The Amazing Pop Iconography of Vintage Firework Art

Even the Seven Dwarfs can be explosive (Image: Epic Fireworks/Flickr)

Firecrackers are designed to be set off. But before they’re lit up, they need to find a buyer. In order to distinguish one bundle of flammable material from another, fireworks manufacturers have produced a riot of labels and characters meant to appeal to explosion-loving fans.

Fireworks can only do so much. They go upwards into the sky, and they explode, in a limited palate of colors and shapes. Fireworks art knows no such limits. Over the decades, manufacturers, almost always based in Asia, have labeled their products with zebras, bears, alligators, peacocks, hawks, pigeons, giant squid, buffalo, Father Christmas, fox hunters, Batman, voodoo witches, werewolves, racecars, Tarzan, Samson, and, of course, rockets—so, so many rockets. There were pictures of childhood and spirits and pop culture icons, pictures of the Wild West and images of outer space. They used whatever it took to convince the buyer (most likely a young man) that this was the firework that he wanted to light up.

These labels were never meant to be saved. They were generally drawn by Chinese artists who received no credit, and intended to be burnt up or thrown away. But across this country and in China and Macau, there are people who make it their business to collect these mini-pieces of pop art.

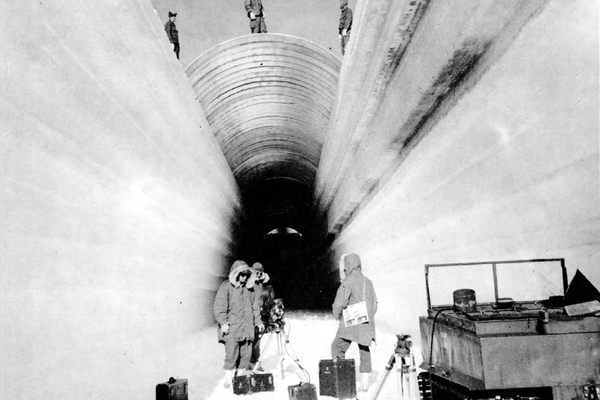

A rarity. (Image: Epic Fireworks/Flickr)

“I collected firecrackers, and I never really cared to light them off,” says Bruce Dillin, a collector based in northern New Jersey. “But the labels always meant a lot to me.”

Firework art contains “delights not found on government-issued collectables such as currency or stamps,” including little jokes and funny misspellings, writes Hal Kantrud, a collector in North Dakota.* “Add to these features the childhood memories of fun on 4ths of July long past, and you have nostalgia personified.”

Fireworks and their labels are organized into classes. Class 1, for examples, contains fireworks and labels made in China or Hong Kong before 1950—before Mao created the People’s Republic of China. Back in the early part of the century, according to Kantrud, there were only a few, relatively simple brands, including Eagle, Dragon and Uncle Sam, but after WWI, the labels became more artistic, featuring “modest maidens, bouquets of flowers, high deities, and gentle animals.” By the 1940s, the firecracker business in America was booming, and brands with names like Duck, Camel, Lion, and Zebra were cornering the market, until the political upheaval in China moved the production center for firecrackers to Macau, then a colony of Portugal.

A more recent label (Image: Epic Fireworks/Flickr)

China eventually tried to rekindle its firework industry, but it’s these older labels, made without warnings or even cautions, that are most desirable. In Firecrackers: the Art and History, the authors index labels according to rarity: Skipper, Father Christmas, Tarzan, Thunder Cloud and Pioneer are classified as “very rare.” Eventually, American regulators starting putting restrictions on fireworks, and manufacturers starting adding cautions that warned users: “Do not hold in the hand after lighting.” (On one such label, the illustration shows a knight holding a bolt of lightning in his hand.)

There are enough brands and variation to keep a collector busy for decades, though. “My collection of labels from 500-600 brands of firecrackers is little more than a representative sample,” writes Kantrud. “I have seen labels from hundreds of other brands and there likely are hundreds more that have been lost forever.”

Perhaps the largest trove of labels once belonged to George Moyer, a collector based in Pennsylvania. But in 2012, he auctioned off his collection, of more than 1,300 items. Some lots—usually containing actual vintage fireworks, not just the labels, went for upwards of $3,000. (A single label, according to CBS, can go for $1,000.) All in all, Moyer made more than $438,000, the Washington Times reports.

“Is it valuable? Somewhat,” says Dillin, the New Jersey collector. “To us.” Anybody else, he says, would have a different reaction, particularly to the vintage fireworks that sometimes are still attached to the labels: “Just light ‘em.”

China didn’t entirely corner the market. (Image: Epic Fireworks/Flickr)

*This sentence was updated to change South Dakota to North Dakota. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook