The Famous Actress Who Loved Playing a Rooster

Maude Adams was known for being Peter Pan, but her favorite role was that of a preening French rooster.

In New York City, in the winter of 1910-11, two days before the box office opened, people began standing in line to buy tickets to Chantecler, a French play about a rooster. By the time tickets went on sale, the line had grown a block long. In the first three hours of sales, the play sold 3,000 tickets.

There was a simple reason that this philosophical play, set in a barnyard, became the most talked-of theatrical event of the season. It starred Maude Adams, an actress whose reputation and fame in 1911 stretched so far that one critic called her “the most popular person in the United States.”

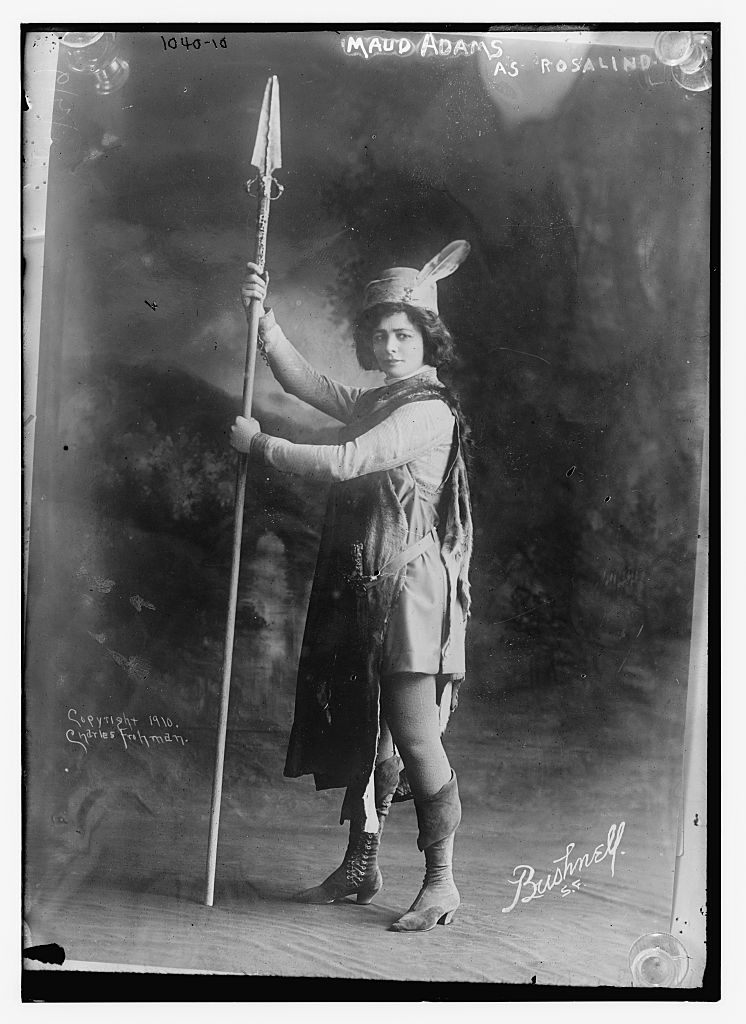

The American production of Chantecler was meant to be a blockbuster. The play’s author, Edmond Rostand—most famous for his Cyrano de Bergerac—had spent 10 years writing it. The American version featured the country’s most popular actress. The production was lavish: Adams and her co-stars were dressed in elaborate costumes that transformed them into barnyard fowl; the stage was set with oversized trees and giant haystacks. Adams, who was most famous for Peter Pan, later said that, of all her plays, she treasured this one the most.

Critics hated it. What were they missing?

Maude Adams, everyone agreed, was incredibly charming. She had been acting professionally since 16, and her breakout role in 1892, when she was 20, showed how funny she could be. (In the scene that stole the show, her character in The Masked Ball pretended to be tipsy in order to get even with her husband, with Adams coming across as hilarious and graceful all at once.) In 1897, she starred in her first play by J.M. Barrie.

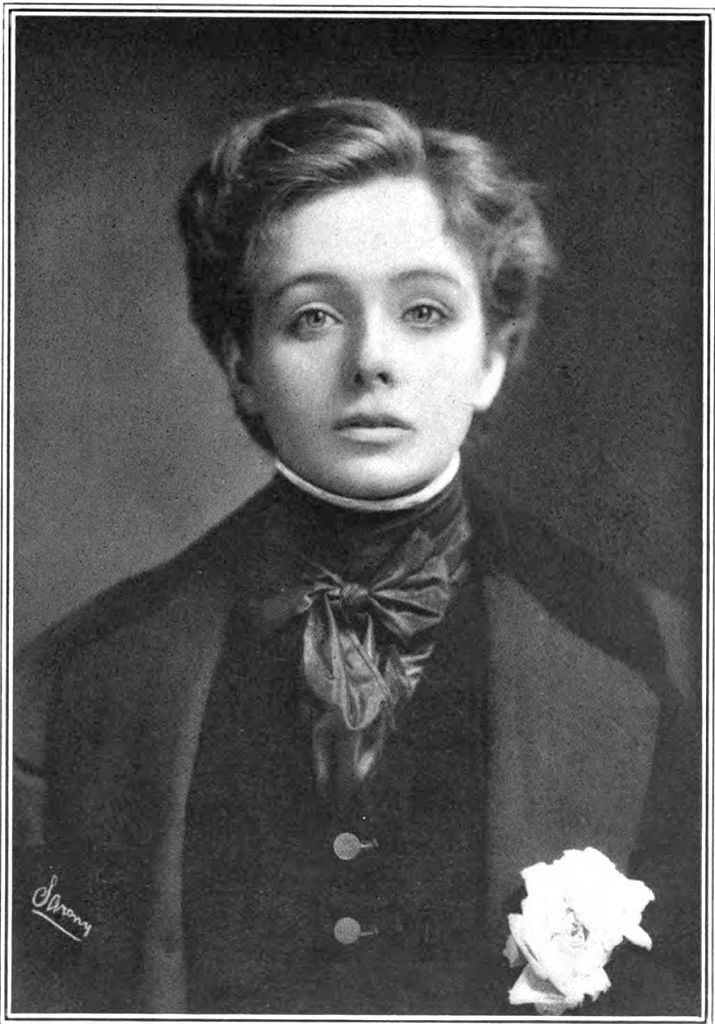

That collaboration would last for the rest of her career, but it was one play, the stage adaption of Peter Pan, that made Adams a superstar. As Peter, she was funny, mischievous, charming, naïve, and moving. She added her own touches to the play, too: the style of collar she designed for her costume would become the popular “Peter Pan collar.”

Peter Pan wasn’t the only show in which Adams played a male character. In 1900, she had starred in another Rostand play, L’Aiglon, as the title character, Napoleon II, the eaglet, son of Napoleon Bonaparte. Rostand had written that role for a woman: in France, it starred Sarah Bernhardt, Adams’ only real rival among the actresses of her day.

Chantecler, though, was meant to star a man. The title character, a barnyard rooster, is a strutting specimen, full of pride. At the beginning of the play, he is convinced that his thrilling song causes the dawn to break each day, and the story follows his philosophical and emotional journey to the realization that the sun will rise without him. Rostand wrote the role for a very “masculine” actor; Chantecler himself was described a “Cyrano in feathers,” a man after the heart of Rostand’s most famous character, the brash and big-nosed Cyrano de Bergerac. But when Adams’ longtime producer saw the play in France, he decided immediately that he should buy the American rights to the show and that Adams should be its star.

When Chantecler finally opened in New York, after months of rehearsals, including special instruction for the actors on making proper fowl-like noises, Adams first appeared on stage in evening dress, to deliver the prologue. After she disappeared backstage, the curtain rose on an oversized barnyard, with a haystack towering over the stage. The sets had been created by a star-studded team of designers, who’d worked on some of the city’s great monuments—the Brooklyn Masonic Temple, the vaulted ceiling at Grand Central Station. When Adams reappeared, fully feathered, as the Rooster, she would have been dwarfed by the sets, made to seem smaller than human, akin to actual barnyard creatures.

In New York, the show sold out. Adams would eventually perform the show 320 times in 89 cities. Financially, it was a success. But the reviewers who saw the show uniformly hated Adams’ performance, because she was a woman.

“Chantecler is essentially a masculine role…and Miss Adams is essentially a feminine actress,” one wrote. “Nothing could be more incongruous than a woman’s essaying to play a character whose strength and value depend on upon masculine virility,” wrote another. “The actress was charming and delightful as Maude Adams, but never for a single moment was she Chantecler. She did not even give the remotest suggestion of the character—no woman could.”

A third: “Chantecler is brutally masculine or he is nothing. He is aggressive, arrogant, masterful, with a powerful, virile voice and a lustiness that betrays itself both in his strut and his crow. How much of all this does Miss Adams suggest? Nothing. Her frail, womanly physique did not permit her to even hint at the possibilities of the part.”

It’s hard to imagine what she could have done to impress them, though: they had imagined the part should be played in a way that she never could have fulfilled. One critic summed up the general critical sentiment: “Miss Adams’s desire to appear in the title role is, of course, impossible to understand.”

Adams’ own judgment of the play was the inverse of the critics’. “Of all the plays that were trusted to my care, I loved Chantecler best, and then came Peter Pan,” she told a friend later in life.

Adams’ loyalty to Chantecler may have had to do with her rivalry with Bernhardt, who had wanted to play the role in the French original—one account has it that she “literally fell on her knees before [Rostand] begging the privilege of presenting her as Chantecler.” If Bernhardt had owned L’Aiglon, Adams could own Chantecler.

But more than 100 years after Chantecler first premiered, it’s not so hard to see what might have attracted Adams to the role. Chantecler lives to perform: to him, it is everything that matters. In the course of the play, he had to confront the realization that his voice is not the most beautiful, and he has to decide whether to trade his dedication to performance for the possibility of love. In the end, he chooses to continue his performance—even if the sun doesn’t rise because of his song, he realizes, he has a duty to signal the importance of the dawn to the other animals.

Like Chantecler, Adams dedicated her whole life to performance, never marrying. To her, Chantecler was “the story of an idealist going forth into the world and getting the edges rubbed off his ideals by the stern realities of life,” one contemporary reporter wrote. “But she believes that the cock’s steadfastness to these ideas, even when he learns that his part in the scheme of things is not as important as he thought it was is the most lasting lesson in the play.”

Perhaps as a woman, limited in her art by her gender, she identified with that.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook