The American Government’s Sears-for-Spying Payment Plan

Sears, 1966 (Photo: Mike Mozart/Flickr)

In 1966, when Jon Wiant arrived in Hue, a palace-filled city in central Vietnam, American involvement in the war between the south and the north had recently begun to escalate: the year before, the U.S. had deployed 200,000 Marines to the country and started bombing North Vietnam. Wiant was an intelligence officer, recently deployed to the border between Vietnam and Cambodia, and when he arrived in Hue, he took over a small operation that had Vietnamese agents bringing information about the Viet Cong. And he faced a very basic problem: how to pay his agents and recruit more.

Wiant came up with an ingenious solution, as he recalled decades later in Studies in Intelligence, a journal for intelligence professionals (from which the details of this story are drawn). He would pay his agents in gear from the Sears catalog.

Khe Sanh, where some agents worked, in 1968 (Photo: U.S. Marine Corps)

Among the expenses that clandestine operatives rack up in the field, payments to their agents—the well-placed men and women they recruit to pass on information or otherwise assist them—are among the most unusual. Most expenses for CIA and other intelligence officers look like any business traveler’s: they buy meals, stay in hotels, and rent cars. But while some agents are more than happy to accept monetary compensation for their efforts, others have more unusual requests. Sometimes they want to avoid attracting attention with an extra stash of cash; sometimes they want items (everything from particular ballpoint pens and fishing equipment to guns and prescription medication) that they can’t easily acquire themselves.

Often, agents know what they want. What makes this case somewhat unusual is that the intelligence officer came up with a very unique payment scheme and sold his agents on it.

For Wiant’s cohort of agents, money didn’t work as an incentive because they rarely used it: they were “hunters, rattan gatherers, aloe wood collectors, or charcoal makers,” he wrote, and for the most part, they participated in a barter economy. Before Wiant arrived, his predecessor had started paying the agents in rice, along with other food or basic commodities. This had been more effective than offering compensation in piasters, the local currency.

But the system had a flaw. The local district chiefs in the areas where the agents operated had started siphoning away a portion of the agents’ earnings. A plan to mollify the district chiefs with Johnny Walker had worked briefly—until local missionaries objected.

A man who Wiant calls the “best of the Vietnamese agent handlers” did have some success giving one agent a canvas hat as a bonus, and that’s what gave Wiant the idea of sending that agent handler back out into the field with a Sears catalog, the most recently one available, which his wife had recently sent over. Wiant flagged a few pages of possible interest and created a basic “pay scale” connecting items of a certain value to missions of a certain length and danger. But he also told the handler to let his agents page through the catalog.

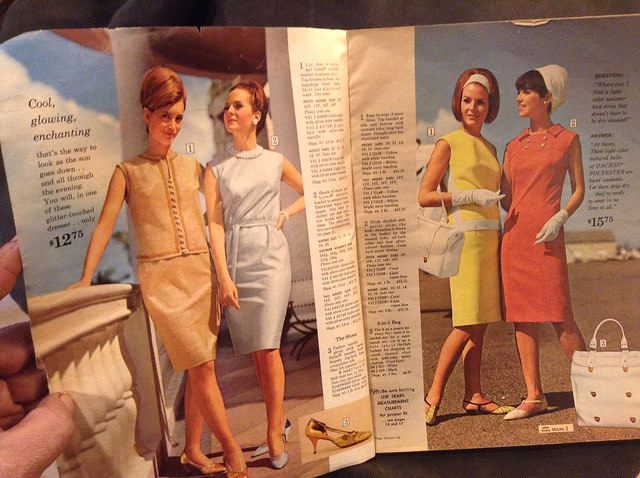

From the 1966 Sears summer catalog (Photo: Mike Mozart/Flickr)

The handler came back with an order: “six boys’ size red velvet blazer vests with brass buttons.” For each of the blazers, Wiant would get an agent in the field for 20 days.

The system was a great success. For months, the agents and their handlers negotiated deals where they’d receive Sears gear, including belts and denim jackets, in exchange for intelligence work. The reports they brought back were valuable, too. (The people who oversaw his budget, Wiant reports, were less pleased about this creative form of payment.)

The system only lasted until 1967, when it started to become too dangerous in the area in which the agents had been working for anything in the Sears catalog to compensate. Marines had begun covering the area, too, and providing their own intelligence. But while it was in place, the Sears for spywork system was a success. The agents even, at one point, ordered “a large bra,” Wiant wrote—they stuck it on a bamboo pole and used it to harvest fruit.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook