The BFFs Who Ruled Silent Hollywood

Mary Pickford and Frances Marion, 1918. (Photo: Photofest)

Mary Pickford was America’s original sweetheart, the it “girl with the golden curls,” who became an international superstar playing plucky children filled with innocent wonder. Frances Marion was a patrician sophisticate, “just as beautiful as the stars she wrote for,” who was continually told that she was wasting her looks on writing. Together, they would become one of the powerhouse teams of silent Hollywood, pioneers leading the way through the Wild West of early film.

They met on a blustery Los Angeles day in 1914. Frances Marion was an aspiring young artist. She had come to L.A. to design movie posters after a stint as a reporter and illustrator for the San Francisco Examiner, her hometown paper. At a party she had met Owen Moore, a matinee idol and Mary Pickford’s current husband. Believing Mary would be interested in Frances’s illustrations, Owen arranged a meeting between the two.

On the appointed day, the Santa Ana winds blew so furiously that Frances had to leave her portfolio at home. She arrived at the makeshift studio empty handed. Her nerves got the best of her as she was led to the small, dark shack where Mary, already a superstar beauty with the “mind of a captain of industry,” was splicing film for her latest picture. Years later, Frances recalled their first meeting:

“Come in! I’ve been expecting you,” said a firm clear voice, and in a deeper tone than one would associate with the childlike image Miss Pickford presented on the screen…She seemed such a little girl that I felt more like putting my arms around her than shaking hands formally. “You’re Frances,” she said, extending her hand. “Hello.”

“Hello, Mary.” I stood there, holding her slender little hand in mine, all the charming compliments I had prepared fleeing before the frank appraisal in her eyes. And as she looked at me I became aware that a strange watchfulness lay behind her steadfast gaze…

”I think we’re going to be friends,” Mary said, breaking the long silence that had fallen on us.

“Thank you Mary,” I mumbled, feeling exactly as if I’d just had my brain X-rayed.

Mary Pickford with a camera, c. 1916. (Photo: Library of Congress)

To break the tension, Mary began to teach Frances how to edit film. Frances had found her mentor, and Mary had found the woman she would call “the pillar of my career.” At only 22, Mary, who had been acting since she was a child, was already producing and occasionally writing her own movies.

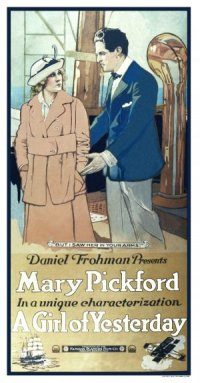

After a stint working for the pioneering female director Lois Weber as a jack of all trades, Frances began to help Mary with the scenarios for her films. In 1915, Mary cast the beautiful Frances as “the vamp” opposite her sweet ingénue in a film she wrote called A Girl of Yesterday. But Frances had little interest in acting, and began writing her own script for Mary called The Foundling. Mary loved the story, and Frances’s career as a screenwriter was born.

A film poster for the 1915 silent comedy The Girl of Yesterday. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

During the first days of the shoot, Frances was a bundle of nerves. “You needn’t worry over The Foundling,” Mary assured her. “The crew likes it. Always remember that if these men, who are the pillars of integrity in every studio, advise you that you have written a good yarn, then you can relax…the day we started the picture, when they said ‘it’s okay, Mary,’ I knew we were on the right track.”

Tragically, the completed film was lost in a fire a few days before its premier. Mary gently broke the news to a devastated Frances, telling her, “We’ll make another picture together. I can promise you that, and I’ve never failed to keep my word.”

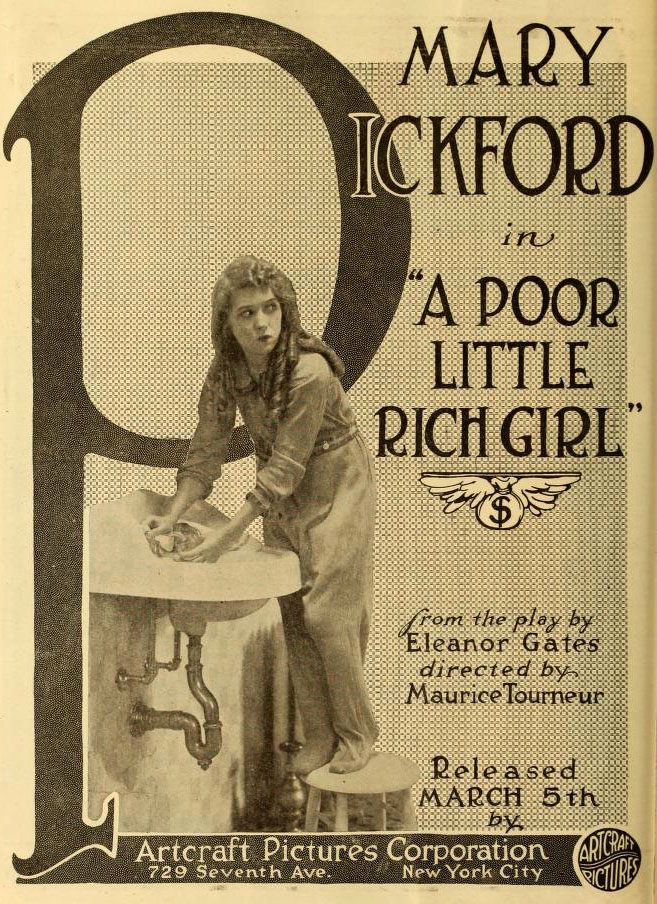

That was a major understatement. The women’s partnership was solidified during the production of 1917’s Poor Little Rich Girl. Based on the saccharine play of the same name, it was adapted for the screen by Frances. “Carried away by our own brand of humor,” Frances recalled, “Mary and I often ganged up on poor serious Mr. Tourneur [the director] and either sweet talked or fast talked him into letting us include some wild comedy scenes which were not in the play or the script.”

One amused co-worker dubbed these simpatico bursts of creativity “Pickford-Marion spontaneous combustion.” The women spent many challenging hours together editing the film, only to have a dreadful screening for a group of all-male executives. The men were appalled by the slapstick humor in the film, as well as convinced it would ruin “little Mary’s” innocent image.

An advertisement for the film Poor Little Rich Girl, written by Frances Marion and starring Mary Pickford, 1917. (Photo: Internet Book Archive/flickr)

The film was given a far-from-grand opening in New York City. Curious to see an audience’s reaction, Frances and Mary snuck into a screening, expecting it to be a disaster. But contrary to the studio suits, the public loved Poor Little Rich Girl. In her excitement, Mary threw off the sunglasses and scarf she had worn as a disguise, exclaiming, “Frances it’s a hit! The biggest hit I’ve ever had!”

“We decided we had learned a good if painful lesson,” Frances remembered. “Although we respected the opinion of the bosses, we realized that a comedy never should be shown without an audience; every day the heads of the studio sat in that vault-like projection room and looked at so many pictures that it was apparent their judgement was no longer dependable.” And thus, the now-commonplace test screening was born.

The huge box office success of Poor Little Rich Girl made Mary and Frances the hottest duo in town. “I climbed back on my high horse,” Mary remembered, “and rode off in all directions.” Frances was put under contract for $50,000 a year, “to prepare special features for Mary Pickford,” at Famous Players-Laskey, a major motion picture company of the silent film era.

They soon formed a happy triumvirate with Mickey Neilan, a fun-loving actor-turned-director. The threesome, all still in their mid-twenties, made a string of hit silent movies together, including Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, A Little Princess, M’Liss, and Stella Maris. For these films, Frances helped redefine the “little Mary” character, making her funnier and smarter. The real Mary, who had spent her childhood being the main breadwinner of her family, loved playing this little girl, and saw it as a way of recapturing the childhood she had lost.

Mary and Frances were so personally connected that Frances ghostwrote “Daily Talks”, a popular newspaper advice column signed in Mary’s name. When Frances joined Mary on a visit to troops stationed in San Diego, she ended up meeting the love of her life, the future cowboy star Fred Thomson. They married in 1919. Mary soon divorced her first husband, Owen, who had introduced her to Frances, and married fellow superstar Douglas Fairbanks. The foursome honeymooned in Europe together, where Frances noticed how Fairbanks bristled at the adoring throngs who chanted for “Mr. and Mrs. Pickford.”

Frances Marion in 1918. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Frances was fiercely protective of her vulnerable friend, while the business savvy Mary constantly tried to curb Frances’s prodigious spending. “Frances if you keep this up, you’ll be on the corner of Hollywood and Vine [Streets] with a tin cup,” Mary admonished her. “If I do, you’ll walk right past me and not put in one thin dime,” Frances replied.

In 1920, Mary and Frances had another hit with Pollyanna, a simpering yarn that they both found “nauseating.” The next year, Frances directed her husband, Fred Thomson, and Mary in The Love Light. Frances had written the story based on her experiences as a journalist on the front lines during World War I. There seems to have been some tension on the set, and even Mary had to admit that the final result was “bad.”

An unfavorable review for The Love Light illustrated the uphill battle Mary and Frances faced as women in Hollywood. “One of the most dramatic scenes in the movie was the destruction of a large fishing sloop off the rocky Monterey coast,” Frances recalled. “It almost caused the death of Nat Daverich, an assistant director. A prominent critic wrote, ‘A man wouldn’t have tried to get away with that phony miniature.’ If only women’s lib had been active in those days!”

The film was a box office disappointment, and after it wrapped, Mary and Frances grew apart professionally. However, they stayed close friends and continued to support each other as women in a male dominated industry. They also championed the careers of other women, including actress ZaSu Pitts. “I owe my greatest success to women,” Frances stated. “Contrary to the assertion that women do all in their power to hinder one another’s progress, I have found that it has always been one of my own sex who has given me a helping hand when I needed it.” Mary echoed this sentiment, telling a fan magazine, “I admire most in the world girls that make their own living. I am proud to be one of them.”

Frances went on to have a storied, Oscar-winning screenwriting career, writing MGM classics like Camille, Dinner at Eight and The Champ. For many years, she was the highest paid screenwriter in Hollywood. In 1928, her beloved husband died of tetanus, leaving her to raise two young sons all alone. After Frances retired from screenwriting, she continued to write books and returned to her first love, painting.

Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks hang a sign at the opening of their studio. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks ruled Hollywood from Pickfair, their estate in Beverly Hills. They founded United Artists with Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith, and starred together in The Taming of the Shrew, with Mary playing the very adult Katherine. In 1933, Mary, exhausted after a lifetime of work, decided to retire. During her career, movie making had evolved from slapdash quickies filmed on the run to giant, feature-length productions filmed in big budget studios. Fittingly, she chose Frances to write her final film, Secrets, which was released in 1933.

Over the ensuing decades, Mary and Frances remained devoted to each other. From the breakdown of Mary’s marriage to Douglas Fairbanks to her remarriage to Charles “Buddy” Rogers, Frances was there, always looking out for the woman she called “Squeebie.” She worried about Mary, who retreated more and more behind the walls of Pickfair, managing her fortune and giving prodigiously to charities. “I miss my career,” she told Frances in a letter. “But I have earned my rest.”

However, alcohol also played a big part in Mary’s retreat, causing her to behave erratically to even her oldest friends. “What business is it of anyone’s?” a feisty Frances said to a reporter. “She gave so much pleasure and that’s all that matters.” The women continued to communicate, though mainly through letters.

Frances Marion died in 1973, and Mary Pickford followed in 1979. In one of her later letters to Mary, Frances reflected on their remarkable run as creative partners and confidantes:

We have arrived at our golden anniversary of friendship. Half a century of love, understanding and companionship…

We’ll go on creating, organizing and fulfilling our destiny until Gabriel toots his horn.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook