty, with vague allusions to a life before circuses and little concrete knowledge of her age. But once in the ring, her confidence and experience made it clear that she was not to be underestimated.

Ten years after training her first group of three tigers in 1912, Stark had increased her group to 16, orchestrating them all into an elaborate pyramid in which the last tiger jumped over her head. Some newspapers reported that she would appear in the ring with up to 20 tigers at a time.

Stark’s approach to training tigers was decidedly different from the aggressive, “masculine” method of antagonizing the animals and punishing them with brute force. Instead, Stark used verbal commands and a wooden pole in the ring to “tame” the beasts, further displaying her inventive approach to animal training and her uncanny ability to connect with her costars.

Stark may have been one of the more famous trainers of her day, but she wasn’t the only woman performing with wild animals under the Big Top. In The Circus Age: Culture and Society Under the American Big Top, Janet M. Davis points to this period as one dedicated to the idea of the “New Woman” in performance culture. In the first 30 years of the 20th century, the novelty of women circus performers was crucial for selling their talents to audiences.

Against the backdrop of first-wave suffragette movements and loosening sexual constrictions for white, middle-class women, circus women were seen as exotic, vibrant, and emblematic of a new direction for women inside and out of the tent.

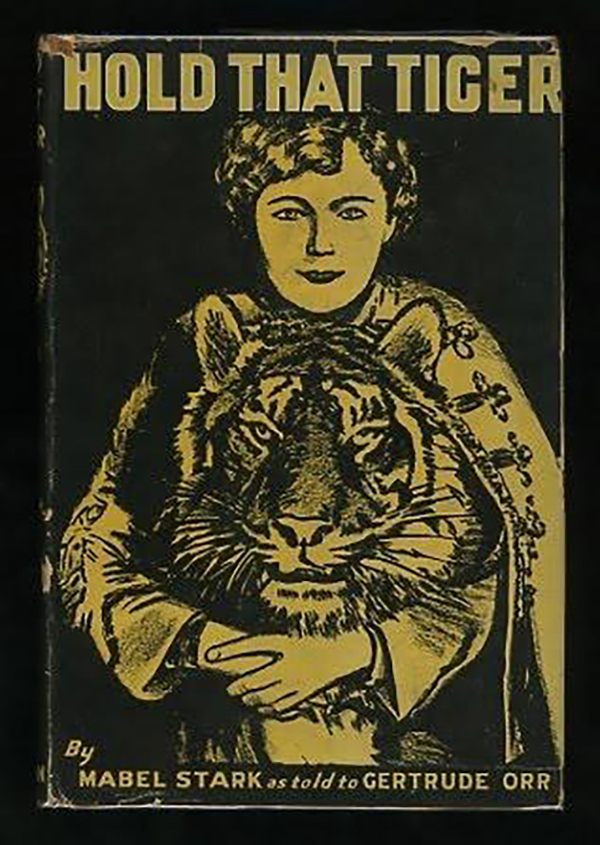

Stark entered the circus world in the midst of these developments. In her autobiography, Hold That Tiger, she recounted that Al Sands, the manager of the Al G. Barnes circus, told Stark that her petite stature and blonde hair would be an excellent contrast with large jungle cats in the ring. This was a visual tactic employed for women like Annie Oakley and May Wirth, whose traditionally feminine appearance acted as a foil to their masculine activities. One of Stark’s most successful acts was wrestling with a single tiger, which also fed into the marketing gimmick of the small girl and the big cat as unlikely companions. In the wrestling act, a fully grown tiger would grab Stark by her head and they would rotate and fall to the ground together until one of them “won” the fight.

The media helped promote Stark’s “small girl, big cat” gimmick by covering the many accidents and injuries she sustained while working with her beloved animals. The reports often focused on Stark and other “circus girls” who were mauled or killed by the big cats they trained. “The smell of blood from the leopard cage set the lions wild and they attacked Miss Stark,” the Herald reported in 1917. “She escaped from the cage with slight injuries,” but her fellow circus girl Martha Florene was badly mauled.

Reporters also burnished the circus girls’ reputation for novelty by telling stories of their eccentric behavior outside the ring. In L.A. area newspapers, reporters regularly covered Stark’s antics, including her sojourn in downtown L.A. with her six-month-old pet tiger, Rajah, on a leash. “Tigers only love people who have stronger wills than theirs,” she was quoted as saying in a 1916 Los Angeles Herald article. It was this confluence of danger and excitement that made Stark and her peers so exciting to watch.

In 1925, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, which had also hired Stark to perform, removed all jungle cats from its acts, leaving Stark to work with horses instead. “I find the horses more difficult to manage than the tigers,” she told the Times, in a piece that called her “the world’s most famous woman animal trainer.” After stints in Europe and a catastrophic injury in 1928 which left her walking with a cane for weeks, Stark returned to the U.S. and worked in film and television, including a job with Mae West on I’m No Angel, which the latter wrote and starred in as a circus performer.

In the 1940s, Stark moved on from circuses to more stationary gigs at Goebel’s Wild Animal Farm in Thousand Oaks, California (later called Jungleland). In 1952, the Times reported that she was a “star” at Thousand Oaks, on the way to her 40th year in the business. She worked with wild cats into her sixties, until she was fired from the Jungleland complex, where she worked until 1968. The Los Angeles Times reported her death on April 22, 1968, an event that some scholars attribute to an overdose.

Mabel Stark, along with many other women who made their living in circus work in the first half of the 20th century, were symbols of possibility for the New Woman, especially when it came to work and autonomy. Stark didn’t just train tigers to jump into a pyramid; she trained public to have different expectations about women’s abilities in entertainment. That’s another feat no man could ever do.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook