The 1942 Ghost Blimp That Bewildered a California Town

The remains of the missing crew were never found.

On August 16,1942 something very strange happened in Daly City, California, a quiet suburb near San Francisco. Around 11:30 a.m. a sagging Navy blimp descended from the sky and headed for Bellevue Avenue.

“It looked like a big broken weiner,” a fireman recalled for the San Francisco Chronicle in 1979.

It perched fleetingly on a rooftop before drifting off and snagging in a tangle of power lines. The blimp sheared through the wires and sent arcs of electricity into the air before coming to rest on the ground. The engines were smashed into the pavement, one of them clogged with earth. The propellers were bent. Gasoline poured into the street.

Chaos reigned on Bellevue Avenue. People ran from their homes and raced to the scene. The crowds were met by police and firemen who held them back and rushed to save the crew.

But there was no crew to save.

To the rescuers’ befuddlement, the gondola of the blimp was unmolested. The pilot’s parachutes were tidily put away in their normal spot, the lifeboat remained. The cap of one of the pilots still sat on the instrument panel. The blimp was in perfect working order, down to the radio. There was even a bomb still attached to the blimp, and naval officials would later assure everyone that there was never any danger because it would only detonate in water. (This is fortunate, because a second bomb did not remain attached—it tumbled from the blimp and landed on a golf course near San Francisco.)

A photographer snapped a photo of the crash, an incongruous image of the blimp gondola jutting into the air from a city street, flanked by crowds, cars, and houses, its deflated gas bag drooping like a cape behind it. The image was reproduced in newspapers nationwide, most often with the tantalizing caption: “Mystery Surrounds Blimp Crash at Daly City”.

Search parties were dispatched—Naval servicemen hunted for the men by land, air and sea. A Navy spokesperson told the United Press that they were completely without clues. Where was the missing crew and what had happened to them?

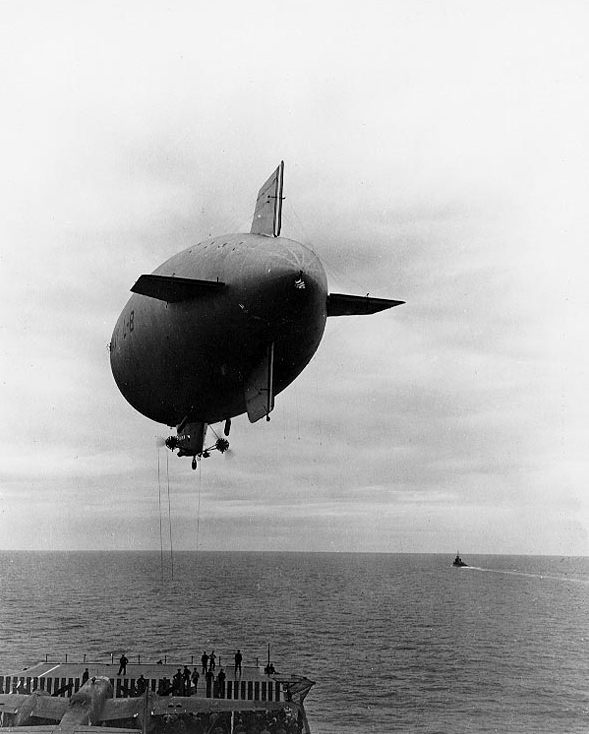

The U.S. had entered World War II in 1941, and the Navy deployed blimps to do routine submarine patrols along the coast. This blimp, called the L-8, belonged to the Navy and had departed from Treasure Island, a manmade naval outpost in the San Francisco Bay, early that morning. It was piloted by two men, Lieutenant Ernest DeWitt Cody and Ensign Charles E. Adams, both men with years of experience aboard lighter-than-air ships. They were in good spirits and health on the morning of the 16th, a colleague reported at an inquest just days after the incident.

Earlier that day, a short message was radioed from the blimp to Treasure Island: “Am investigating suspicious oil slick—stand by.” An oil-slick could be a tell-tale sign that a submarine was in the area. It was the last message the crew would send.

Even though the gondola was eerily intact, there were a few odd things about the state of the blimp (aside from the fact it was crewless and run aground in a city street). The door was open and fixed by a latch to the outside of the car to keep it open. Typically, this door would never be opened during flight and it could only be opened from the inside by the crew. The engines were stopped, which suggested that maybe the pilot wanted to slow the blimp down. On every flight, the crew would bring a weighted briefcase of classified documents with them, and in case of emergency, they were to hurl these overboard. The briefcase remained, which suggested there was no emergency or that whatever had happened took place so quickly that the men couldn’t react. (There were also two life-vests missing, but it was common for men to wear these when sailing over water.)

The L-8 did not go unobserved before it plunked down on Bellevue Street. Civilians and officials spotted the ship, including a member of the Navy’s Armed Guard Unit, who was aboard the cargo ship Albert Gallatin. During the inquest, he told his interviewer that he had watched the blimp circle nearby waters above two flares (which the Navy determined had been dropped by the blimp)—behavior consistent with investigating an oil slick.

“We figured by that time it was a submarine,” said Wesley Frank Lamoureux. “From then on, I am not too positive of the actions of the dirigible except that it would come down very close over the water. In fact, it seemed to almost sit on top of the water.”

Believing there might be a submarine nearby, the Albert Gallatin sounded their general alarm, manned their guns and sped away from the scene. The last Lamoureux saw of the blimp, it had pulled its nose up from the water, apparently preparing to ascend.

Puzzling witness accounts found their way into the press and added to the air of mystery surrounding L-8. A telephone operator named Ida Ruby was out for a horse ride near the beach when she spied the blimp through binoculars. She told United Press that she was “quite sure” she saw three men in the gondola. An official testified at the inquest there was no possibility of a stowaway.

Just two days after the crash, on August 18, the Navy concluded that there was no good reason for the men to leave their ship voluntarily; there had been no fire, no attack, bad weather, no technical malfunction. The theory they offered was this: Perhaps the gondola door malfunctioned, allowing one of the men to fall out. Hoping to rescue him quickly, the second crewmember piloted the ship close to the water, where he also fell overboard. They both perished. This remains and theory, and the actual fate of the airmen unknown because their bodies were never found.

Not surprisingly, this story has not satisfied everyone. Alternative theories abound: The men got in a fight and fell overboard. The men went AWOL. One man was a spy. Both men were spies. They were taken captive aboard a Japanese submarine. They were abducted by UFOs.

But the most probable theory is the most boring, which is also the most frightening. Because UFOs are exotic, but slipping and falling is not, which means death is one silly mistake away for all of us. As one reporter noted two days after the crash, “Had the two men remained in the cabin they could have stepped to the street without injury.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook