How a ‘Flying Photographer’ Sees the World From Above

The perspective made George Steinmetz an “accidental environmentalist.”

In 1997, New Jersey–based photographer George Steinmetz decided to learn to fly, when he was assigned to shoot in the central Sahara and learned that his bush pilot had backed out. Steinmetz’s aircraft of choice was not an airplane but a motorized paraglider, which is more or less a backpack-mounted motor connected to a single-seat harness hanging under a parachute-like wing. “I originally got into paragliding because I wanted to fly in the Sahara,” he says, “and where I was in the Sahara you could take off and land almost anywhere, so it was a very safe environment for an unreliable motor.” On his website, the photographer refers to it as his “flying lawn chair,” which let him “fly low and slow over the ground with a minimum of disturbance to people and animals below.” It could also be conveniently disassembled and packed into three bags, weighing less than 50 pounds each. Steinmetz could fly commercial with his own plane in the cargo hold.

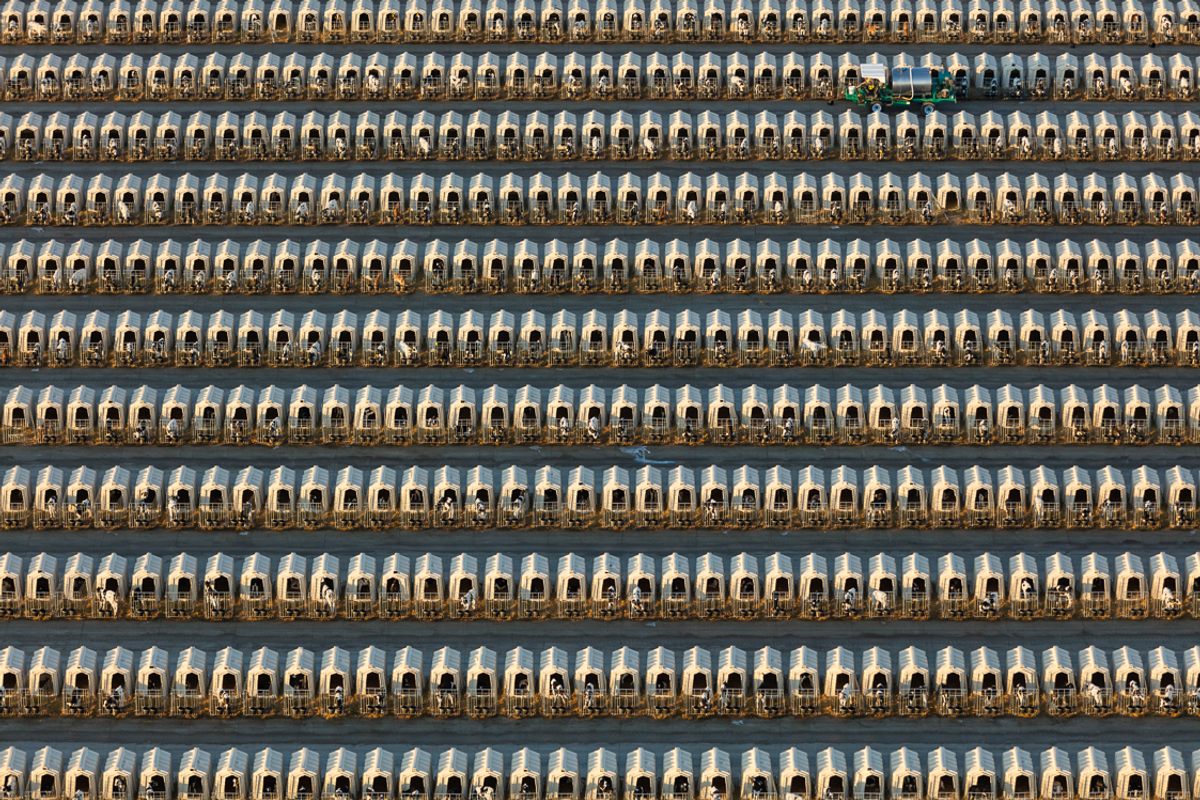

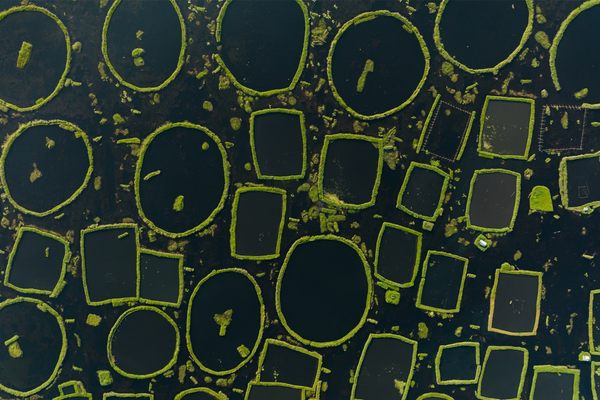

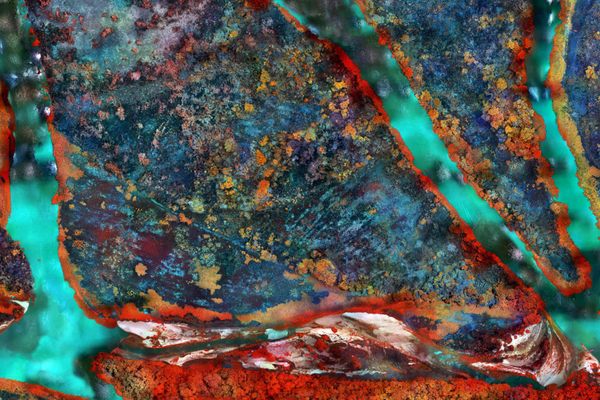

Since then, Steinmetz, now known as the “flying photographer,” has recorded stunning views around the globe which are compiled in a new book, The Human Planet: Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene, published by Abrams Books, with text by science writer Andrew Revkin. With the help of his paraglider, helicopters, and professional-quality drones, Steinmetz reveals not only extraordinary natural wonders, but also the enormous imprint of human activity, from the colorful salt pools of Teguidda-n-Tessoumt, Niger, to the replanting of a palm oil plantation in Sapi, Malaysia, to pandemic burials on New York’s Hart Island. (The latter is not included in the book, and the New York Police Department seized his drone.)

Though the photographer currently shoots almost entirely with drones now because they’re often the best, safest tools for the job, he appreciates the time he spent in the paraglider. “It’s very different, with a drone. Yes, you can get a camera up there,” he says, “but it’s kind of like a periscope in the sky, where you can only see what’s on the screen, you can’t see what’s outside of it.”

Also, he says, “The glider is really quite amazing because you have an unrestricted view, in horizontal and vertical dimensions. Like a motorcycle, everything is out there … Oh! You’re there!”

Steinmetz greatly values that kind of open and direct experience. As he writes in the book, “I consider ground truth paramount, and I need to experience things for myself.” And that experience has been one of change, and how what he’s seen has made him an “accidental environmentalist.” “I’ve witnessed how quickly our population is growing and our wild places are disappearing, and the accelerating rates at which we are consuming the world’s resources … It’s become clear to me that we are entering an era of limits, because we can’t keep consuming resources at today’s pace if we wish to leave a habitable planet to the next generations,” he continues. “The classic narrative of man ‘versus’ nature might need to be rethought, as a narrative of man ‘with’ nature.”

Atlas Obscura has a collection of images from The Human Planet: Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook