The Experimental Nuclear Reactor Secretly Built Under the University of Chicago

Chicago Pile-1, the first reactor to reach criticality, was built under a football field.

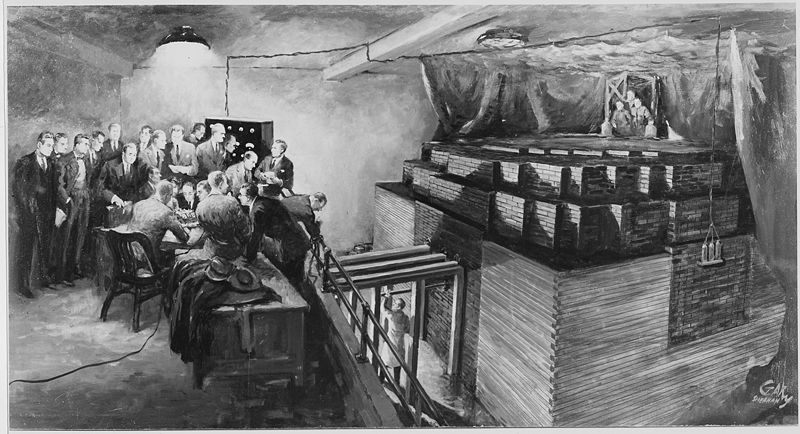

An illustration of the first critical nuclear reaction. (Photo: Gary Sheehan/Public Domain)

On December 2, 1942, the world’s first nuclear reactor was fired up in a subterranean squash court. But instead of a top-secret, sterile laboratory miles from civilization, the reactor went “critical” for the first time in a space directly beneath rows of football field bleachers at the heavily populated University of Chicago campus.

To be clear, going “critical,” in terms of a nuclear reaction, isn’t a bad thing. It is simply the moment at which a nuclear reaction reaches a point at which it reaches a critical mass and starts emitting usable energy, be it as a resource or as a weapon.

The small reactor was built at the University of Chicago as an arm of the infamous Manhattan Project, based in New York. At the head of the project was visionary Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. “He started experimenting with these things at Columbia University,” says Cindy Kelly, President of the Atomic Heritage Foundation. “He realized that the release of atomic energy on a large scale would only be a matter of time.”

Fermi was against the use of atomic energy as a weapon, but felt its use as a powerful energy resource made experimenting with it worth the risk. With his team, Fermi set out to prove that nuclear energy could be harnessed as a clean and self-sustaining form of energy.

Fermi and his team. (Photo: Atomic Heritage Foundation/Used with Permission)

Although there were risks to firing up an experimental nuclear reactor in a densely populated area, Fermi’s team chose to do it underneath the school’s disused football field because they wanted to use student labor to help assemble the atomic reactor. The University of Chicago had discontinued its football program in 1939, and the Stagg Field facilities were not longer in use, but more importantly, the former athletes had a lot more free time as well, and they made for a handy workforce.

Far from the towering smokestacks more commonly associated with atomic energy today, the Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), as it came to be known was monolith made of carefully stacked graphite blocks, interlaced with cubes of uranium. Control rods made of cadmium were inserted to absorb any errant radiation from the reaction. It looked, from the outside, like not much more than a pile of black bricks.

Yet the radiation it produced had the potential to blanket the surrounding area with deadly radiation had anything gone wrong. “It was not a bomb,” says Kelly. “Confusion is commonplace today among people who think that reactors will behave like an atomic bomb and make a big explosion. But that’s not the case. It’s a totally, totally different danger.”

The project was top-secret, and only those who needed to know about it were alerted to the existence of the experimental reactor. Not even the mayor of Chicago was told of the project. “It would only be getting everybody excited,” says Kelly. “They probably figured, they wouldn’t have understood if they’d told him.”

Despite the potential dangers an experimental reactor posed, Fermi, for one, wasn’t that worried. Prior to activating the pile, dozens of tests had been conducted on specific aspects of the reaction, and multiple safety precautions were put in place. In addition to the control rods, the team also kept a bucket of material that they could use to dowse the reactor with, which would immediately put a stop to the reaction.

“[Fermi] was as cool as a cucumber,” says Kelly. “He was completely confident.”

An illustration of Chicago Pile-1. (Photo: Melvin A. Miller/Public Domain)

In the middle of preparing to fire up a potentially hazardous new reactor, Fermi glanced at his watch and nonchalantly sent everyone to lunch, says Kelly. The meal was tense: “At lunch, everyone was thinking about the experiment, but nobody talked about it.”

Afterward, the team returned to the squash court and made history by achieving nuclear criticality for the first time ever. As the reaction gained momentum, creating heat, and throwing off radiation, the scientists, none of whom wore any formal protection, slowly removed the control rods, and measured the amount of radiation the reactor was creating.

Then, when they realized that their experiment had been a success, they replaced the control rods and shut down the reaction. The Atomic Age had begun, not with a bang, but with some careful science. “In Fermi’s words, the event was not spectacular. No fuses burned, no lights flashed,” says Kelly.

After the experiment, Arthur Holly Compton, who had overseen the creation of Chicago Pile-1, reported the achievement to James Conant, chairman of the National Defense Research Committee, using an improvised bit of spy code:

Compton: “Jim, you’ll be interested to know, the Italian navigator has just landed in the new world. The earth is not as large as he had estimated. He arrived at the new world sooner than he expected.”

Conant: “Is that so? Were the natives friendly?”

Compton: “Everyone landed safe and happy.”

CP-1 was dismantled after its successful reaction, and some parts were used in a later reactor, Chicago Pile-2, while other components were simply buried. The jubilant scientists celebrated by splitting a bottle of Chianti, each of them signing it to mark the occasion.

The bottle can still be found in a museum in Argonne, Illinois, but the true legacy of Chicago Pile-1, the daring experiment that took place right underneath an unsuspecting college campus, can be found in nuclear reactors all over the world, and unfortunately, in bombs as well.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook