The Hot 19th Century Sport That Launched Modern Athletic Betting? Competitive Walking

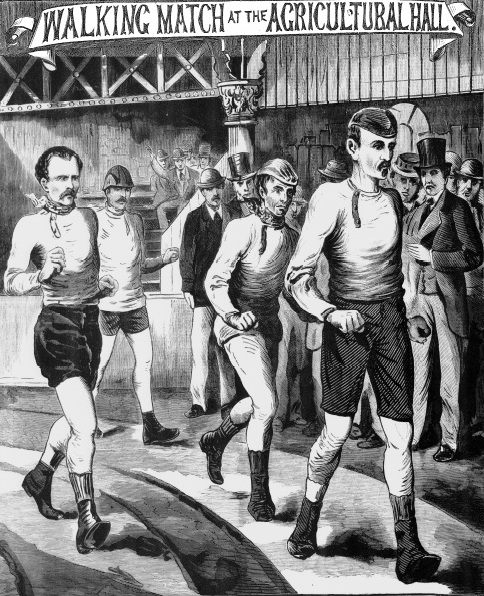

1st Astley International Belt race at the “Aggie”, Islington, London, March, 1878. (Image: Kingofthepeds.com)

If you’re a football fan—or if your coworkers talked you into it—you might have made a small wager on today’s Super Bowl. If your technique for picking a winner was more like flipping a coin than creating a spreadsheet, you can comfort yourself that you are participating in a ritual that has existed for most of human history.

And then you can tell your friends that modern sports betting got started with that least sexy and seemingly un-wagerable of sports—competitive walking.

Evidence for betting and gambling has been found in numerous ancient cultures. The Rig Veda, an ancient Indian religious text, includes the hymn “Gamester’s Lament,” also called “The Gambler’s Lament,” and the plot of the Mahabharata centers around a gambling tournament. Similarly, a few descriptions of betting on chariot races and athletic competitions can be found in ancient Greek and Roman writings. The Aztecs allegedly bet on Ullamaliztli, a ball game, and betting on surfing contests was a “favorite pastime” of indigenous Hawaiians. In American Indian Sports Heritage, Joseph Oxendine describes elaborate betting ceremonies for athletic contests. Examples of sports betting are rife in medieval cultures, including boat racing and foot races in the Middle East, and boxing or wrestling in Europe.

However, sports betting as it’s practiced today did not really come into existence until the 1800s, and it centered around on walking.

Competitive walking, known as pedestrianism, reached the height of its popularity in America and the United Kingdom during the 1870s and ‘80s. According to Liam O’Brien in Don’t Bet the Farm: The Encyclopedia of Betting and Gambling, pedestrianism “had its origins in the English aristocracy who had servants known as footmen whose duties included carrying papers and messages….[T]he aristocrats began to match their footmen against each other in walking contests and [the contests] soon became synonymous with heavy betting.” The contests quickly became popular due to the participants’ feats of endurance; in 1813, Walter Thom published Pedestrianism; Or, an Account of the Performances of Celebrated Pedestrians During the Last and Present Century: With a Full Narrative of Captain Barclay’s Public and Private Matches; and an Essay on Training, which is notable for its rote recitation of various long walks. For example:

In September this year (1812), Jonathan Waring, a Lancashire pedestrian, performed one hundred and thirty-six miles in thirty-four hours, for a wager of one hundred guineas. He started from London to go to Northampton, and return. He went the first fifty-five miles in twelve hours, and half the distance in fourteen hours and a half. After resting an hour and a half, he started on his return, and accomplished the whole distance in three minutes less than the time allowed. He was excessively fatigued.

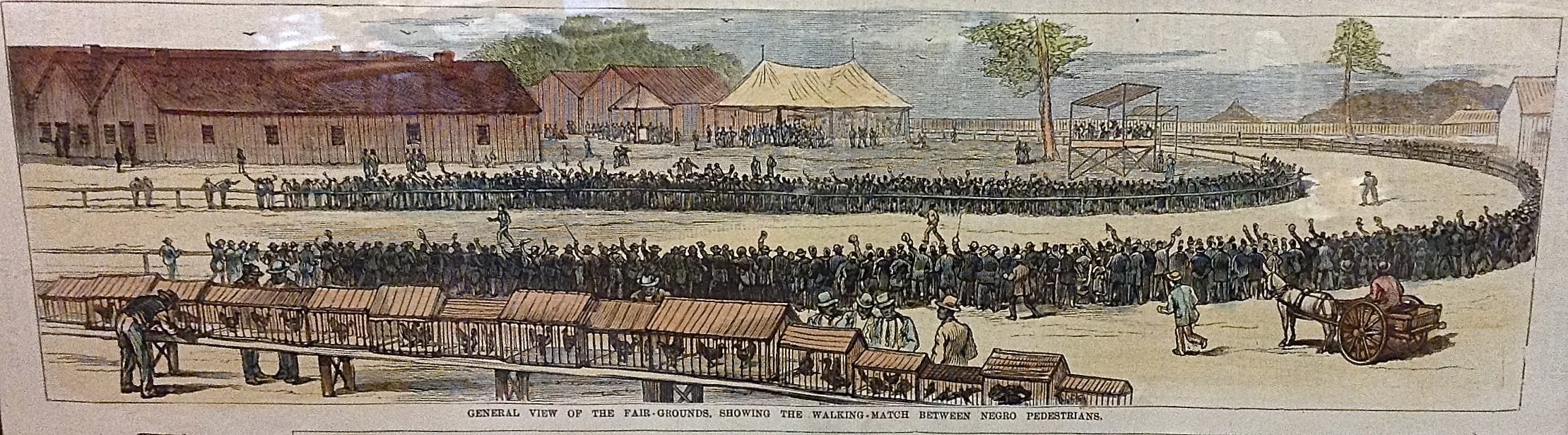

First Grand Fair of the North Carolina Industrial Association, Held at Raleigh, November 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th. From sketches by Joseph Becker. (Image: Wikimedia Commons/Monumenteer2014camper)

The first pedestrian race to fully capture the public’s imagination happened in 1809, when Captain Robert Barclay bet “Bold” James Wedderson-Webster 1,000 guineas that Barclay could walk 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours. The Times estimated at the time that bets totaling £100,000 were placed on the race’s outcome—over £80,000,000 today. By the 1870s, pedestrian races packed stadiums—including the original Madison Square Garden. In 2014, Matthew Algeo—author of Pedestrianism—explained a typical 1870s pedestrian race to NPR. Races could last up to six days, and the participants walked almost continuously: “They’d have little cots set up inside the track where they would nap a total of maybe three hours a day. But generally, for 21 hours a day, they were in motion walking around the track.” To keep their strength up, the racers relied on champagne, which was considered a stimulant at the time. “The problem,” Algeo points out, “was a lot of these guys would drink it by the bottle.”

And for spectators the races weren’t just about watching some guys walk around in circles, as Algeo explains:

There were brass bands playing songs; there were vendors selling pickled eggs and roasted chestnuts. It was a place to be seen. There were a lot of celebrities who attended the matches: James Blaine, the senator from Maine, was a fan. So was future president Chester Arthur. Tom Thumb attended many matches. And so people went to see celebrities and see the spectacle, not just to watch the people walk.

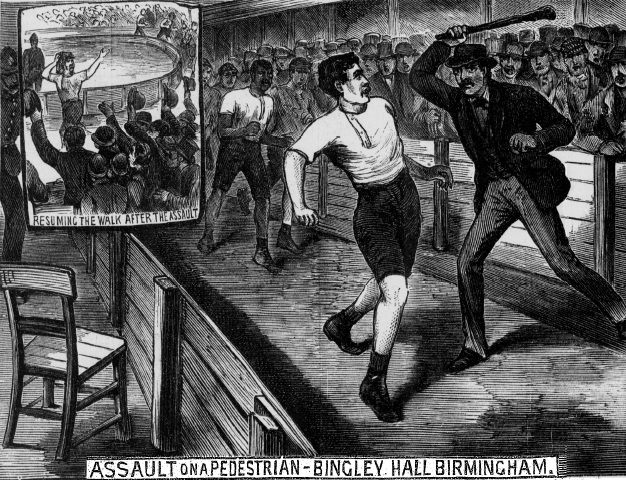

And just like modern-day sports, there was plenty of scandal. Edward Payson Weston, a champion pedestrian, was caught chewing coca leaves 1876, and just like some of today’s athletes, he claimed he used the “performance-enhancing drug” under the advice of his doctor. Because there were so many ways to bet on a race, match-fixing was also an issue. A 1906 edition of Australia’s Sunday Times recounts an incident where racer Billy McDonald was banned from Australian pedestrian races for three months after he was caught throwing a match.

George Cartwright (the “Flying Collier”), gets assaulted by a spectator during the 2nd Astley Challenge Belt (1882) held at the Bingley Hall, Birmingham, England. The assault may have been related to betting. (Image: Kingofthepeds.com)

Although footraces may seem like an odd form of spectator sport, its popularity and amenability to gambling shaped how we bet on sporting events today. And as runners, the 19th century pedestrians put today’s running backs to shame—during today’s three-plus-hour football game, the players will only run about 1.25 miles.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook