The Efforts to Identify the Lost Souls of America’s Potter’s Fields

From New York’s Hart Island to Dunn County, Wisconsin, experts and volunteers alike work to provide closure to the families of those interred in unmarked graves.

Grave markers constructed by volunteers for the Dunn County potter’s field. (Photo: Bstaab22/CC BY-SA-4.0)

Today, the New York Times has provided a look into the lives and deaths of some of the individuals who have found their final rest at New York City’s Hart Island, one of the few remaining active potter’s fields. The article, which highlights the ways the city has failed to protect the estates and burial wishes of the unclaimed or impoverished dead provides a tragic example of our past and present disregard for the poor and other disadvantaged populations. At the same time, there has also been growing efforts to identify the bodies’ interred in potter’s fields around the country and provide a more peaceful resting place for those who remain there.

Beginning in 2010, medical examiners have used DNA analysis to attempt to identify remains exhumed from Hart Island, according to a 2012 New York Times article. A story in the Tampa Bay Times explains how this practice has helped provide closure for family members of missing individuals such as Ben Maurer, who passed away in Manhattan in 2002. According to the article, at any given time there are 40,000 active missing persons cases in the US, with 25 percent of those cases located in New York. For the Maurer family and others, connecting those cases to John and Jane Does in potter’s fields like Hart Island provides an opportunity for closure.

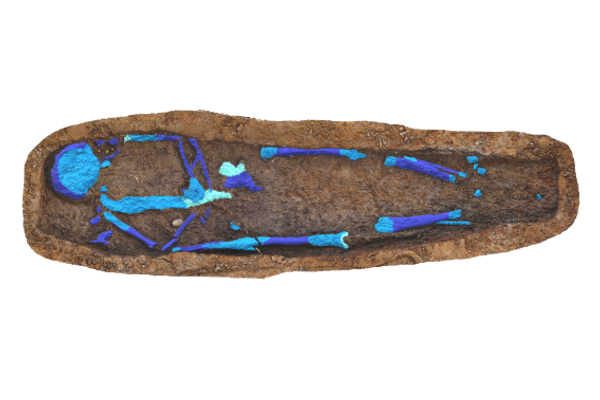

Elsewhere in the U.S., similar identification efforts are underway. In San Bernardino, California, a team of college students led by anthropology professor Craig Goralski and forensic anthropologist Alexis Gray spend their summers working to exhume and identify remains in the potter’s field at the San Bernardino cemetery. The cemetery, which provided a final resting place to over 7,000 destitute or unidentified bodies for 100 years. As with Ben Maurer’s case, the DNA collected from the exhumed remains is entered into a national database, and families looking for vanished relatives must submit a DNA profile to the system to lead to a match. For Goralski, however, the effort is worthwhile; as he explained to the Orange County Register, “If something horrible were to happen to me, I would hate for it to be worse because my family doesn’t know what’s going on.”

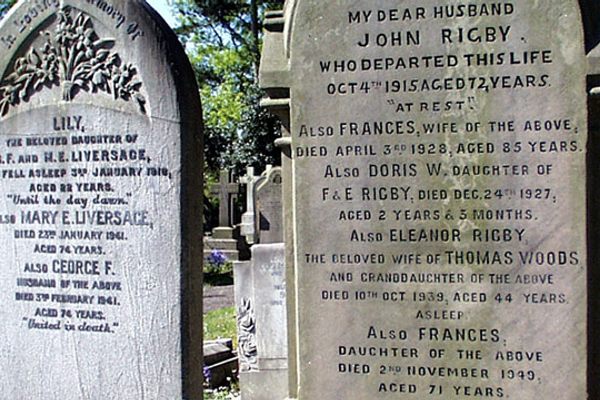

While the DNA database is undoubtedly the best way to positively identify anonymous remains interred in potter’s fields, some individuals have turned to historical research. In Kansas City, Missouri, Georgia Lundy works to uncover grave markers and comb through death certificates to piece together the identities of those buried at the Leeds potter’s field; Lundy’s work was inspired by her discovery that her grandfather had been buried there in 1929. The potter’s field in Dunn County, Wisconsin, is actively maintained by the Friends of Potter’s Field, which seeks to identify as many burials as possible, along with providing grounds-keeping and signage to give the unfortunate souls there an appropriate burial ground.

Ultimately, today’s article in the Times portrays the growing empathy for those who through illness, poverty, or other misfortune found their final rest in the anonymous mass burials of a potter’s field. For Hart Island, this has played out in calls to increase access to the graves, including a proposal to convert Hart Island into a public park as well as efforts like the Hart Island Project, which works to document the burials at Hart’s Island and help family members get access to graves and burial information. Through efforts such as these, the loved ones of even the most disadvantaged among us might find some measure of peace.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook