The Selenophone, a Short-Lived, Highly Flammable Sound-Recording System

In an exhibit honoring the work of conductor Arturo Toscanini, there’s an odd slice of recording technology.

When Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini was born in 1867, sound recording was a new technology. By the time he died in 1957, the Golden Age of Television was well underway.

A new exhibit at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts is putting audio technologies into context by looking at how a wave of audio advancements affected the life and career of Toscanini. The library has an archive of over 40,000 Toscanini recordings, and has laid many of the significant moments of his life against the timeline of audio technology and preservation. The exhibit, a display of vinyl and 78 records, video, reel-to-reel recordings, letters, and other ephemera, also features examples of exactly what kind of technology the composer would have seen throughout his 89 years.

“We’re working to preserve ‘at risk’ media,” says Jonathan Hiam, the library’s Curator of Music and Recorded Sound. “Formats that are going to be obsolete through technical obsolescence. But we’re also doing intense preservation work on equipment that was never really around a lot to begin with.”

In his lifetime, Toscanini witnessed recording technologies of all sorts: the phonograph, wax cylinders, gramophones, and wire recorders. “You have a really interesting interface of Toscanini with technology,” explains Haim. “He may or may not have had indifference toward technology during his lifetime, but the machinery that surrounded his cultural presence was deeply industrialized. It was literally capitalizing on him and he’s capitalizing on its reach.”

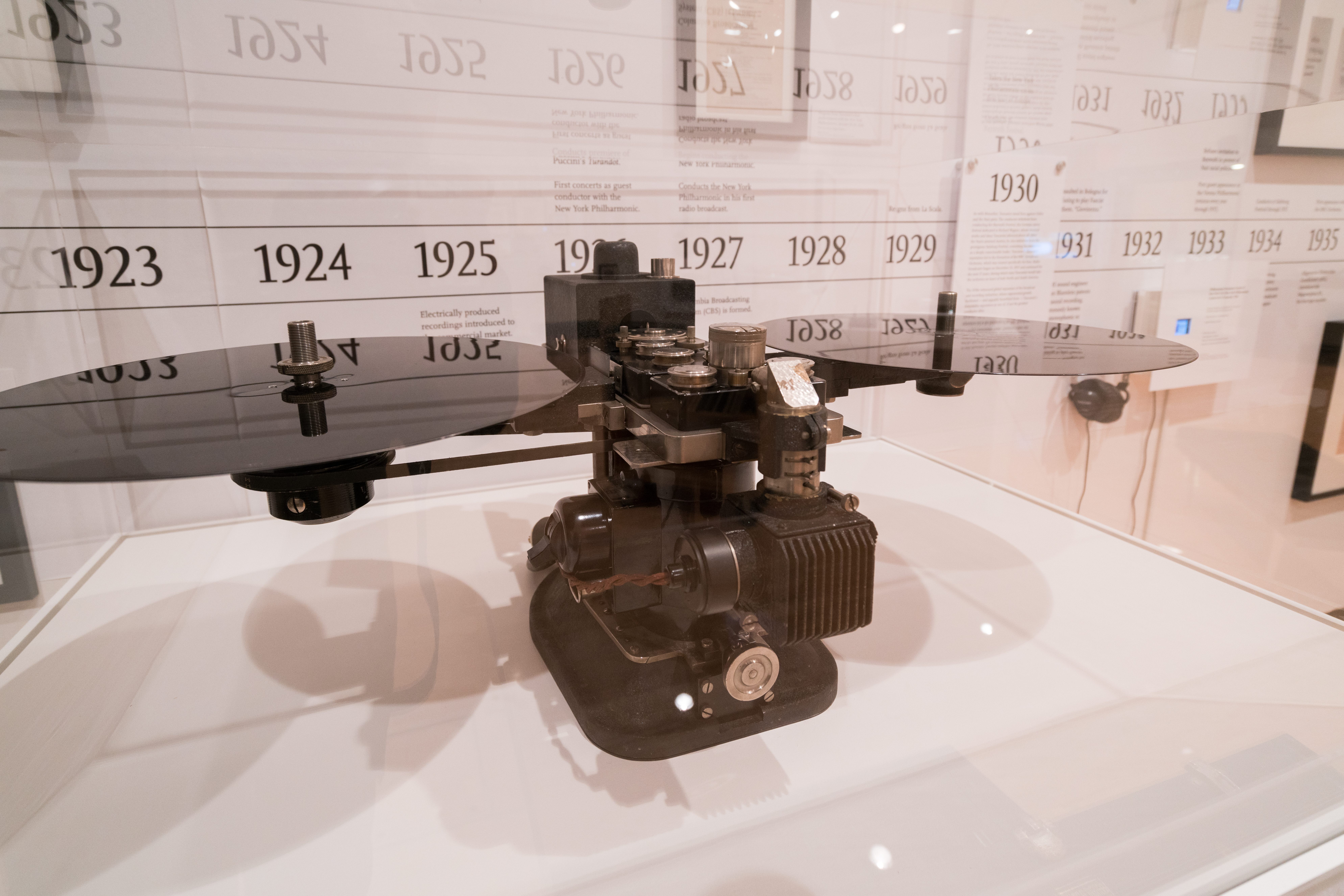

Perhaps the most unusual, and rarest, piece of technology that crossed his path was the Selenophone. This odd slice of recording history was only in use for one year, recorded sound onto 8mm film, and, oh yeah, the finished recordings had the tendency to explode. Nitrate film, the type the Selenophone used, is highly unstable, highly combustible, and any resulting fires are not easy to put out.

The last three of Toscanini’s fully staged operatic performances were recorded on the Selenophone. The device on display at the NYPL, according to Seth Winner, Preservation Sound Engineer for the library, may be the last working one left anywhere.

The Selenophone was developed in 1936 by Oskar Czeija, a Viennese engineer who conceived of the device as a longer-recording replacement for 78 r.p.m. records. “They would essentially burn a signal into [the film] using an optical head,” explains Winner. “It was an attempt at trying to record live performances or speeches than ran longer than 15 minutes. It was essentially one of the first attempts at trying to record something continually.” Czeija, who also ran Radio Verkehrs AG, the first Austrian broadcasting company, not only had the right to broadcast performances, but had full rein to set up his recording equipment at the country’s Salzberg Festival, capturing the Toscanini performances.

Although the Selenophone was a precursor to reel-to-reel tape recorders, it didn’t fare as well in the longevity department; it ceased production after only one year. “It never held on because it was very bulky, cumbersome, and dangerous. It was nitrate based,” says Winner. “Then, of course, what was going on with World War II. He was told to shut everything down, so further development just halted.” The only known recordings from Czeija are from the 1937 Satzberg Festival, and these have been part of the NYPL’s Toscanini archive since the materials were acquired in 1987. Although a transfer from film to archival tape means that they won’t ever have to be played on the Selenophone again.

The NYPL exhibit aims to show that music, and recording history in general, fit into a larger context of world and technology history. Also on display are early attempts at making a record needle (they tried cactus needles, examples of which are also on display), celebrity endorsements for Edison’s phonograph (a signed letter from Tolstoy extolling its virtues), and a telegram to Toscanini applauding his decision to pull out of a music festival in protest of Nazi occupation. The exhibit invites visitors to examine larger movements—in art, in music, in technology, and in historic preservation— through one man’s life and career. “I want people to engage with Toscani’s life and times,” says Hiam. “But I also want people to understand what’s being done to keep these things vibrant and alive.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook